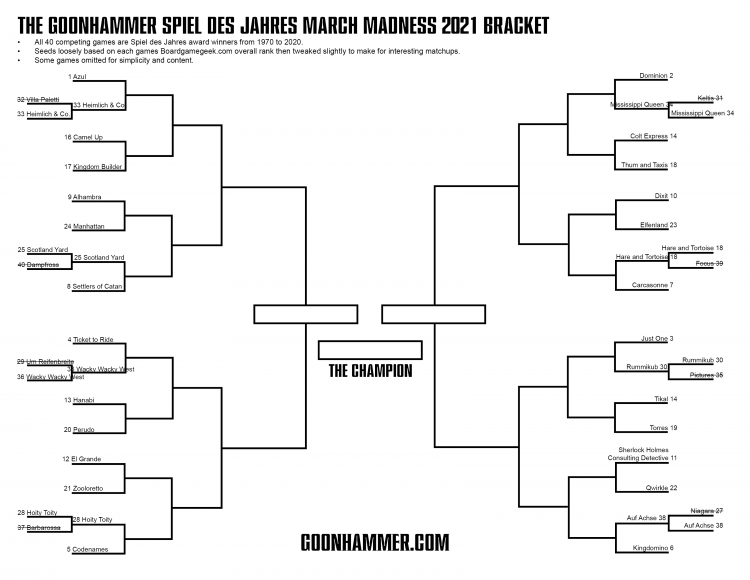

Wondering what this is all about? The Turn Order writing crew is talking about every game to ever win the Spiel de Jahres award—think of it as the Oscars of Board Gaming. We introduced the bracket and spent some time with the “Play-In” games in each bracket. You can catch up on all our coverage here.

With the Play-In games done, the main bracket is set. This is what’s known as the Round of 32 in NCAA Tournament parlance; at this point Vegas has slowed down a little bit, due both to the lower number of games and the 2-day hangover starting to set in. The basketball tournament opens with the Round of 64 on Thursday/Friday and moves right into the Round of 32 on Saturday/Sunday before the “student athletes” return to campus to study classes film.

We’re going to go region by region talking about every game, while also picking a winner for each matchup. For those unfamiliar with the terms, winners of the Round of 32 head into the “Sweet 16”. From there it’s on to the “Elite 8” and ultimately the “Final 4”.

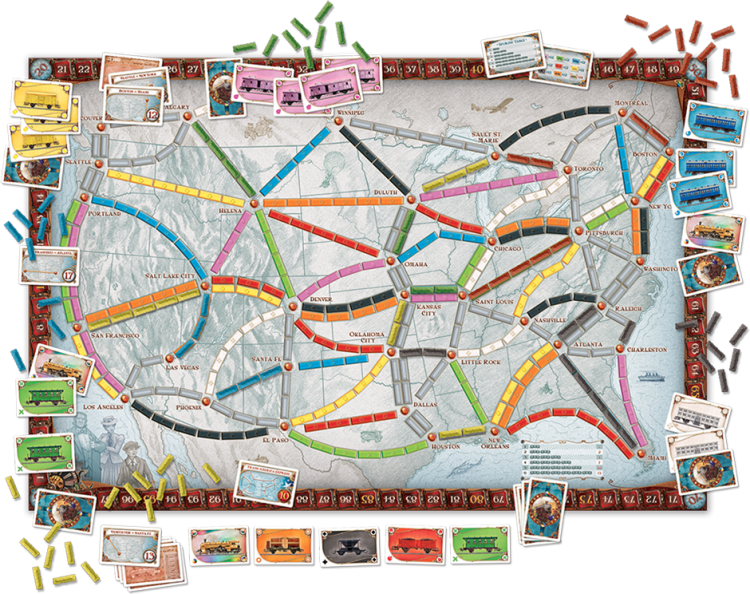

Ticket to Ride

Trains – who doesn’t love trains? And who doesn’t love a board game where you crush your friends’ spirits by criss-crossing American with tiny colored train cars? Winner of the 2004 Spiel de Jahres prize, Ticket to Ride is a game about railroad expansion.

