There is still technically time for this to change, but at this point in the year — lurching into October, with much of the release schedule for the rest of 2021 dead in the water — I think Psychonauts 2 is my game of the year. Possibly for two years.

The first Psychonauts turned 16 years old this April, if you want a sense of how long Double Fine Productions has let this one linger; their most recent big production was Broken Age in 2014, an extremely regrettable dalliance with Early Access in Spacebase DF-9 that same year, and a bunch of remasters and contract mobile work between then and now. Perhaps the last really big title that you heard of from the studio was Brütal Legend back in 2009. They’ve been maintaining their revenue streams, yes, but they’ve been lurking and working on a labor of love for quite some time: the sequel to the platforming collect-a-thon that put them on the map.

The logline for Psychonauts 2 is essentially the same as the one for the original game: what if a Nickelodeon mid-Aughts cartoon with Emmy-winning writing was the narrative backdrop for one of the tightest platformers of its generation? And it’s been so long since the first game, of course, that they’re no longer in conflict with each other for that “of its generation” title. In the first game you play the ten-year-old child Razputin Aquato, who has escaped his circus acrobat family to go to summer camp to become a Psychonaut, which is some sort of narrative-gentle cross between a therapist and a cop. In the second game you are still young Raz, literally a week or two later (though fifteen years have passed in real life and those of you who played the first game on release are now going gray), as his success at ferreting out the evils at the heart of the Psychonauts’ young paramilitary recruitment center have gotten him a new gig exploring the past failures orbiting the sickness at the heart of the Psychonauts themselves, and in the process unveiling a dangerous mole in the organization’s midst.

In both games, this plot is a skeleton to hang some seven to nine levels off of, and these levels are all the broken brains of the adults in Raz Aquato’s life — in the first game, his camp counselors; in the second game, the well-aged, self-deluded and traumatized founding members of the Psychonauts, who had to put down one of their own and were near-irretrievably shattered by the experience. This is all handled, again, with the general aesthetic touch of a Nickelodeon or (now) Netflix animated show; the sort that is definitely suitable for and aimed at early teens but finds a strong fandom with adults due to being competently put together genre work with a throughline. It’s worth noting that the level of quality in that storytelling is far closer to a Steven Universe than it is to…well, whatever Netflix is running out there.

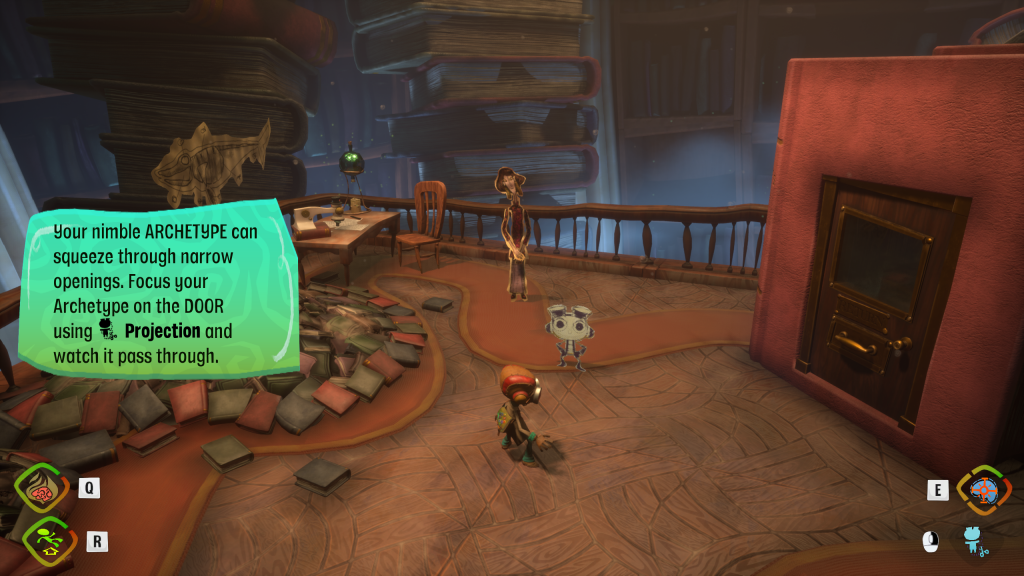

In both games as well, there’s a collect-a-thon aspect to these levels. You need to collect Figments, which same as the first thing are little cartoon doodles of thematically important topics to the brain which are scattered comprehensively about the level; you’ll collect some sixty to eighty percent of them simply by moving in the directions the game wants you to go, and they’re often used as guideposts in this fashion. The remaining Figments, of course, will give you fits if you’re a completionist. There’s Emotional Baggage, which is crying luggage that you need to find matching baggage claim tags for. New to the second game are Nuggets of Wisdom, which are just straight level-ups (there are extremely light RPG elements here). There are Half-a-Minds, little, well, half-brains that give you an extra health bar chunk (portrayed as actual brains) for every two you collect. It might be difficult to remember, but this is actually streamlined from the first title — Mental Cobwebs are gone; Psychic Arrowheads are gone; there’s an entire ammunition system for the first title that has been ripped out and the game is better for it.

