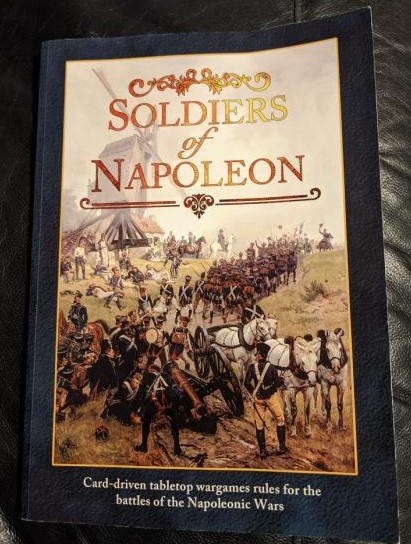

Soldiers of Napoleon is a 2022 miniatures wargame by designer Warwick Kinrade and Artorus Games designed to emulate battles of the Napoleonic Wars. Unlike many other games in this genre it is a genuine attempt to portray, in a number of innovative ways, the broad sweep of an entire battle while keeping the experience playable with miniatures on a table that might plausibly fit inside your house. The result is a rough gem, a host of great ideas and innovative solutions that could have used a little more polish but is still absolutely worth your time.

The book covers a card-driven rule set for mass Napoleonic battles and army lists covering the major powers of the later coalition wars of 1813-15, including a 55 card deck of actions. It’s illustrated throughout with models from the Authors own collection with well written granular summaries of the battles and campaigns it covers.

Before we get started, we’d like to thank Warwick and Artorus Games for sending us a copy of the book to review.

Some Corner of a Foreign Field

There are lots of very interesting things to talk about when it comes to Soldiers of Napoleon, but let’s get right into one of the parts that’s likely to stir up the most discord in those who read it: the main way that it handles large battles. While you can happily portray smaller Divisional games and do so comfortably on the tabletop, the game is clearly intended to really shine at larger scales. With a small division your troops are all that exist in the battle, the table is the entire field and your fight with your opponent is all that matters. Not so with larger games.

With larger divisional games your general is still the overall commander, but there will be reserves arriving from elsewhere during the game. At Corps and Army scale games, the real meaty battles that are an evening or day of play to get through, you still only have a division on the table but the rest of the battle is still going on elsewhere.

This manifests itself in a few different ways. Your commander is probably not the person actually in charge of the overall direction of battle, and so there are added considerations around the chain of command. The general in charge might well show up to help out at some point, as he attempts to shore up the areas of the overall battlefield that need his personal attention. You may also have access to a large number of reserves, as soldiers from other parts of the battle show up to help out.

While a nice place setting aspect, and a way of getting more troops on the board across the course of the game without crowding it at the beginning, the really controversial choice is that how the battle goes elsewhere affects your troops in the field. The battle that, notably, no one is playing and you have no control over. This is done very simply through a “How Goes the Day?” roll during the turn wrap-up phase. This determines the initiative going into the next turn, and can also end up rewarding additional victory points to one side or the other. Though the number gained isn’t huge by any stretch of the imagination, I baulked initially that some element of “whether I win or not” being pegged to a single roll off with my opponent.

Now, it’s not quite as random as this makes it seem – the roll off uses your army’s “tactical advantage” as a modifier. So what is a tactical advantage? Well, it’s made up of the operational advantage of your army (set by the army you choose and modified over a campaign), how many scout units you have in your force, and what tactical order has been issued (what mission your commander has been given by high command, each of which give some advantages and disadvantages). This means you get a lot of control over what your tactical advantage modifier is, but mostly at army creation. It also means that some armies are just… better at this. Is this accurate to the historical record? Yes absolutely. Does it feel a little frustrating that you’re potentially hampered by playing a specific force in such an arcane way that can, in theory at least, end up winning or losing you the game on a random roll? Also yes. Does it let you play the division that makes the battle winning strategic move rather than just grinding your troops together? Emphatically yes.

It’s an interesting choice, and I may not agree with the entire execution of it, but it’s hard to argue that it doesn’t strongly evoke the kind of battles that took place in the period, and enhance the sense of fighting a large, somewhat unwieldy and chaotic, battle. And this is really Soldiers of Napoleon in essence: I do not personally love every single decision made, but it’s hard to overstate just how much these interlocking rules work to create a specific feel and theme. If that was its only virtue it would be a considerable one, and one I would applaud. But it also has the advantage that many of the ways it does this, many of its innovations, are fantastic.