The mechanics are pretty simple—collect sets of cards of the same color to complete routes between cities. Some routes are short—just two slots—but others are much longer and consequently harder to finish. But connecting any two adjacent cities is never enough to actually score points. No, for the really big payoff, you need to go farther—say from Boston to New Orleans or New York to San Francisco. Each player will have a hand of routes (drawn at random, though it’s generally a “draw three keep at least one” kind of deal so you have some control over your fate), and these are kept secret. And secrecy is important, because you are competing with your friends over limited rail line rights-of-way between cities. Between many connected cities (say Kansas City to Denver) there are two possible routes, but if you’re trying to connect from Denver to Phoenix, there’s only one.

And once the connections are gone, you’re stuck either having to go the long way around, connecting through other cities to get to your destination, or you’re stuck eating the loss incurred by unfinished routes at the end of the game. This gives lots of opportunities to screw up your friends’ carefully laid plans. Do I absolutely need to drop two trains to connect New Orleans to Houston? Of course not, but if I suspect that you do I’m going to get there first and make you divert through Dallas and Little Rock, laying 6 trains along the way. Sucker.

Ticket to Ride is one of those great games that causes you to balance your approach: you get some points for laying track and connecting cities, but the big points come from completed routes, and the longer the route the more points it gives. But again, unfinished routes count against you at the end of the game, encouraging players to balance the risk vs reward of going full-on transcontinental. This game has been a perpetual favorite in our house because it’s very easy to learn and very kid-friendly. And really, who doesn’t love trains?

Wacky Wacky West

Wacky Wacky West won its Play-In game on the strength of its hidden information and pseudo-cooperative bluffing. We love it for that! But Ticket To Ride is one of the best selling board games of all time for a reason and WWW is going to struggle in this matchup mightily.

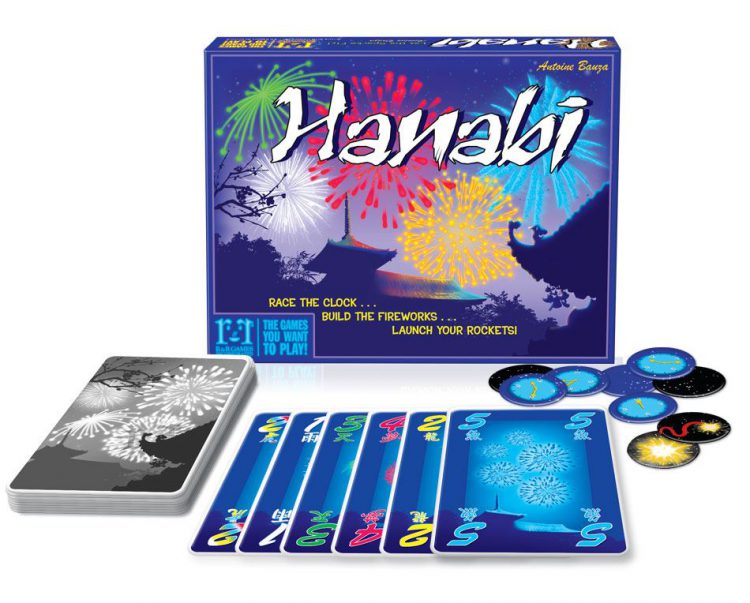

Hanabi

If you had to reach into a crate of fireworks without looking and pull something out you hoped would look fantastic up next in an explosive show, how do you think you’d do? Now, imagine that as a card game – sort of a strange concept, I get it. But Antoine Bauza ran with it and made the co-operative deduction game Hanabi.

The Hanabi deck consists of five colors of cards, each numbered 1 through 5. To successfully pull off a fireworks show with your fellow players, you must play cards into five piles by color, in ascending order. Sounds easy, right? But in Hanabi, all players must hold their hand of cards facing out, meaning you don’t know what your cards are from the get-go. Players work together to provide (limited) clues to each other and using that information, and what they can see in other players’ hands, play cards out to the “fireworks show” and hope for the best.

On your turn, you’ll take one of two actions. Play one of your cards to the table and hope that it’s the next in succession for that color, not messing up the show. Or, you give one clue, to one person, indicating either the color or the number on certain cards – that is, pointing at certain cards and saying “these cards are blue” or “these cards are threes.” As the game progresses, slowly the web of information at your disposal will coalesce and hopefully you won’t have to play cards without knowing at least a little context of what they could be.