In many ways, the second title isn’t really a sequel to the first, but a direct continuation thereof, quietly refining some systems but in many ways being the best game not just of 2021 but 2006; all the systems that are present here would have or could have been present then too, and the ways in which they’re used make this feel like something that could have been penciled into the schedule for 2009 or 2010…but they decided to really take their time with it, let it mature and do it right. And they have done it right; the master craftsmanship is present across the entirety of the game’s visual and mechanical design.

The real treat is in the brain-worlds themselves: the imagination with which they’re realized both in setting and art design, combined with the mechanical and thematic novelty in how they interplay. There is a brain that is actually a cooking game show, in which you have to face the person’s anxiety about inadequacy in the face of the expectations of his friends. There is a brain that is based off of groovy Woodstock, where you have to reunite a character with all five of his senses after he’s blocked them out due to extrasensory overload. There is a brain that is actually four smaller brains, as Ford Cruller from the first game returns and this time Raz has to take a deep breath and actually help put the old man back together. Many brains introduce new psychic powers for Raz to use, but not all do; one of the great demonstrations of skill in Psychonaut 2’s design is that rather than leaning on “we’re giving you the new ability Slow Time, and this is the level where mainly what you’ll be doing is slowing time” for each brain, a number of them — the aforementioned Ford Cruller shards especially — are about remixing your understanding of previous powers and using them in new ways; there is, for instance, a bowling alley level where you use the rolling ball traversal part of your Levitation power to solve the level rather than the hover-balloon bit; you already had a level focused on the hover-balloon bit back in the first game!

Throughout all these worlds, you meet the brain-phantoms of the other old men and women from the original Psychonauts — the avatars of who the person whose brain you’re in perceives them to be, fairly or unfairly. In the brain of the cooking show guy, he saw his old friends as the judges, but also as goats: pushy, demanding, incredibly critical of his food…but also totally disinterested in savoring or appreciating it, stuffing it disgustingly down their throats until they burst. The game respects the player enough not to have someone actually say out loud that this is how he feels his colleagues have treated him; it’s obvious enough. Meanwhile, the Woodstock lovefest guy sees the other founding members of the Psychonauts as members of his extremely-close knit band, one standing in for each of his senses — and each one similarly taken away from him when he lost his body (you can remove brains from bodies pretty easily in the cartoon sci-fi world of Psychonauts; getting into the specifics here would constitute spoilers). And Cruller, of course, is stuck firmly in the past — back in the place and time that literally broke his brain.

The plot is well-constructed and well-executed; the main thrust of the story is that there’s a mole within the Psychonauts and it’s your job to ferret out who it is and help nebulously save the day (what that entails changes a couple times over the game), and one appreciates that Double Fine pulls off the high-level technique of making the mole twist an artful two-parter: by the time you reach the reveal, you will have figured out who the mole is if you’ve been paying even the slightest amount of attention…but this twist is accompanied by a second, more important one that, while also supported by previous events, is very difficult to see coming from inside the story (rather than, say, stepping back and looking at the pieces on the narrative board and playing Chekhov’s Gun with them, which will eventually get you there). It’s nice! It’s very well done. Again, we’re talking the stakes and aspirations of like, a Nickelodeon show here, but it knows the assignment and it completes it well, managing to stay both affecting and all ages.

If there’s substantive criticism to be had, it’s in how, precisely, the power mechanics are handled: you get eight powers, but can only equip four at a time, each of which maps to a trigger or bumper. If you want to change your loadout, you have to go into the powers menu (which is just a D-Pad touch) and reassign a button mapping. It would have been just as easy, however, to have that D-Pad touch simply flip two sets of preset mappings, giving you access to all eight powers without having to hit a menu screen, and making you specifically more fluid and dangerous in combat. This would have been obvious to Double Fine, and it’s just as obvious that they set up the mapping the way they did for very considered reasons. One suspects they’re for simplicity’s sake: they limit the amount of actions you have available to you at every time because they’re confident they’ve designed levels and encounters that don’t require access to more than four powers at once, and the challenge to you as a player is to analyze the level and determine which of the powers are most applicable. After all, if you have access to all eight powers, it is reasonable to assume you will be expected to use all eight powers. And that maybe sounds like something to keep in reserve for a slightly-older and wiser Raz Aquato in Psychonauts 3, should that come down the pipe sometime in 2036. Of course, if this is the final ride of the Psychonauts, that’s fine too: all the hanging plots have been tied off, the themes wrapped up and delivered upon, and fifteen years later, everyone can go home happy.

Final Verdict

Game of the year for me at the moment; available for $60 on Steam and other places PC games are sold. Graphics are very good and of a sufficient art style that high settings won’t cause even older computers to chug — the only place in the game I had even the whisper of a performance problem was in the large sidequesting area you get access to in the campgrounds. Games like these don’t come around very often and in a drought of big releases like the one we’re currently suffering through, you should unparch your throat whenever you can.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.