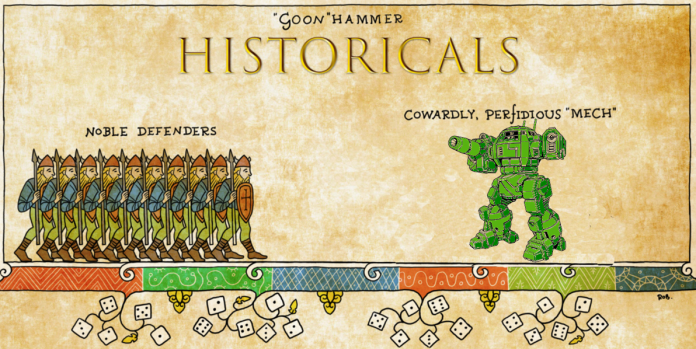

Mechs? In My Historicals? It’s more likely than you think!

Mechs belong in Historicals because the beginning of Mecha culture is 100% certainly, absolutely and uncontrovertibly our domain. We could cite Leonardo Da Vinci’s clockwork knight, Bacon’s terrifying and metaphorical Brazen Head, or the fact that John Dee made a mechanical flying beetle (did he fuck). When it comes down to it though, humanoid Combat Mecha are historical fact, and the earliest one – the terrifying Mechanical Turk – single handedly bringing an end to the Seven Years War before being reconfigured to play chess in 1770. Having discussed and agreed on this absolute historical truth, we’ve unleashed the Historicals team to bring you their increasingly unhinged takes on Mecha week.

Jackie Daytona: If I wasn’t an ordinary human mortal I’d say the sight of that Mechanical Turk back in the day was a sight to behold I’ll tell you. That thing lopped off heads like it was nothing and even the Prussians were shitting their breeches. The damn thing was on their side! I’m glad they ripped out the horns when they made it a chess machine, loud bastard.

Ilor: I’m going to take it a step farther and assert that the Trojan Horse was the earliest documented case of mecha being used in warfare. And super effective, too! It only took one to lead to the destruction of an entire city! Of course the archaeological record points to even earlier uses, and who can say for certain whether or not Wicker Men strode across the British Isles doing battle with one another during the Neolithic Age.

Mecha in Historicals – Konflikt ’47

Getting back to slightly-reality tinged takes, Warlord Games Konflikt 47 really does combine historicals and mecha, taking the miniatures (and rules) for Bolt Action and giving them a weird war 2 twist – tesla and rail weaponry, power armoured infantry, werewolves, giant bears, genetically engineered bull terriers and even rules for Scifi Italians, which is pretty rare. Most importantly, it has mecha – lots and lots of mecha – and after Greg demanded we produce this article, Weird War 2 beckoned.

