In our How to Paint Everything series, we take a look at how to paint different models, armies, and materials, and different approaches to painting them. In this article, we’re exploring how to paint leather.

Whether you’re in the fantastical realms of the Age of Sigmar or walking the battle-ravaged wastelands of the 40k universe, there’s a good chance you’re going to come across the opportunity to paint something made out of leather. From straps to bandoliers to boots and gloves to holsters, this flexible hide material is used to create a variety of important clothing items and accessories, and today we’re covering everything you need to know about the material and how to paint it.

An Introduction to Leather

Leather is, in the broadest terms, the skin of an animal that has been processed and treated so that it doesn’t rot. To do this, you get rid of all the junk you don’t want, like flesh and hair, apply a chemical treatment to stabilize the protein, then remove most of the water from the skin, which also helps prevent rotting. Afterwards you apply any dyes to the leather, and saturate it with stable oils to make it flexible again, and prevent it from reabsorbing water instead.

Undyed leather is typically a pale bone color without any oils applied to it to. Once oils are applied it darkens slightly to a somewhat pale tan, and as it ages and is continually conditioned, turns a warm, rich orange.

A treated cowhide is very thick, sometimes several centimeters for an adult cow. The top portion is dense and smooth, while below it is a large amount of fuzzier, less dense material. For most things, the leather is split into a top portion, which is what we’d normally recognize as leather, and the bottom, which is suede.

For the most part, in this article we’ll be talking about the top portion of this leather. Suede is not a particularly good material for stomping about the battlefields of the 41st millennium. It reacts poorly to mud and water and is typically found in more civilian applications.

Mechanisms of Aging

We know what leather is, so let’s use some of that information to take a look at how it acts. Unlike metal, plastic, or fabric, leather is a natural material, and as it ages, is impacted in a lot of different ways by its environment and what is done to it. Let’s go over these ways, roughly in order of how big of an impact they will make at 28mm scale.

Credit: Evan “Felime” Siefring

- Abrasion: Like all materials, leather is damaged by rubbing against rough surfaces. As a general rule, scuffs will make leather lighter. This can just be a slightly lighter version of the base color, or, in the case of dyed leather where the dye hasn’t penetrated all the way through, as the leather is abraded, more and more of the natural leather will be exposed, resulting in brown, or even orange highlights in areas of high wear.

- Conditioning: To stay resilient and pliable, leather needs to regularly have oil or something similar applied to it to prevent it from drying out. Over time, this slowly darkens the leather until it turns the warm orangish color if undyed, or darkens less dramatically, if dyed a light color. Dark leather tends to show very little of this. Another, arguably more useful to you, side effect of this conditioning is that old abrasions and scuffs get rubbed down and darkened, making them slowly fade compared to newer scratches.

- Staining: Leather is porous and absorbent. Especially if not conditioned well, it will greedily soak up water or oil that gets on it. Oil stains will typically result in a darker spots, while water stains are more interesting. Water, especially dirty puddles with all sorts of gross stuff in them, will act a lot like unevenly applied washes, and form darker tide marks on the leather around the edge of the stain.

- Burnishing: We’re getting into some real nitty gritty stuff you can probably skip here. While rubbing against rough surfaces will scuff and make leather lighter, rubbing against smooth surfaces actually does the opposite, both through heat and transfer of pigments into the leather. Typically you see this on areas that are constantly rubbing against soft materials like fabric, like the inside of a sling back or rifle strap. On old, light colored footwear that is very well taken care of, continual polishing of the toe and heel can also darken the leather. (This patina is also commonly imitated using pigments or fire.)

Credit: Evan “Felime” Siefring

I’m painting tiny army men, how does this help me?

That’s a whole lot of information. Let’s cut to the chase and start looking at some ways all that knowledge can inform your painting choices.

- Highlight Colors: The first thing we can take away from all that is that leather is our color choice for highlights. As leather abrades it will expose areas where less dye has penetrated. In areas of high wear, working brown or even orange into your highlights gives your leather a lot of richness and a lived in feeling.

- Highlight Texture: As a portion of your highlights are coming from scratches and scrapes in the leather, how you highlight will have an impact on how worn the leather looks. Smooth highlights will look newer and well cared for, while dotting and interrupting your highlights will make your leather look a lot more battered and worn.

- Layers: Over time, especially if well cared for, scrapes and scratches on leather will fade. By layering washes and glazes over scrapes, then adding new ones on top, you can give your leather a lot of history. The simplest and easiest way to go about this is to paint on faint scrapes before you apply a wash to add shading, then highlight with more scrapes afterwards. Working with layers and glazes also has the convenient side effect that if you take your highlights too far or don’t like how something is turning out, you can just run over it with a wash of Nuln oil or Agrax Earthshade and work back up to somewhere you’re happy with, without redoing the entire process.

