We’ve been to the past, we’ve dived into translations, we’ve looked square in the eye of feminist Science Fiction and learnt a lot from the experience, and now we’ve reached a high water mark – the decade that produced some of the greatest Science Fiction works of all time. It’s time to put on the Hendrix, keep one eye on Vietnam and crack open some Harlan Ellison.

This month we’re looking at American 1960s Science Fiction, the much vaunted New Wave. The New Wave brought new approaches, different story telling techniques and sex, drugs and rock and roll to Science Fiction. It’s a bit of a nebulous beginning, initially referring to the early 60s British authors like Brian Aldiss and John Brunner writing intense, socially relevant fiction and storming the US pulp market with these weird things called “books” rather than serialised fiction. From there, it went from strength to strength as SF authors started to include things like “feelings”, “characterisation” and even “women” into stories that were as much about inner futures as they were about rockets and robots. This is when Scifi finally acknowledges that it’s a political, if not revolutionary, act to think and write about the future, and authors pulled in contemporary concerns and freedoms with abandon.

Though it kicked off in the UK, the American New Wave pushed off into it’s own spaces in the later 60s when the increasing focus of magazines like Galaxy on “ordinary people” and the emerging counter-culture movement started to move authors into new and exciting spaces that the Brits hadn’t explored. We’ll come back to the Brits writing stressful novels in the endless grey-and-brown brickwork of Birmingham and London another time, but for now we’re turning on, tuning in and dropping out.

This is the time of Philip K Dick, Robert Heinlein, Frank Herbert and Daniel Keyes. It’s also the time of Star Trek, The Outer Limits and the lingering influence of the Twilight Zone. If the 50s saw Scifi gain mainstream attraction, the 60s saw it firmly lodged in the collective consciousness, never to leave.

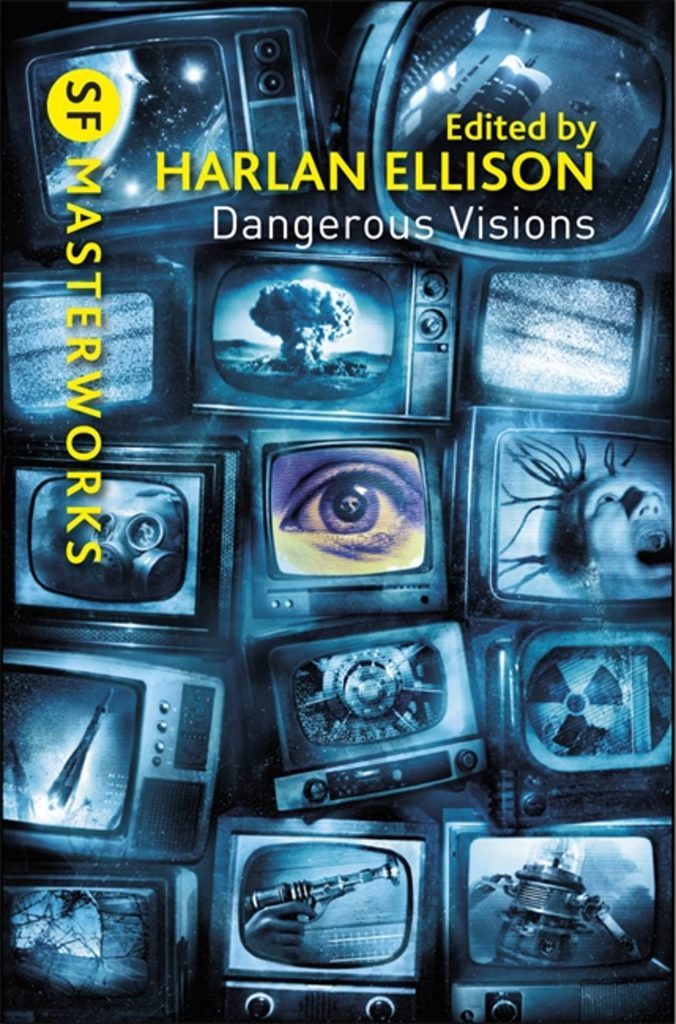

Dangerous Visions, Harlan Ellison

Harlan Ellison is occasionally described as l’enfant terrible of Science Fiction – in the mid 60s a young writer pushing boundaries, destroying idols, writing everything from the grotty body horror of I have No Mouth and I must Scream to all-time-classic Star Trek Episode City on the Edge of Forever. Both are fantastic examples of all that the New Wave had to offer – sex, death, high-concept SF, weird shit – but Ellison’s greatest and best enduring work isn’t really his. Dangerous Visions (1967) is a collection of 33 short stories from a massive range of writers, most of them on the bleeding edge of the Scifi scene at the time. They’re deliberately experimental, boundary-pushing SF, though by the time he’d collected and published all these brand-new stories, the bow of the New Wave had reached out to stranger, and better things.