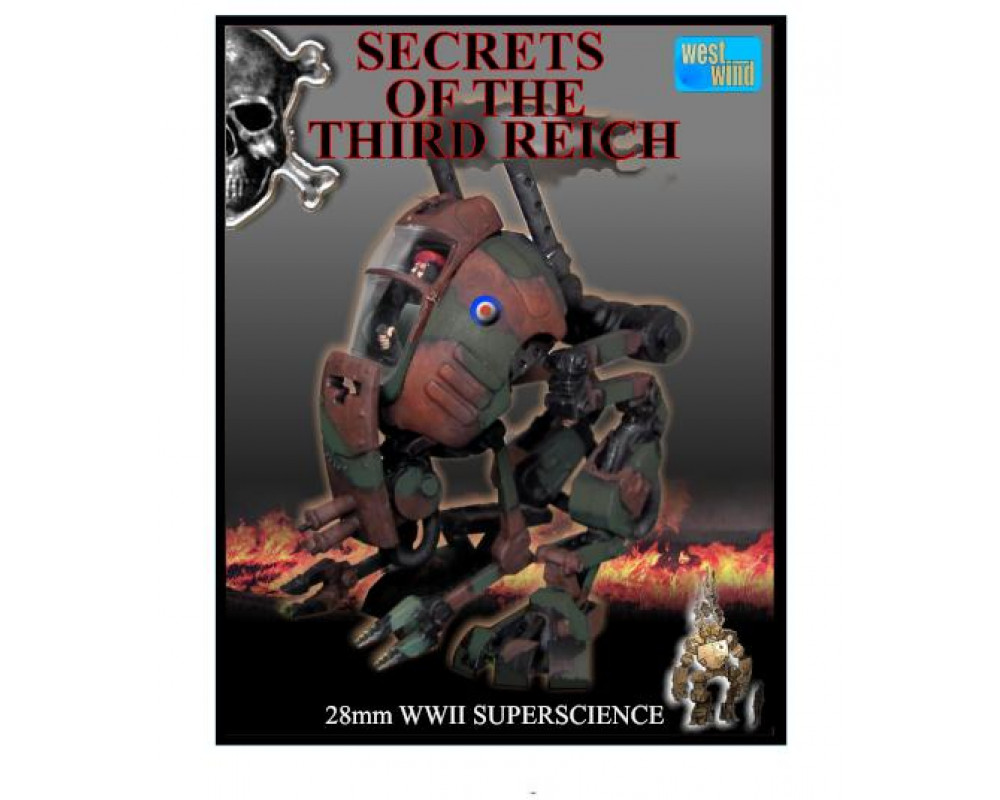

I really do like a good Weird War 2 setting – Wolfenstein, Achtung Cthulhu and all that stuff, so I was pretty primed and ready to go with a Konflikt 47 mech, particularly after reviewing Xenos Rampant which has a very light touch set of suggestions for the period. There’s some fantastic mecha out there for quasi-historicals games, and in prep for this article I did my research and came out with some favourites and recommends. Weird War 2 games come and go with incredible frequency, awesome models and perilously short lifespans. Dust Tactics seems to have been abandoned altogether by Fantasy Flight, despite giving us some fantastic mechs and AT-43 didn’t survive the death of Rackham (though if you want to give it a go, the rules are out there). Those mechs are hard to come by these days, but the lure of the “put a ww2 tank turret on a spider mech” is incredibly strong.

There’s something about that Dieselpunk vibe, that frees up a lot of the bullshit colonialism that Steampunk goes along with and lets you smash giant stompy robots into the greatest monsters humanity has produced (so far). Adding legs and fists to a tank lets you punch Nazis, and really, when it comes down to it, is that not the point of historicals gaming and, indeed, mecha? Historicals mech seem to go down two main routes for Weird War 2. There’s strangely articulated light walkers with front and top heavy vibes that take their design cues from second world war aircraft – the West Wind walker below really reminds me of a Bristol Beaufort, though that might be because I’m not wearing my glasses:

While the other direction is to smack a tank turret on some walker legs to produce some truly terrifying spider-mechs, which this West Wind Productions almost T-34 mecha amply demonstrates:

While the other direction is to smack a tank turret on some walker legs to produce some truly terrifying spider-mechs, which this West Wind Productions almost T-34 mecha amply demonstrates:

Growing up a massive WW2 plane nerd, I wanted to go down the lighter route, so I got the lightest of the available Soviet Mecha to turn my Bolt Action platoon into something that might work for Konflikt ’47. The Cossack Light Walker (looks to me inspired by a Yak-15) is a very very light walker with low armour but surprising speed and agility, something that my otherwise footslogger-heavy Soviet list lacks. Armed with a light autocannon and medium machine gun, it can throw a surprising amount of lead downfield and take out other light vehicles while doing so. The combination of Agile (an additional 90 degree pivot when moving) and Recce (can bugger off in reaction when targeted) means that it’s able to zip out of cover or out of line of sight, get a few shots off and (if your activation order is right) sod off to escape retribution.

When I got this I was slightly dreading the build from a history of bad experiences of metal and resin hybrid minis, but it turned out alright. The resin used for these is pretty easy to superglue, and the ball joints into the legs popped in snugly, so it was just a matter of balancing the pose and keeping it still until the superglue cured. It was a really fun model to paint, and as you can see I weathered the shit out of it and daubed it in a ton of water effects mixed with brown washes to create hideous, liquid mud. I enjoyed it enough that it moved my whole Soviet platoon back up out of the paint queue – I might not get to them immediately, but they (and one day the much bigger brother, the Mastodon Heavy Walker) are very much back on my radar.

HardyRoach: Branching out from Weird War 2 into Weird War One [editors note: more on this soon, folks!], here’s the first recorded implementation of a piloted mech in the British army, the venerable Mk III Campbell. Named after former Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman (who was a noted champion of the value of bipedal mech design in parliamentary appropriation committees) this war machine was manufactured by the Metropolitan Carriage Company in Birmingham, and was designed as an answer to the peculiarities of modern trench warfare during WWI. Mounted atop two hydraulic legs capable of supporting several tons, the Campbell was equipped with a QF 6-pounder Hotchkiss gun and two air-cooled Vickers machine-guns, capable of putting out considerable firepower despite its relatively small frame. The downside of this compact design was a tight and stuffy compartment, with space only for one pilot who was forced to act as both driver and gunner – as such, moving and shooting at once was somewhat off the table.