Different Types of Leather

There are a lot of different types of leather, so let’s go over a few, and how they might impact how you paint them.

Credit: Evan “Felime” Siefring

- Different Dying Processes: Traditional leather dye tends to penetrate fairly shallowly into the leather. However, some modern processes can penetrate much deeper. In these cases it’s important to think about where your leather comes from when choosing how to highlight it. Leather from a feudal world or a workshop somewhere in the mortal realms will almost certainly fade to a natural brown or orange, while leather dyed in a vat on necromunda or in a factory churning out untold numbers of boots a day for the imperial guard will likely show much less brown and orange, with only hints of brown in the highlights.

- Treated Leather (and Synthetic Leather): Cheap leather is often made from animals that have been getting caught on barbed wire in farms and otherwise accumulating scars for their entire lives. To achieve a uniform surface, the leather is sanded down slightly, and some sort of plastic is adhered to the top, with a fake grain. This process can also be performed on fabric or suede, resulting in Synthetic Leather and very cheap leather respectively. In the very worst case, this can be done to little scraps of leather shredded up and glued together, to produce something which they can technically say is leather to sell it to you. All of these things are going to look roughly the same at a tabletop scale. Treated leather does not scuff easily, and will not show any natural leather color through. As it’s essentially plastic, you should highlight it with lighter versions of the base color, and not to brown or orange. When it does scuff, the outer layer is ripped off, ending up with something I would paint fairly similarly to a paint chip, with a light highlight underneath of a patch slightly lighter than the base leather color, though with a much more ragged texture than chipped paint.

- Tooled/Carved Leather: If you’re painting models toting intricately carved and engraved leather, great. The process of beating down the leather into these patterns darkens it, and dye is frequently rubbed into the recesses to enhance them. Wash those carvings with Agrax Earthshade and keep on trucking!

- Textured Leather: This comes in two types. Sculpted texture on your model, such as dark elves with scaled lizard hides draped over them, which I’d handle with a wash and subtle highlights to pick out the edges of the scales, and really tiny textures, such as pressed pebble grain leather or exotic leather like alligators or lizards. Frankly, these are not going to show up from a few feet away on a 28mm scale miniature. If you are painting something like this, I would suggest looking at pictures of what you’re trying to emulate, painting in the texture, then doing the rest of the leather highlights and shades with glazes, before going in to touch your freehand texture back up.

- Suede and Roughout Leather: Suede, as we discussed, is the interior fibrous portion of leather. It is rarely used in any military setting. However, roughout leather sometimes is. Roughout leather is normal leather, containing the strongest upper portion of the leather, but with the inner, rough portion on the outside. Unless carefully maintained, it doesn’t handle water amazingly, but is almost impervious to scuffing, and is commonly found on desert combat boots. To portray either of these, you’ll want to paint your base color then highlight very smoothly up almost to white, keeping things very matte. The loose fibers catch the light and diffuse it in all directions, much like if you were painting velvet. Most scuffs will be a light color, as fibers are lifted up, but if they are instead smoothed down, scrapes can be darker instead. Suede will not burnish or scuff to a different color, but scuffs will fade over time as they get smoothed back down. The final consideration is stains. Suede picks up stains easily, and any portion that is frequently rubbing against anything dirty will acquire faint greyish patches as dirt is worked into the material.

Credit: Evan “Felime” Siefring

Credit: Evan “Felime” Siefring

Painting Leather

Depending on what you’re going for, there are a few ways to tackle painting leather on miniatures.

Felime – A Whole Load of Leather

Before we go into step by step detail on exact methods, I’m going to use the test model I did for this article to show off a variety of different leather textures and colors, and broadly discuss the techniques used for each.

This is one of Garrek’s Reavers from Warhammer Underworlds. I decided to go with three distinct types of leather on this model, Light Brown, Brown, and Black. When you’re painting a model that has this much leather on it, it’s important to separate the areas using different colors and textures. Otherwise you can end up with a model that is just a confusing sea of brown.

- Light Brown(Pants, Weapon Wraps, Bracer): The pants are a base of Gorthor Brown, with scratches and highlights added with a mix of Gorthor Brown and Jokaero Orange. The entire surface was then washed with Agrax Earthshade, and more scratches were layered on with the mix, and finally pure Jokaero Orange. The weapon wraps and bracer are the same recipe. However, with the straps across the bracer, instead of painting an entirely different color, I just stopped after the Agrax Earthshade wash, and didn’t add any further Jokaero Orange, to keep them slightly distinct fromt he leather surrounding his forearm.