As a historical document for the development of American science fiction in the two decades following it, it’s an important book. As a collection of great minds writing great things it’s astonishing – PKD, Pohl, Aldiss, Niven, Anderson, Knight, Sturgeon, Lafferty, Zelazny and Delany all feature and you’ll rarely see a greater collection of individual brilliance than that. It belongs in every collection for what it represents alone, regardless of the content of the stories.

Luckily, that content is more or less totally fantastic. I wonder if Ellison gave the writers prompts like “please contain sex” or “feel free to talk about cannibalism” because this is deliberately convention and genre pushing stuff. To us, 55 years later it’s all a little quaint, content you’d see fairly happily on a prestige TV show before the watershed, but at the time it was genuinely transgressive stuff. My favourites are probably Sex and/or Mr Morrison by Carol Emshwiller, (also published in The Start of the End of it All, a collection of Emshwiller’s fiction by the Women’s Press) a weird and uncomfortable story either of desire for an alien or untreated schizophrenia and paraphilia that rewards a reread, and Aye, and Gomorrah by Samuel Delaney where his consistent themes of sexual and gender politics work really well into an exploration of fetishistic sub-cultures amongst spacefaring tourists. Others haven’t aged so well in the light of day – RA Lafferty’s Land of the Great Horses probably read more charitably about Roma peoples in the mid 60s than it does now and Sturgeon hangs a short story on the shock reveal that incest is bad. Ellison’s Prowler at the Edge of the World is just straight up weird, Jack the Ripper obsessed with, and drenched in, misogyny.

It’s a mixed bag but much more on the great than it is on the good (or bad), and certainly worth a read. The road that leads out of the pulps into the modern day – particularly into the world of 80s and 90s cyberpunk – comes straight through Dangerous Visions. The follow up(s) aren’t quite as good, eventually I think everyone trips over the fact that the Enfant Terrible usually grows up to be a difficult to work with Adult Shit.