The Campbell saw only limited use on the western front, as the end of the war came before the first manufacturing run was fully deployed. Despite that, its service continued through the interwar period, and it was given the nickname “Old Soup” for its distinctive tin-can-like shape, or more rarely the “Campbell-Battleman”. Despite more modern tracked war machines being more prominent in the western theatre of WW2, the Campbell found a new lease on life in the east, as its bipedal nature made it perfect for traversing thick jungle terrain in Burma. Suitably camouflaged, the lack of mobility was also not a hindrance, as it could act like a mobile defensive platform, creating hard points where needed.

On a more credible subject: I recently got myself a resin 3D printer, and I’ve been like a kid in a sweet shop with the wide, wide world of STL files. In my searches I found this lad, a Weird War British mech. It was an easy enough print, though the pilot lost a couple of fingers and the top of his gun due to my sloppy support removal. Thankfully I’ve got a spare box of Wargames Atlantic French (watch this space for more on that), so swapped in a pointing hand and a fresh revolver hand. For painting I used airbrushed a deep brown, followed by some khaki highlights. I then sponged on a load of different khaki and beige shades, concentrated around the edges of panels. Finally a bit of sponged on metallics and black soot liquid pigment around the guns and exhaust, and it’s just about done. For the base I originally tried out a cracked desert theme, but it just wasn’t coming together. Instead I used some of the Geek Gaming Scenics battle-ready mixes, some of the Scrublands and the Patchy Plains.

Unprompted, Ilor Talks the History of Battletech

Ilor: Of course no historicals discussion would be complete without some kind of diversion that amounts to “old man yelling at clouds,” so here it this week’s hottest of takes:

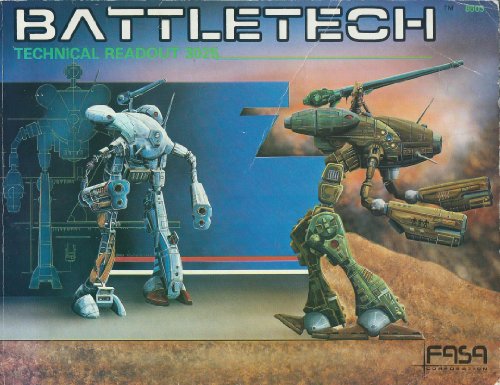

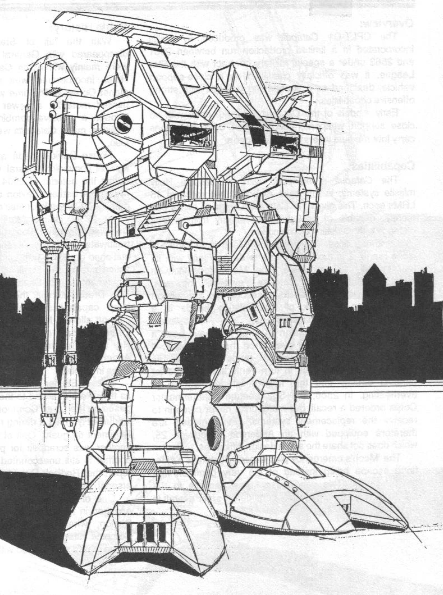

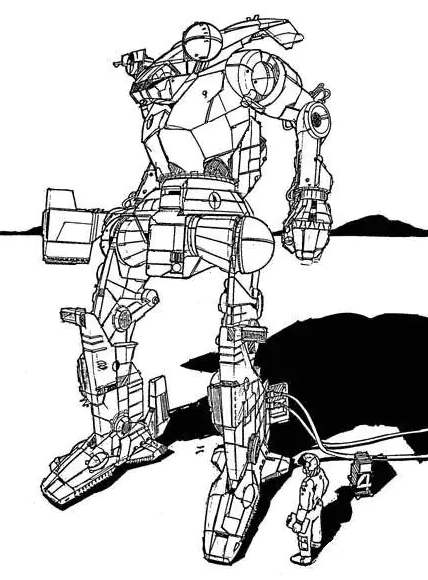

3025 is the pinnacle of BattleTech.

There, I said it. If we want to talk about history, we need to go back to the beginning. For BattleTech as a game, that means going to the original sourcebook for mecha, which was “Technical Readout: 3025” first published in 1986. To 14-year-old me, this book was sheer imagination-fuel. It contained page after page of line-art drawings in the style that would become iconic for the franchise. In addition to the raw stats (armament, speed, armor in various locations, etc) and notes on key variants, the text had all sorts of in-universe details about the mechs themselves. Fun facts, like how the technology to manufacture the lamellar armor on the Marauder had essentially been lost, or how the Rifleman’s top-mounted radar unit made it an ideal anti-aircraft platform. These details didn’t affect game play at all – in the case of the Rifleman as an AA platform AeroTech hadn’t even been released yet – but they provided a ton of color.