- Dark Brown(Boots, Pouch): VMA Burnt Umber (Slighly transparent, so make sure to do two thin coats with this color) highlighted with Gorthor Brown, Washed with Agrax Earthshade, then highlighted back up with Gorthor Brown, and finally Gorthor Brown with a very small amount of a bone color mixed in. I kept these highlights fairly smooth. Large scratches don’t work quite as well on very small areas like boots, and I wanted to keep them texturally distinct from the more weathered pants.

- Black Leather(Belt, Greave Straps): The black leather starts from a base of VMC Black, highlighted with a mix of black and Skavenblight Dinge, then washed with Nuln Oil. Afterwards, I highlight back up to Skavenblight Dinge, mixing in a little bit of Gorthor Brown for an edge highlight, and finally, just a little bit of Jokaero Orange mixed in for the extreme highlights. I was very sparing with the Orange, keeping it mainly to a few edges and the tip of the belt. Below, we go into some more detail on painting some black leather using the same process.

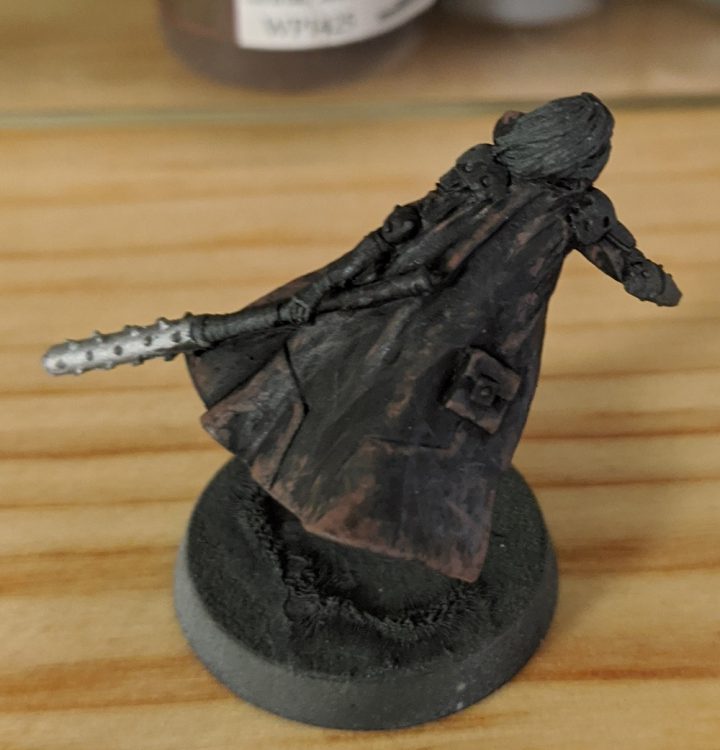

Felime – Black Leather Coat

Now let’s take a look at some of these techniques in far greater detail. For this exercise, I’m going to paint a long black leather coat. In the first portion, I’ll demonstrate a lot of the techniques for scratching and roughing up leather convincingly, then add some staining along the bottom for a bit of flair. As I will be mixing back and forth using a lot of the same colors, and using very thin paints, so a wet palette is very helpful if you’re following along. Otherwise, you can see the paints I’ve used in the picture below.

First, toss down your black basecoat, I prefer VMC Black. Then add in some highlights I did a few layers, first with a mix of black and Skavenblight Dinge, then with more grey, then with pure Skavenblight Dinge. I follow the areas that would typically be highlighted, then work in the grey to high wear areas as well. The edged of the coat, pockets, etc. You do not have to be particularly precise at this stage of painting. You’re mostly sketching in initial highlights right now.

Now, mix in a little bit of your Gorthor Brown into the Skavenblight Dinge, and add some scratches and highlights using this color, before finally using pure Gorthor Brown. With the pure Gorthor brown, focus mainly on areas that would see a lot of wear, rather than just highlighting with it. I also emphasized the seams slightly using these colors.

Now just hit the entire coat with a wash of Nuln Oil. This will even out your messy, scratchy highlights a little bit, dull them down so you can add more layers on top of them, and form the main shade for the leather.

Your highlights have now been dulled down a bit. Now add some new ones on top using Skavenblight Dinge, Gorthor Brown mix, and mixes of the two. You’re roughly repeating your earlier steps at this point.

Now, it’s time to get a little frisky and colorful! Add some Jokaero Orange to the Gorthor Brown and add some more scratches, focusing even further towards areas of high wear, and finally pure Jokaero Orange to highlight the most worn edges.

At this point, you could stop if you don’t want to add any staining. You’ve got a heavily worn coat that has been through years of battles. If you do want to add staining, first paint along the bottom of the coat using Nuln Oil, leaving a ragged splotchy edge where the coat has been dragged through mud or water.

This has tinted the bottom edge, but it isn’t all that defined. Once the Nuln Oil is dry, follow along the top edge to define your splatter pattern using either Skavenblight Dinge, or Skavenblight Dinge mixed with Black. You can also now make the splatter a bit more detailed and intricate than you could just using Nuln Oil.