Hanabi was a game that took my gaming groups by storm, and I certainly remember back to back games as we all worked at manipulating clues in the best ways we could to become successful fireworks masters. While its fellow SdJ nominees Qwixx & Augustus are certainly great games, they don’t come close to the unique flavour of Hanabi. There’s a lot of games that would be hard-pressed to show up the unique simplicity of Hanabi, to be honest – and I feel like that alone would make it a game that should shoot through these brackets.

Special thanks to Nicole Hoye of the Daily Worker Placement for contributing the Hanabi write-up.

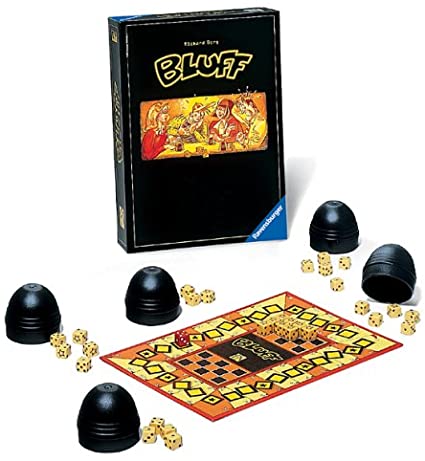

Bluff aka Perudo

Ok this is a weird one. Perudo, also known as Liar’s Dice, can trace its origins back hundreds of years and is a gambling game played on streets around the world. Bluff aka Call My Bluff aka Perudo (ish?) is an extraordinarily similar game designed by Richard Borg that he based on Liar’s Poker, a bar-betting game that is a riff on Liar’s Dice. Still with me? I wouldn’t blame you if you aren’t. Whatever you want to call this game, it’s a dirt simple dice game that sits squarely in the intersection of statistics and bold face lying which is itself also just the entire field of statistics.

In Bluff players have a handful of dice and a cup. Shake the cup and slam it down and take a peek at what you’ve got, keeping it a secret from the rest of the table. At this point the betting begins. Knowing only what you’ve rolled you have to make a bet comprised of 2 parts: a number of dice and a pip-value. For example, betting “four twos” means you think there are at least four dice showing 2 pips among all the players at the table. The next player can either challenge, which forces a table reveal, or raise. Raising involves raising one of the two parts of the bet, or both. In our example you could say “Four threes” or you could save “five twos”.

I’ve played a card based version of this, and a version called Skull that uses decorative coasters. Whatever version, they all feel the same and are a good bit of simple bluffing fun. I doubt this wins the Spiel these days, but at the time it was revolutionary and launched Borg into a career that would eventually bring us games like Memoir ’44.

El Grande

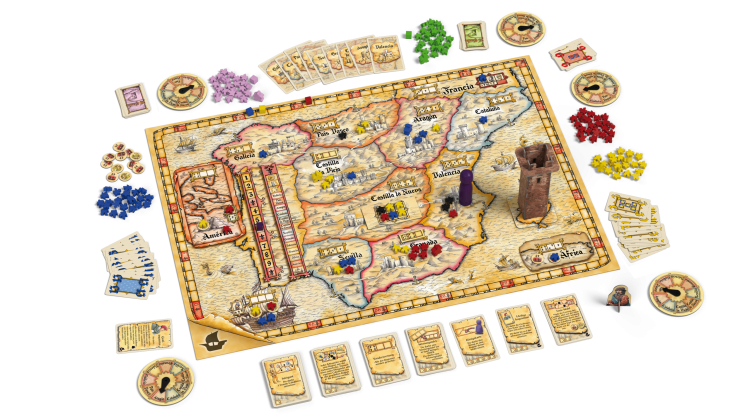

El Grande. That’s Spanish for “the Grande.” And it’s the granddaddy of area control games, a tense affair that will have you and your friends on the edge of your seats as you scheme to position yourself as the most powerful of the King’s vassals by deploying your caballeros to control the various regions in Spain.

Play is deceptively simple: first, you play one of your 13 Power Cards, which will both determine your turn order and allow you to recruit a number of caballeros (the cubes you’ll use to control regions) that are available to be dispatched later in the round. Then, in turn order, each player will choose an Action Card from the table, which will let them deploy their caballeros to take control of regions on the board for scoring and give them a unique action they can take to shake things up on the board. Then, at the end of every third round, you’ll score points based on who’s got the most cubes in each region.

