SPOILER ALERT: This review contains significant spoilers for Castle of Blood.

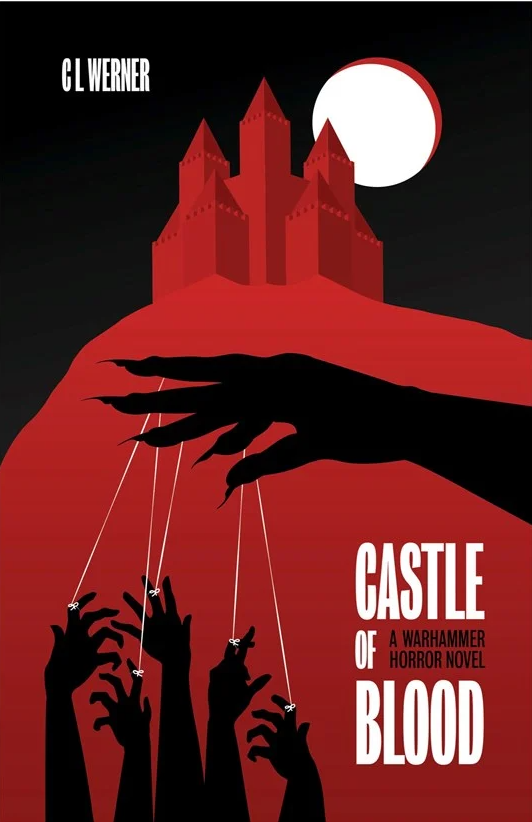

Recently I reviewed the Cursed City prequel novel, a decidedly odd book limited by the circumstances of its existence. Flawed though it is, I enjoyed Werner’s writing in it, and decided to give him another shot with a more typical book with fewer demands placed on it as a piece of marketing – and so here we are, with Castle of Blood, an entry into the Warhammer Horror imprint.

In the prologue we meet Count Wulfsige von Koeterberg, an ageing noble living in the ancient castle of Mhurghast, once a fortress of Chaos before being reclaimed by the Stormcast Eternals and gifted to the von Koeterberg family for their services to Sigmar. The family has lived there for generations as the pre-eminent nobles of Ravensbach, in the realm of Chamon, but now the Count is the last of his line. He is a recluse, shut up in his fortress with his grief – and a deadly thirst for revenge. He has found a way to acquire a knife long held by the Skullcaller tribe – a knife sacred to Khorne, the Blood God, and used to summon the Mardagg, a greater daemon.

Completely unaware of this is a cast of characters from around Ravensbach, invited to join the count at a feast in his castle. They include Magda Hausler, a young swordswoman, her father Ottokar, a renowned swordsmith now driven to drink by a crippling injury, and his wife Inge, who has married below her ambitions and grown to resent her drunken husband. We also meet father and son Bruno and Bernger Walkenhorst, the elder a reformed thief and the younger a burgeoning one, and Baron Roald von Woernhoer, another noble, trapped in a loveless marriage of convenience to Hiltrude with their idiot daughter Liebgarde. Later, at the party, we meet others, including an alchemist, a defrocked priest, an aelven tutor, a duardin cogsmith, and a grasping merchant – and all of their children. Most of these characters are only passingly familiar with each other, though we learn as the novel unfolds that some have much deeper ties, and all knew the Count in their earlier lives. Many of them are surprised to learn he’s still alive; no one has seen him for years, and rumours have spread that he’s long dead and the castle servants are simply pretending he still lives for nefarious reasons of their own.

This turns out not to be the case, but in fact Wulfsige doesn’t last much longer. The Mardagg must be summoned with a blood sacrifice, and as far as the Count is concerned there’s no better sacrifice than himself, a man on death’s door who has only lived as long as this to enact his cruel, calculated revenge plot. Each of the parents was acquainted with his son Hagen, and in some way or another helped bring about his ruin and suicide; now Wulfsige intends to bring about their destruction in turn, by turning their children into vessels for the murderous daemon.

It’s a bold set-up, which leads to a riot of mayhem and violence as the Mardagg fulfils its purpose. Adding to the mix is the local Grand Lector, who besieges the castle to prevent the corruption spreading, and Klueger, a witch hunter and Magda’s lover who arrives to offer what help he can – with devastating consequences.

Coming in at a little under 200 pages, this is a brief entry into the Warhammer Horror canon, but it’s good fun, full of twists and turns and confessions of guilt that heighten the tension and spread the conflict around. Some of the characters are stereotypical in the extreme, particularly the non-humans – the duardin is stubborn and stands on his oath even in the face of death, the aelf is haughty and superior, you know the drill – but the ones we spend most time with have more going on. The Hauslers in particular stand out on the page, a family gravitating around a constantly-boiling three-sided conflict, which spills over to the Walkenhorsts and to Klueger, while the von Woernhoers clash with icy savagery, with Roald haughty and proud of his lineage – except that it’s not his lineage, as von Woernhoer is his wife’s family, a fact of which Hiltrude is quick to remind him when he attempts to flaunt his nobility and breeding to the others.

The novel does have its limitations. With the characters’ freedom of action circumscribed by the divine terror of the Mardagg on the one hand and the more pedestrian threat of crossbows and spears from the Ravensbach militia on the other, there is perhaps too little for them to really try and do to escape their fate, which places an over-reliance on the possibility of an escape via a secret passage filled with traps which gets revisited repeatedly, with a bit of a feeling that someone has written a module for their DnD campaign (well, I guess Soulbound) and really wants to tell you all the clever devices they’ve filled it with. This is compounded by the novel not quite being one thing or the other. This kind of premise typically is either a) a murder mystery with an unrevealed killer slowly picking off characters, or b) a ghost story with the characters attacked at random by a supernatural power they struggle to confront. The former, of course, is right out, as we know within the first 50 pages exactly what’s happening. The latter is a bit closer to what’s on offer, but apart from one early attempt to exploit the (sadly long-dissipated) sanctity of a Sigmarite chapel, the characters never do anything remotely effective to combat the daemon – even the witch hunter, who talks a big game but has no ideas more creative than “hit with sword” or “shoot with pistol” until near the conclusion, when he adds “trap in a pentagram” before returning to “hit with sword.”

To some extent this is because the daemon isn’t actually the focus; instead we’re building to a conclusion centred on Magda, with the bloodshed in the name of revenge creating a new cycle of violence – all to the good as far as the god of blood and skulls is concerned. Her character is probably the most effectively-drawn in the book, and her arc, beginning with the aforementioned familial strife, is the real story here. It’s effective, too, with a couple of nice twists that lead to a very Warhammer denouement and spin on the “final girl”; it’s just a shame that getting there can end up feeling a bit rote, as we go through the motions of the other characters messily dying with clockwork inevitability.

Ultimately, this is a short novel with that clips along at a decent pace, and the highs of its best moments outweigh the somewhat exposed grinding of its narrative gears as we’re moved from set piece to set piece. If you’re at all interested in Warhammer Horror, or just a fan of the Mortal Realms in general, you’ll have fun with it – and for Black Library, that’s what counts.