At this point, it looks like the coat is wet. To turn this into a stain, take some of the same paints you used to define the upper edge, and glaze below your stain, leaving a slightly faded, feathered edge up to the darkest edge of the stain. I would recommend doing this in a stage or two, so you get a gentle fade rather than an abrupt line.

At this point the stain is done. All we have left to do is bring back the highlights and scratches we glazed over with grey. Using Gorthor Brown and Jokaero Orange, quickly bring back the color and brightness of your edges and scratches. As you’ve already got a guide in place and most of the work done, this last step goes quite quickly.

And you have your finished coat, ready to see more wear and tear on the battlefield. Most of my leather follows a very similar process, just using different colors and to different intensities.

Felime – Burnishing

We’ve taken a look at abrasion and staining explicitly, and incorporated some elements of conditioning through the fading and layers of scratches. Burnishing isn’t something you’ll be using often on 40k models. Most places that are constantly rubbing against soft surfaces, such the side of a leather bag pressed against the body, are hidden because they’re pressed up against those soft surfaces. Old leather shoes can also become burnished on the toe and heel from years of polishing. However, you won’t see this often on soldiers. Light leather, where it will be most visible, isn’t popular for military footwear as it shows stains easily and is harder to maintain. The toes and heels of combat boots are also constantly getting beaten up, so abrasion will typically wipe out any burnishing that appears. That said, if you’re painting a rogue trader, high commander, or other imperial noble, you might want to incorporate burnishing, as it can be quite pretty. Because of how pretty it can be, it’s often emulated using dyes on dress shoes, rather than waiting for years of wear and polishing to do their magic.

To follow along, you will need the following paints:

We’re going to go for a light colored leather, so we’re going to start with a base of Jokaero Orange. It’s going to look really orange, because you just painted it orange, but the further steps will tone this down a bit.

Pure Agrax Earthshade is going to be a little bit too strong for our purposes, so mix it with Lahmian Medium on a (non wet) palette. Roughly a one to one ratio will do well. Then wash the Jokaero Orange.

Now take VMA Burnt Umber and water it down quite a bit, and gently glaze over the toe. Burnt Umber is a fairly transparent paint, so it works exceptionally for this. You’ll want to do 2 or 3 coats to work up a nice fade. You may have to work some Jokaero Orange back into the edges to smooth it out and fine tune the shape, but luckily Jokaero Orange also thins down into a glaze quite well. If you’re comfortable we blending this is also a place it works quite well.

Felime – Leather Toolkit

If you’ve been reading closely, you’ve probably noticed that the same paints tend to come up again and again. I find that I keep coming back to the same paints for their versatility and how useful they are for leather. As a conclusion, I’d like to quickly go over these paints, and why I like them, so that you can look at the paints you have, and see if any fit the bill before buying extra paint.

- Vallejo Model Color Black: This is just a very nice black that goes on matte, covers well, is fairly neutral and thus mixes well, and is all around excellent.

- Vallejo Model Air Burnt Umber: It’s a great dark leather basecoat, and it also doubles as an excellent glaze.

- Skavenblight Dinge: Skavenblight Dinge is an excellent grey. It is dark and is ever so slightly brownish, making it perfect for leather. It also thins well and can go on slightly transparent.

- Gorthor Brown: A medium brown that is slightly desaturated (grey-ish). This makes it work great mixed in as a highlight for black, or as a base for other leather. It also thins well and can be put on slightly transparent.

- Jokaero Orange: It’s orange, it’s slightly pale, and it’s slightly transparent. All excellent attributes for painting leather. You’ll notice that all of these paints thin well. This is important for painting subtle highlights using glazes, and so that instead of mixing a dozen different colors, you can use glazes of different intensities to achieve the same effect more quickly.

- Agrax Earthshade and Nuln Oil: Let’s be honest, you own these already and may have spilled at least one of them all over your carpet. They’re great washes for brown and black, and can be used to shift the color of the leather you’re painting easily.

- Honorable Mention – Lahmian Medium: Not pictured, but if you haven’t tried Lahmian Medium, it’s great. It waters down washes butter smooth, and is excellent for making very transparent glazes.

- Honorable Mention – Flesh Tones: Not pictured. Flesh tones are another excellent paint to look at for painting scratches in leather. Because they tend to be so much lighter than the base color, you have to paint them in very thin, controlled scratches, lines, and highlights. While laborious, this can look amazing, especially combined with glazes.

Look Good in Leather

That wraps up our look at painting leather. Hopefully you have everything you need now to tackle different types of leather, materials, and ages. As always, if you have any questions or feedback, or want to share photos of your own techniques, drop a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.