I feel like most of these articles have followed the same basic pattern:

- Have idea

- Do idea

- Realise I was wrong about idea on some level

But not this time! Well, not to the same extent anyway, because I really feel like I’ve got somewhere, with just about enough knowledge to actually understand what I’m doing, and then backed it up by dragging my partner and friends around Paris showing that off. On top of that, I think I’ve made a decent, informed decision about miniature scales and the kind of games (and modelling projects) I want to take on in the future, so before my painting table drowns in womble marines I’m going to give myself a few moments of smug satisfaction.

Ok, I enjoyed that. Back to making mistakes.

Where are we?

It’s worth checking in how far I’ve got on this road to Austerlitz, because I said I’d do that when I completed a unit all the way back in episode 4. It’s also, astonishingly, been 6 months since this all began for me, so probably about time to see how far along I am on this ill-thought-through attempt to learn, and play, Napoleonics. I set out to achieve a couple of things:

- Learn about the Imperial Guard

- Paint a shedload of 28mm Napoleonics and dabble in some other scales

- Do some conversions to fit line infantry into the Guard mould

- Play some different rule systems

- Find out about the Napoleonic wars

Reflecting on all that six months on, I feel pretty damn good about my progress. Picking up some old Ospreys on the Imperial Guard and reading them in the bath (a good place to make important decisions on uniform shades) got me more or less sorted on number 1, to the point I can hold my own in the groggiest discussion. I have read an absolute units worth of Napoleonic material, and am at the point now where a new biography or history has me mentally comparing the scholarship instead of trying to work out what they’re saying, which is a good milestone, ticking off point 5. I’ve definitely played some different rule systems, falling head over heels for Sharp Practice (like everyone else in the goonhammer historicals crew), enjoying a bit of Black Powder and – most excitingly – trying out a new game we’re going to review soon!

But have I painted a shedload? Well, I’ve got 60 Old Guard Chasseurs, 40 Middle Guard Velites and 30 Young Guard Tirailleur-Grenadiers, accompanied by 8 Flanquer-Chasseurs, a sprinkling of officers and the big lads on horseback. The infantry now completely fills a really useful box. I’m happy with my progress, but is it really enough? No. No it isn’t. I want my troops to shake the table when I put them down. I want to be the guy who in a multiplayer all day battle says sure of course you can borrow some units, take one of these boxes of 100 men. I want the Goonhammer editors to check in on me at the end of the year because they haven’t heard anything and it turns out I’ve been crushed under the weight of clipped off sprues. I want something I can be monstrously, inappropriately proud of.

I want a thousand men.

Questions of Scale

My aim with my 28mm force is another two infantry battalions and two more horse, with some guns, by the end of the year. That’s actually pretty easy, one is half painted on my table at the moment, and the guns will be quick. If I’m going to field a thousand men though, I’m not going to do it at 28mm alone. I’ve never really played with other scales of miniatures – I’ve come to wargaming through the carefully bounded Games Workshop ecosystem – but now is the time to branch out, to think big by going small. Over the last few months I’ve been buying miniatures at a couple of scales to try out something different, and am working towards making the big decision – which scale to pick for the really big battles?

15mm-ish

One of these purchases was the Warlord Games Epic Waterloo sprue, via Wargames Illustrated. These are French line infantry in their post 1812 uniforms. The sculpting is really nicely done, every man is attached to the same strip but is distinct, details are crisp, there’s good variety of poses and uniform details within each group of ten, and they take paint well. the range is growing and looks like it will be supported well enough to at least make buying and painting a force worthwhile.

For all that, I absolutely hated painting them. They’re detailed enough to want, and large enough to demand, more or less exactly the amount of time and effort involved in painting 28mm. You could do the buttons on each man, each face has enough detail (even at 3mm long), that you really want to pick out features with another round of highlighting and the cross belts are raised just enough that you want to layer and shade. Unfortunately, they don’t have the prominent raised detail that 28mm has, so I found it difficult to pick out details using quick timesaver techniques. Painting one ten man strip was fun, painting two was a drag. I cannot imagine painting 100 of them to get to the thousand men mark. I’ll use the minis for dioramas at some point, but until then into the bits box they go.