There are a few hiccups, though. First, the more caballeros you recruit with your power card, the later in the turn order you’ll go. You can guarantee that you’ll go first, but doing so won’t let you take any cubes from the supply, so you’d better have stocked up in earlier turns. In addition, once you’ve used one of your 13 cards, it’s out for the game. The Action Cards are similar: the more caballeros you deploy, the weaker the power you get, with 4- and 5-cube moves coming with tamer powers, while the 1-cube cards actually let you move your opponents’ pieces around.

Complicating all of this is the King, who moves through his Kingdom on inspection, preventing players from adding or removing cubes from the region he’s in. But the real chaos comes from the Castillo, a cardboard tower that stands imposingly off the coast of Spain, offering opportunity to those who can take advantage of it, but only ruin to those who can’t. Whenever you use your action card to place your cubes on the board, you can instead place any number of them in the Castillo. It counts as a region like any other, scoring out each round based on the number of cubes in it. There are two important caveats regarding the Castillo, however. First, it’s a cardboard tower that you can’t see into, making it harder to keep track of who’s winning as you close on the end of the third round and have been planning your own strategy while trying to keep count of who’s in the lead in the Castillo. More importantly, though, once you score the Castillo, each player secretly chooses a region for all the cubes they put in the Castillo to go.

Unlike actions, you can choose any region (other than the one the King is in, of course), potentially shaking things up in a place the rest of the table didn’t realize was in play. And because you score the Castillo before any other region, choosing the right region could swing the score and steal victory away right at the end of the game. It is entirely possible – and even likely – that one of the three scoring rounds of any given game of El Grande will end with all of the players groaning in frustration as they realize they either made a mistake when choosing which region to send their cubes to, or simply lost track of how many each player had in there, causing them to wind up scoring fewer points than they’d hoped for.

In retrospect, El Grande offers everything you need to be an instant classic: simple mechanics, low randomness, and plenty of opportunities for a clever player to throw a spanner in their opponents’ works at just the right moment. It may be somewhat dated and understated compared to some of the flashier area control games on the market, but even now that it’s going on 26 years since its 1995 release, it’s definitely worth a play.

Zooloretto

Zooloretto won the 2007 Spiel des Jahres but it was essentially a “two-fer” award for designer Michael Schacht. Four years prior Mr. Schacht released Coloretto, an outstanding card game – and Zooloretto’s muse. The lineage is clear when you isolate the Coloretto Gene™ – a dead simple core mechanic that both games share.

Each game gives players the tantalizing choice to either 1) draw and add a card or tile to a row on the table or 2) to take all cards/tiles in a row and opt-out of future draw/place choices for the rest of the round. In both games the rows you can play to each round correspond to player count and each row’s capped at three, which provides a delicious “should I or shouldn’t I” press-your-luck frisson. And in both games ruthless efficiency is prioritized: you only gain points for your top three scoring sets, and are penalized for sets you gather beyond the Top 3.

Zooloretto expands Coloretto’s card-only métier by swapping in animal tiles you collect to complete the best zoo enclosures. Complexity is increased as well: players must fill their zoo enclosure “bingo cards” completely for maximum points. There’s also money and a budget menu of special actions (renovations, expansions) you can take by spending it. Finally, animals are male or female and thus beget offspring (free animal tiles) in your enclosures if you play matchmaker. (Apparently animal husbandry was all the rage in 2007; Agricola was released that same year. Though in Zooloretto you aren’t frantically sweating out every moment of the game trying not to starve, thank goodness.)

High on the list of “fun things people like to do in games” is to collect sets. Zooloretto’s “add-or-take” central mechanic generates an endlessly renewable resource of groans, regret, and schadenfreude at the table. Add to that the fun factor of its zoo theme and Zooloretto is a blast. Zooloretto is an example of a game mechanic redeployed to create a brand new game experience from the same strand of DNA. Whereas Keltis takes its Lost Cities card mechanic and just adds a board, resulting in a samesy, fungible, and even lesser game, Zooloretto soars by adding weight and heft to the same core as Coloretto and fuels it with the pleasing endorphin rush of getting to make something with warm and fuzzy mammals.