Men of Action

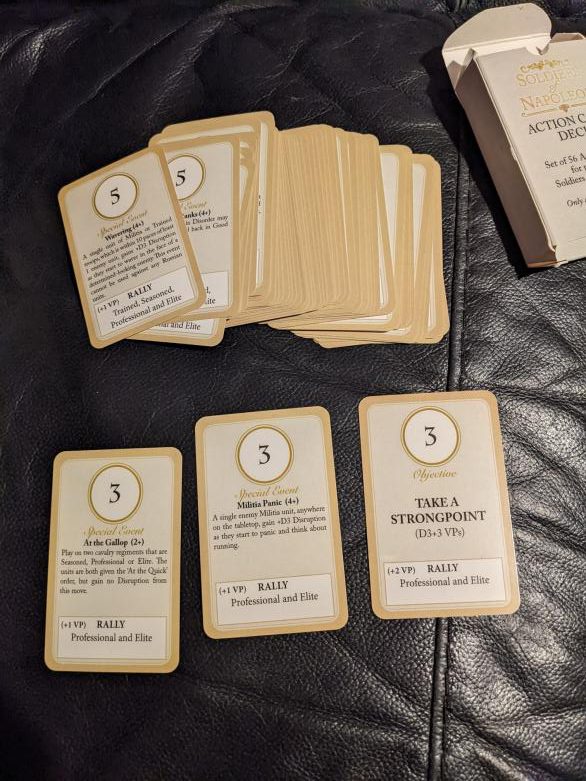

At the heart of Soldiers of Napoleon lies the Action Card system. This deck of cards, which comes with the rulebook and is an absolutely essential component of the game, is absolutely fascinating. The deck is shuffled and players will draw from it each turn, taking 2 cards and then 1 for each command stand on the table at the beginning of the turn. Thus if your commanders are captured or killed then you’ll find your ability to control the flow of the game hampered, a simple but effective way to both incentivise you to keep them safe and also to portray the collapsing chain of command as a battle goes against you.

The cards themselves can be used in three different ways:

- To play for orders, granting a brigade commander a number of orders to hand out to units under his command

- For a special event that allows your troops to act in a way not normally allowed by the rules, or grant them special bonuses

- To rally troops. This, in particular, is a brilliant innovation in this ruleset and we’ll come back to rallying in more detail in a bit.

This flexibility is a wonderful aspect of the card system. Though you only have a handful of cards at any one time, you feel like you have a huge amount of choice on how to play them. It also balances cards nicely – cards that are excellent in one regard will be less powerful in the others. I’ve seen systems similar to this in part before, but never so elegantly executed in such a coherent way. This action card system is the key to the whole game, and what a delightful and compelling key it is.

Card driven activations are a familiar groan in the historicals community, usually leading the more difficult kind of grognards (as opposed to the awesome kind) to complain about “playing the game not the period”. But this is card activation done exactly right, forcing meaningful choices, driving a narrative and simulating the friction of the battlefield. You have to play the game, literally, with the hand you’re dealt, but with most cards having three different uses and occasionally including minor or major objectives, there’s always something you can do – the question of what comes down to you, and you will need to assess, prioritise and make bold decisions with every card.

To Be Able to Decide

That choice is one of the core themes running through the system as a whole. Every element of the game prioritises player choice, and you’re only very rarely going to be forced into a single play. Soldiers of Napoleon ties those player choices into the Napoleonic theme so that you’re really there, working out your options and thinking in as close to division level command as you’re going to get with miniatures in the 21st century. It feels right, as well as working right.

The core rules of movement, formation and orders are flexible, largely clear and provide more meaningful differentiation between unit types than other mass battle Napoleonic rulesets. Simple special rules, unique orders and easy to understand unit profiles make your battalions and squadrons behave as they should. Ordering the various infantry and cavalry types you’ve deployed into action gives you a feeling of battlefield mastery, coming into a crisis with exactly the right bit of the swiss army knife ready to use.

Lots of mass-battle Napoleonic systems have difficulty with different units (particularly the bewildering array of cavalry types) and making them meaningfully different on the field, not just in ability, but how they act and what they are. Soldiers of Napoleon gets there through granting access to variant orders and interactions with the order cards to different levels and types of unit. Light cavalry can scare off skirmishers, heavy cavalry can scare the shit out of line units just by looking intimidating. It’s a simple, clear and easily used system rooted in the battlefield realities of the period that has a lot of scope for additional variant units in the future. The design space here is huge, and it’ll be interesting to see what Warwick does with it in other theatres of the Napoleonic wars.

We have lost the day!

An entire phase of your standard wargame gets a really innovative boost in Soldiers of Napoleon with Disruption mechanics, really transforming an otherwise often brushed off or minimally explored part of the mass battle game – rallying.