3mm

Genuinely didn’t know people made miniatures this size. Turns out not only do quite a few people make 3mm miniatures, one guy Oddzial Osmy makes beautiful, genuinely breathtakingly fantastic, miniatures in 3mm. They’re tiny, they’re impossibly well sculpted, they have fantastic detail, beautiful casting and in a massive range of historical eras. The Napoleonics are honestly stunning, identifiable as their units – grenadiers, line, command, skirmishers, etc, in the right hats and uniforms, absolutely everything you could want.

I bought a couple of test packs (for not very much, they’re so tiny), and absolutely devoured the modelling, painting and basing process. Going for 70 men – a section, as I found out in part 5 – per base, with enough room for skirmishers out front and some small terrain pieces, the whole process was a delight. 3mm means simple block colours – particularly bright colours – stand out better than washed and highlighted layers, so light blue drybrushes, black and purple inks and pure white were the way to go. I cranked out a couple of line regiments as Middle and Young Guard, and added a column of Flanquer-Chasseurs in their green and yellow.

Even the basing is really good fun, using my standard flock, static grass, texture paint and clump foliage in new ways to create a whole environment of paths, bushes, trees and streams. I can imagine really going to town on how bases would join up with each other, forming up a line of battle and telling that story through the basing materials. Already, the Middle Guard sections stand together in their companies, the Flanquers are in column marching up a road, ready to provide the targeted fire their 28mm comrades have been practicing in Sharp Practice, to relieve pressure on a threatened square. Lots of scope to play around with, and the base sizes give me a good replacement for cards in Blucher.

I haven’t gone all in on these yet though, because of an old adage learned through twenty long years of service on the gaming front: the best games are the ones you have opponents for. At the moment I haven’t got anyone else to play with in 3mm Napoleonics. If you’re a member of the HATE club reading this though, consider that your warning that I’m about to get real evangelical about this scale.

6mm

6mm is a common scale for Napoleonics, supported by another Goonhammer favourite Baccus. A couple of test purchases have arrived on my desk recently, so please excuse the unpainted tin! As a scale, its a very nice halfway house between the not-really-small 15mm and the preposterously tiny 3mm, balancing small size with an actually enjoyable amount of detail. These were my first Baccus minis and the hype is worth it – crisp detail, clear variation in poses and uniforms within each strip and easy to clean and prepare.

I picked up a line unit and *gasp* Spanish guerrillas, to form a few sections of slightly less regular Napoleonic French for a Haitian army under Toussaint Louverture. I’ve been wanting to do something on Haiti for a while, and I think this scale gives an interesting difference from my Guard French, and opens up a lot of different modelling and painting opportunities. Finding 28mm Haitian miniatures is difficult, though Trent Miniatures (now sold by Skytrex) did make a fantastic range. The other options get too piratey, or don’t reflect the organisational nous, tactical and strategic that Toussaint had and used for and against the French. 6mm lets me skip over some of the detail that isn’t reflected in 28mm miniatures, and also lets me play games with more of the bold redeployment and lightning quick marches of the greatest of the Napoleonic Generals.

6mm is also the game played at my club, so basing and unit sizes are consistent and decided. There’s also a range of terrain in the stores already that works at the scale, so games are possible without cajoling people to buy into a new scale en masse. That, and the detail, range options and just overall pleasant feel of 6mm has decided it as the second scale for this project, so going forward expect updates on my Large Guard and my Smaller, infinitely more bad-ass, Haitian army.

1000 men minus 22

With the 20 15mm guys, the 280 3mm and the 100 6mm on the painting table, that thousand men doesn’t seem too far off. There’s still 28mm to paint though

One of my Large Guard units didn’t get the intro it deserves when I finished painting it, and this really should be addressed. With a mass of plastic infantry still languishing on my painting queue, I needed another unit that would use up all the greatcoat models, accept a number of different manufacturer plastics that I’d bought by the sprue (Perry, Warlord and Victrix), a couple of metals from Front Rank, and be exceptionally quick to paint to get over the hump of the 5th 22 man unit. Step forth, hastily mustered Young Guard!

These men represent the 7th Neapolitan Infantry, attached to and later partially subsumed into the Young Guard in 1813 after the disaster of the 1812 Russian campaign. The history of the 7th Neapolitan is complex and confusing, with a lot of contradictory sources on exactly what happened to the unit and the men within it during its service with the Neapolitan and French armies. Initially one of the Pioneers Noires units, a racially segregated amalgamation of Caribbean and African soldiers, in 1806 some of the Pioneers passed into service with the Kingdom of Naples, becoming the 7th Infantry “Reale Africano”. In 1812 they marched – in bright white uniforms – alongside the Russian campaign, but were spared the worst of the retreat with a posting in Gdansk. There were still enough of the Black African soldiers in the regiment in 1813 that they were remarked on in many sources of the time.