Hoity Toity

Hoity Toity burgled its way in from the Play-In game, carried by its theme of Cool Art Crimes. Like many of our Play-In game winners, it sticks out among the other contenders but is certainly enjoying its time under the lights.

Codenames

Codenames is one of those party games that game in hard and fast, taking the game world by storm. It was very quickly (and profitably) spun off into various versions like Pictures and licenses like Disney or Marvel. It’s a winner because the structure is very simple yet requires you to piece together the mental leaps you think your friends would make balanced against the tension that comes from making it very easy to help your opponents.

Play is fairly simple. Lay out a 5×5 grid of cards that have single words (or pictures, or stills from Little Mermaid, or whatever) and split into teams. Each team has a single Spymaster who joins their opposing Spymaster at one end of the table. These two grab a Key Card that represents which cards belong to the Red team and which belong to the Blue. It also shows which word in the grid is the Assassin.

The job of the Spymaster is to get their team to guess their words as fast as possible, by giving clues made up of a single word and a number. “Animal 3” would mean, in theory, that the Spymaster thinks there are 3 cards on their team related to Animal. This clue is far more basic than what you end up having to give, however. It’s rare that you have something as clean as 3 animals in your color, 0 in your opponent’s, and also have it be unrelated to the Assassin clue. What makes Codenames tick is that if your team guesses a card belonging to the other team, the other team scores it. If they guess the Assassin, you lose.

The joy here comes from figuring out how to get your team to guess the words “Mug” and “Stadium” while the word “Beer” belongs to your opponent. If you say “Sheep 2” they’ll probably get Wool, but will they key in on Kiwi or is that too esoteric of a connection. Now you risk confusing them as they struggle to guess that word on future turns. Play evolves as they get some right and some wrong, words are covered up or guessed by the other team, and the Spymaster is left wondering how to get folks back on track.

Codenames is a fantastic party game that is easy to teach and play. It does, however, have a couple of flaws. Notably it’s fairly low energy. Yes, big guesses will elicit whoops of joy, however most of the game is spent in pensive silence. Additionally, it’s very easy for the Spymaster to key in on a single person and give clues that will only be picked up by a partner or best friend and leave others behind. Despite those quirks, it’s still worth playing and the myriad licenses ensures it’s easy to hook anyone.

Bracket Wrap-Up

In the top half of the bracket, Ticket to Ride doesn’t even make a stop in the Wacky Wacky West, cruising straight through to the Sweet 16 where it also handedly dispatches Hanabi. Hanabi and Perudo is an interesting matchup. Perudo is bluffing and betting distilled, and Hanabi is in a way the inverse of that. You know everything except your own information and rather than trying to hide info you’re trying to efficiently share it. That gives it the edge over Perudo, even if it can eventually turn stale if you play it enough times.

Down in the lower half things get much more interesting. While El Grande and Codenames both easily advance into the Sweet 16, this match-up proves to be difficult to resolve. El Grande has the weight of history and influence, while Codenames is more accessible and you can play with anyone. You can also play with any thing; during the height of Codenames mania it wasn’t uncommon to see people laying out 5×5 grids of everything from board game boxes to hot wheels cars and successfully playing Codenames. Ultimately, however, El Grande is going to take this one. It’s good, real good, and unlike many of the older games in this competition still holds up great.

Bracket Winner – El Grande

Damn this was close. Real close. Comparing these great games has been an exercise in splitting hairs. In our previous Road to the Final Four articles we gave the nod to Azul and Carcassonne over their competitors based primarily on which one we’d rather play right now, today. In this match-up both games are still easy to recommend. Which you pick is down more to the mood and audience than anything else.

So why El Grande? Well when both games are still easy recommendations we’re eager to play we’re going to go with the one with the more impressive legacy. El Grande put area control on the map, is still a top choice in the genre, and has inspired games that came after. Ticket to Ride is not quite as mechanically inspirational, despite being one of the most successful gateway games ever. What finally tips El Grande over is that you can play El Grande forever. Base Ticket to Ride will eventually run a little stale, particularly with the same group. Expansion maps exist in spades and again, they’re almost all great, but El Grande can stand on its own for a bit longer.