Similarly, there were usually a couple of notes about units, pilots, or unique mecha that accompanied each entry, again all presented as in-universe information. While none of this was crucial to the play of the actual game of BattleTech itself, it did a fantastic job of developing the setting, and of giving players ideas to spark their own battles and campaigns. Taken collectively, they reinforced the key trope of the original BattleTech setting – that galaxy was in a dark age, technology had been lost due to constant, senseless warfare, that the Successor States were more than happy to cut off their noses to spite their faces, and that salvage was what kept both House and mercenary lances alike in business.

Now, you can quibble or argue as to whether or not this is realistic. In our own world, periods of prolonged warfare often lead to technological advancement rather than stagnation or regression, but as a sci-fi nod to Europe-after-the-fall-of-Rome it was evocative. Say what you want about its level of realism, it had verisimilitude in spades.

Sadly, FASA never saw a setting that they didn’t want to wreck through advancing a metaplot. I watched them do it to BattleTech, Shadowrun, and Earthdawn, and it was heartbreaking every time. In case you are unfamiliar with the term, “metaplot” means that the storyline of the game setting continues to move as new products are released. Events happen in the game world, events which change fundamental aspects of the setting. Generally speaking, this is done to allow the company to sell more sourcebooks. After all, once you buy everything for a static setting, what else does the publisher have left to sell you? Hence, metaplot.

But think about that for a moment – the company has put a ton of time and effort into coming up with a compelling setting and gotten you hooked, only to pull the rug out from under you and change a bunch of stuff you liked about the setting in the first place. For BattleTech, this was The Clans. Turns out some mercenary whack-job jetted off into deep space and over the course of like a century invented an entirely new society, rediscovered advanced technology, produced a shit-ton of new mechs and weapons, and came crashing back into the Inner Sphere like the proverbial bull. All in complete and perfect isolation. Suddenly Clan Tech was the answer to all of the problems. Can’t make Marauder armor anymore? No worries, the Clans can.

If you wanted more options, more gadgets, more factions, and more complexity (which BattleTech already had in abundance, boy-howdy) then the introduction of the Clans was fantastic. And people who started playing the game after the release of the Clan sourcebooks didn’t even really notice. As far as they were concerned, the Clans had always been a part of the setting. For those of you who have started the game during its most recent resurgence in popularity, I almost certainly sound like a deranged old crank – and you’re not wrong!

But here’s the thing: I don’t play wargames just to push minis around the table and roll dice while I eat Doritos and drink cane-sugar Cream Sodas. I play wargames for the same reason I play RPGs, and that’s to tell a story. I like to “forge my narrative” so to speak. I love the unbridled possibility of a setting, I love how stories unfold as we play individual games or whole campaigns, how WE are the ones changing the setting, how we are making it uniquely ours. And that’s why metaplots suck so badly for me – because they are almost always uniformly less interesting, nuanced, and compelling than the stories we come up with on our own, even if ours is ever only relegated to “head canon.”

Example: the original Shadowrun setting was incredibly cool, but by the release of the “Super Tuesday” supplement the metaplot had devolved to “LOL, let’s elect a dragon to the presidency.” After a certain point, I just stopped buying setting sourcebooks all together because they had increasingly less and less relevance to the “future history” of the games I was running. Similarly, I stopped playing BattleTech because the setting was wrecked and the new mech builds were wildly unbalanced. The game had changed underneath me and I didn’t like what it had become.

Does that mean that people who like BattleTech in its current incarnation are bad and wrong? Yes. Yes, they are.

But no, not really. I am stoked that BattleTech has gained popularity with a whole new crowd of younger gamers recently, and that Catalyst is continuing to support the game. What’s not to love about giant, stompy robots? Sadly, even though it is still very much a product of the 1980s in terms of its rules, the game itself has lost all nostalgia value for me. Occasionally I’ll pull my old Technical Readout: 3025 off the shelf, thumb through it, and reminisce about the minis I painted (badly), the games I played, and the friends I made doing it. But the game itself is just not for me.

So if you come across a crusty grognard in your gaming store who looks over at your shiny BattleTech game and grumbles under their breath, know that we’re not complaining because we’re old. Or not JUST because we’re old.

tl;dr – Stupid clouds!

Well, we did it, the historicals team talked about Mecha. Hopefully you’re happy Greg? We’d love to hear your questions, comments, suggestions about historical mecha and other such strangenesses – and some tips about list building for Konflikt 47 please! – contact@goonhammer.com