After that, it gets confusing. According to some sources Grenadiers and Voltiguers – the best soldiers forming the flank companies – were detached as an elite company to the Young Guard. Sources differ as to whether this was a formal amalgamation into the regiments of the Young Guard or an ad-hoc posting to temporarily bolster numbers. The rest of the regiment fought throughout the 1813 German campaign, distinguishing itself at Leipzig, eventually going back to Naples when the Napoleonic Empire crumbled.

What happened to those guys who were sent to the Young Guard? Some of them would have been decade-long veterans of the coalition wars. They were the Elite of a renowned regiment in Napoleon’s closest ally state, Grenadiers and Voltiguers, men that the Emperor sorely needed, and needed within his personal army. It’s not unrealistic, or ahistorical, or even unlikely, that the officers and men of the Elite company of the 7th Neapolitan were given a blue greatcoat, earned their epaulettes, and fought under a Tirailleur fanion.

Digging into race and Napoleonic history is far and away beyond my level of understanding of the period, but I’ll get there. At the moment I just wonder what kind of experiences these men had, the lives they led before and after the wars. Did they buy into the whole Napoleon myth? Did any take up arms again and march on Waterloo? Did any of them go back to Africa and the Caribbean? Did they want to?

Pretty Vacance

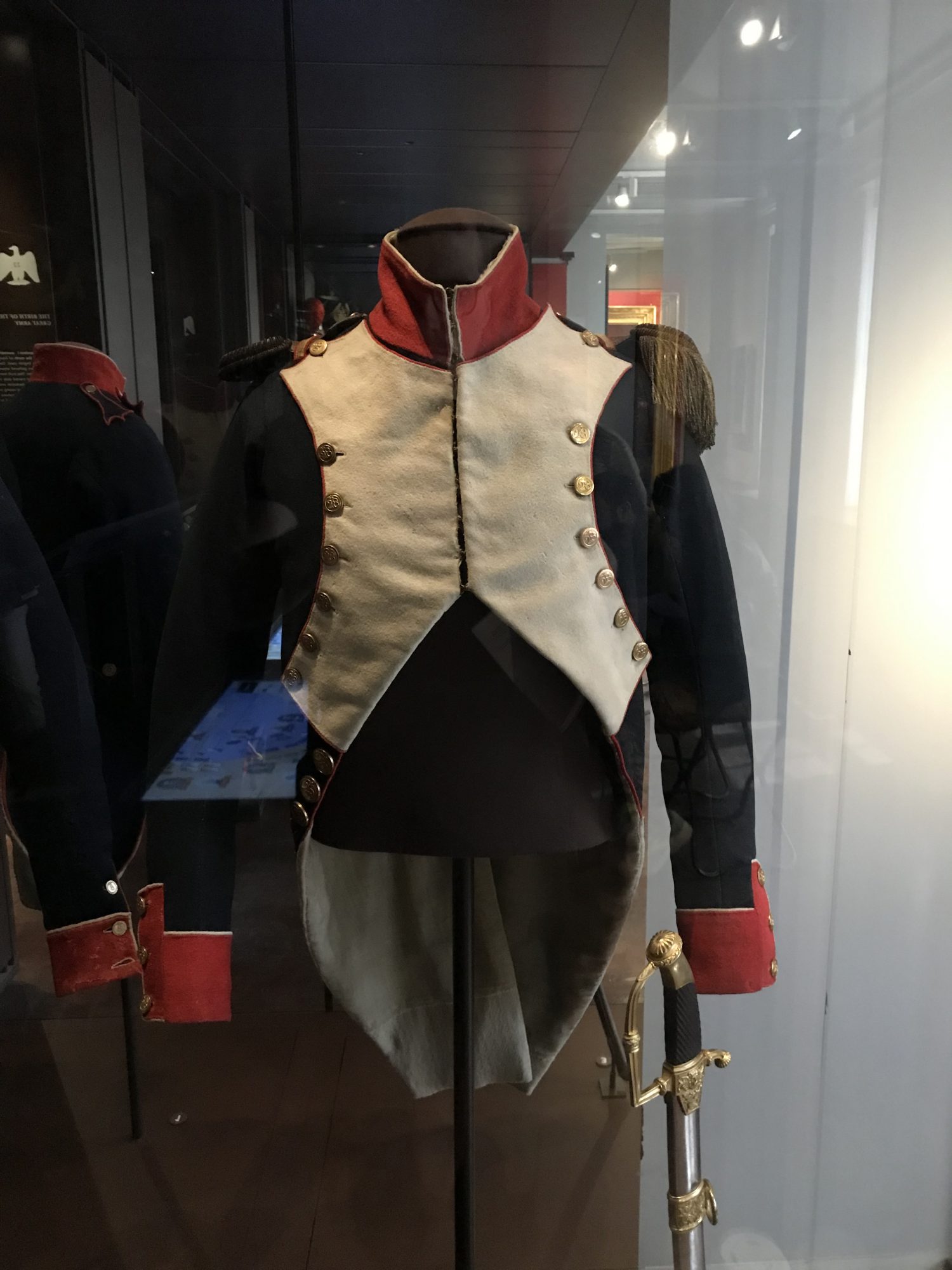

I haven’t done that much hobbying for various reasons this month, but the biggest reason is I spent a bit of it doing serious research while on holiday. I’ll spare you all a massive gallery of slightly blurry holiday snaps, but I will strongly recommend that if you live in a country where a trip to Paris is doable on a tight budget, you really should go to the Musee de l’Armee. Not just a fantastic museum for the militaria-minded, but a great and to be honest unabashedly pro-Napoleon gallery of 18th century warfare. I thought I’d go and learn a lot (which I did), but I mainly spent my time looking at Uniforms. Oh man, the Uniforms.

-

1812 Issue Shakos -

Line Officer Uniform -

Grenadier Guard Uniform -

Tobacconist’s sign, mid 19th century. Musee Carnavalet

A fantastic reference collection for anyone painting frenchmen, but also a great comfort. Most of the line uniforms – and a lot of the guard – are miscoloured, faded, badly stitched, irregular and tatty. Not just because of age, strange curatorial choices in the 20th century and being moved around to avoid the various wars, fires and other calamities that Paris has faced, but because they were made that way. There’s old buttons on new uniforms, there’s non-regulation plates and shakos, even within regulation issues there’s huge variation based on where things were made. Uniforms are made poorly, out of material that doesn’t hold dye well, and these were the best ones on display! My takeaway from a full day staring at just the Napoleon galleries is this:

It is historically accurate to mix uniform types, convert, bash about, wear, paint the facings wrong, use different colours, miss off buttons, add (or remove) epaulettes and generally do pretty much whatever you want.

After all, Napoleon and his men did, so why shouldn’t we?

The one, unfortunate, exception to this is the Hussars. There’s no way they shouldn’t get the full and undying respect of every modeller and painter, because holy shit their uniforms look even better in real life.

Reading, always Reading

The main reading this month has been Andrew Roberts’ Napoleon the Great, aptly named because it’s Bonapartist as all hell, but enjoyable and a good read so despite the fact it’s a monumental door-stopper of a book I’ve been hurtling through it at a rate of knots. Have to disagree with Roberts assessment of a couple of things, most of all that Napoleon was really quite an arsehole, Toussaint was awesome and Josephine not the frivolous idiot that he seems to think.

Onto Napoleonic Badass of the Week (or month?), and this one is close to home. In 1797, British sailors at the Nore and Spithead anchorages mutinied, downing tools and refusing to work (and fight) until their grievances were addressed. At Spithead they fought for better pay, food, shore leave and injury compensation, some of which they achieved. At Nore, they went more radical, demanding eventually the dissolution of parliament and immediate peace with France, or they’d up anchor and go join the French fleet. Over May and June 1797, sailors and whole ships slipped away from the mutiny, leaving its ringleaders metaphorically and literally high and dry. Several were hanged – and our badass of the issue goes to Richard Parker, elected “Presidents of the Delegates of the Fleet” for the sheer chutzpah to threaten senior figures of the Royal Navy that he’d lead ships to sail for French shores. Strung up on the yardarm to show the proles what wanting better treatment would get them, his death was a final act of reprisal for embarrassing the Admiralty. His wife managed to seize his body and smuggle it into the near-mutinous city of London, making his grave a minor pilgrimage point for rebels and radicals for decades afterwards. Good on him, I say.

Next time: I haven’t decided yet

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.