Disruption represents casualties, loss of command and control, morale and fighting efficiency, all the ways in which Napoleonic era units tended to waver, break or otherwise diminish. Disruption can be inflicted by your enemy – being shot at, or caught in hand to hand combat inflicts loads of disruption – but it can also be put on your units through command decisions. This adds lots of clever, very Napoleonic, twists to the battlefield. You can get your men to the ridge line quickly, but they’ll be less effective when they get there and vulnerable to counter attack. Clever Generalship can get your division up on the Pratzen Heights, but you’re piling on the disruption – is it worth it, when a single volley from the enemy could tip you over the edge?

With Disruption comes Rallying, and this happens to be our absolute favourite thing about these rules. There’s so little attention paid in many rule sets to rallying, usually either a binary yes/no, or a number that you tick down in simple increments with activations. In Soldiers of Napoleon, rallying is an ordered process that reflects not just the game mechanic of disruption, but the ways in which Napoleonic units overcame the friction of the battlefield. The action of rallying – in other games passing a leadership test, or removing shock, or pinning or similar – is turned into an active player choice that shapes the battlefield. Rallying requires spending an order card and giving your opponent victory points, with elite troops able to rally using most cards and inexperienced units on far fewer. Rallying can get your men back to combat effectiveness, but it will require giving up on issuing orders elsewhere on the field, and gives your opponent an edge toward victory. You’re always asking if it’s worth it, if you really need those units, how you need them and when.

Once you do rally, there’s a simple series of steps to follow to remove disruption, each representing a different way Napoleonic era units held together under fire or other stress. This is genius, and other games would be well served in adding it to their systems. Not only is it keeping interest and choice in what’s usually the most boring, least interactive part of a game, but it’s exactly how it should be. Sometimes a line unit might withdraw and regroup, or a cavalry squadron might form up around its colours after a swirling melee. Other times, a battered unit needs to stay in place to pin the enemy – the last men of a square holding out against impossible odds, losing men (and capability) but still there to the very last. Choosing these options draws the narrative out of a game very simply and naturally and makes rallying an important, complex decision with real impact on the field.

You don’t reason with Intellectuals

The book and cards themselves are well produced, full colour and well illustrated. Rules, particularly the all important formation rules, are accompanied by well posed model shots, not just to show you how units can and should move, but also to keep that Napoleonic feel suffusing every page. The book really looks fantastic at every point, with full page art spreads to break up sections and hundreds of models from the classic Napoleonic favourites (Perry, Front Rank, Wargames Foundry and others) providing interest and colour.

It isn’t all perfect, however. The background historical content is well written and illustrated, though its inclusion in a fairly advanced rule set is a bit of a puzzle – I’d think most people picking it up would know at least a little about the 100 days campaign, but regardless it’s a pleasant read and it’s hard to tire of reading about those desperate days of the Emperor at bay in 1813-14.

Some issues around layout and rules clarity create some minor problems – rules aren’t always where you’d expect them to be, and one section in particular (scaling distances up and down to play at different miniature scales) provided a bit of a discussion over meaning and intent in Goonhammer towers. But, of all the rules in the book, this one is the least impactful. Where this is the case, the quick reference sheet available via download on the Gripping Beast site, is more than capable of clearing them up.

On the historicals spectrum of “indecipherable layout” to “easy to understand”, Soldiers of Napoleon is firmly on the side of easy, and these minor issues don’t otherwise spoil or hinder learning and playing the system.

Why get this book?

The big question echoing around the wargaming sphere whenever a new Napoleonics ruleset is released is “does this need to happen?”. There are hundreds – if not thousands – of systems covering 1792-1815, many purporting to be the only system you’ll need for the ideal scale of battle it covers. So, overall, why bother with Soldiers of Napoleon?

It’s an interesting, choice-driven system that firmly feels Napoleonic in every way that matters. It challenges players to think about their every action in terms of feeding in to the wider battle, both on the table and the imagined corps or army level engagement they form a part of. The cards provide a unique take on the period which, when added to the attention to detail given to orders, formations, unit types and rallying, naturally draws out the narrative of the ebb and flow of the field. It is a much superior rule set for mass battles at 28-6mm than other popular alternatives like Black Powder and if you’ve been following along with our round table discussions on force selection, deployment and activations, you’ll see that Soldiers of Napoleon approaches many of our favourite ways of designing and playing historicals. If you’re new to Napoleonics at a mass battle scale and want a challenge, particularly if you’ve been playing Sharp Practice and amassed enough troops to go big, this is most definitely the system for you.

That wraps up our review but we have more coverage of Soldiers of Napoleon coming soon, so stick around to see an interview with Warwick Kinrade and see the system put through its paces with a mass battle. In the meantime if you have any questions or feedback, drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com