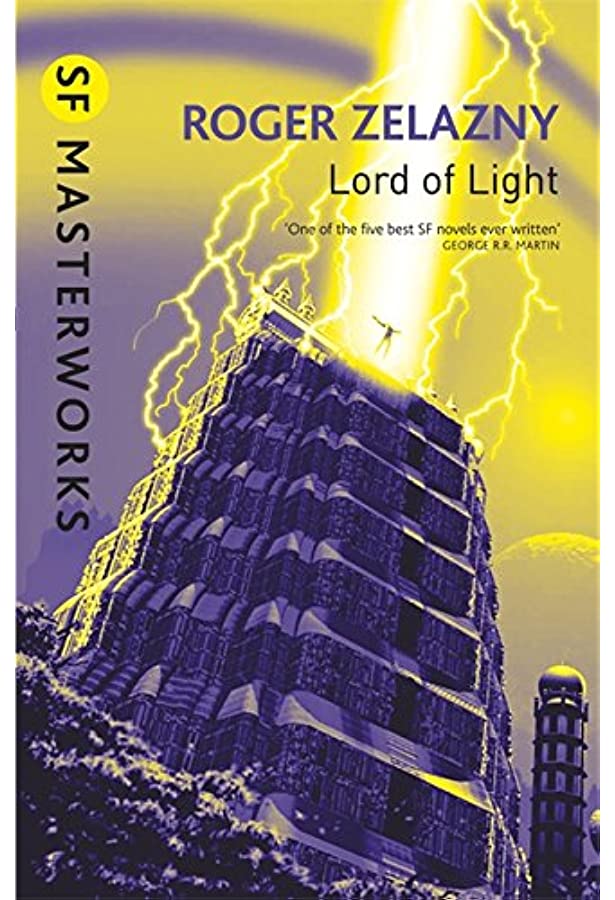

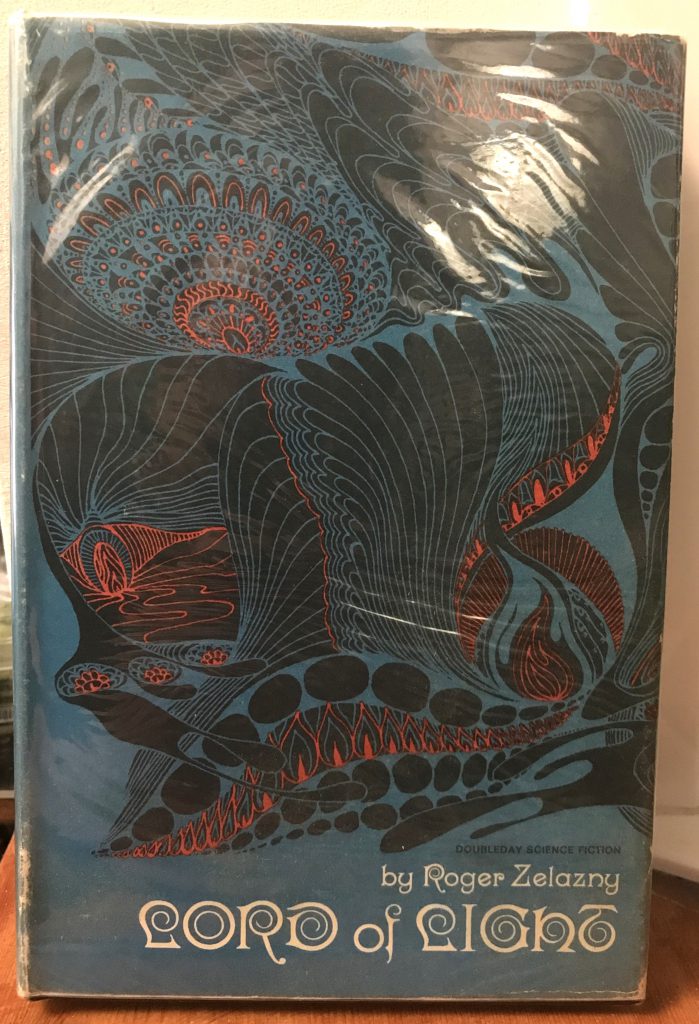

Lord Of Light, Roger Zelazny

The Gods walk the face of the world. From vanished Urath, man has spread across the stars to a new earth where the teeming masses live under the watchful eye of Gods and Heroes. One man sets himself in the face of the Gods. One man, one Siddhartha, Great-Souled One, Sam.

Alright, clear the fucking deck because Lord of Light is the best science fiction novel ever written. Not only is it fantastically written, just the most beautiful prose and perfect pacing as if one of the Gods themselves had put their wisdom to paper, it’s moving, tear-jerking, action-packed and reflective. It delves into characters and pulls out universal truths of the human condition and roots them believably into a fantastical world. It’s a page turner and a head scratcher, both compulsive and puzzling. It was the cover for the Argo plot, but that’s the least interesting thing about it and that it’s best known for that is a damn shame. You’ll read it once, think “wow” and then turn right back to page one to start again. It – and I can barely type Lord of Light as anything other than “It”, the singular book as if no others had ever existed – is everything you would want from a science fiction novel.

I think the first thing author Steve Brust ever said to me was “Let’s have an argument. Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light is the best book anyone’s ever written.” “Ah,” I said, “If you make it best SF book of the 1960s, I’ll go along with it.” “Oh. Fair enough.”

Neil Gaiman

There’s very little I can say about Lord of Light that isn’t in the above (or below) quotes from far wiser minds than mine. In the context of this article, Lord of Light is a perfect introduction to the New Wave before it gets too navel-gazing in the mid 1970s, retaining enough of the conversational is-it-fantasy style of the pulps and the Golden Age while picking up all the interest in character, feeling and story that the New Wave brought to Scifi. Zelazny wrote it intentionally ambiguously between a fantasy novel – and you can pick up Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions to see this kind of fantasy style – and then-contemporary Scifi and retains all the heart, atmosphere and readability of both. In all of his works, Zelazny plays with a lot of modern, fantasy and heroic cliches and in the mix reinvents them all. There’s a little Sam Spade in here, a bit of Raymond Chandler, Robert E Howard, Clarke and Asimov, but it’s all Zelazny and all Sam.

And Sam. Sam most of all, Sam first and last. We have lost Roger, but Sam will always be with us, so long as people are still reading science fiction.

G. R. R. Martin

Yes, it’s undeniably not great that we have an American author playing about with the Hindu gods, particularly when it sets up a guy called Sam against a regressive-tending pantheon, but there’s no white guys here playing hero (there’s only two definitively white-guy-named people in it and one is a villain), and it’s much less of a conflict between religions as it is one within. It is not a novel written about something approximating the Hindu pantheon written by someone with experience of it, but very much one written with the filtered-through-US-culture look at India and Hinduism that suffused the late 60s. For all that the concept is problematic, the content isn’t as much as you might think – there’s nothing signalled as regressive or oppressive about Hinduism or the Hindu Gods, and heroes and villains come from everywhere within the narrative. It arguably strays into orientalist territory at times but it’s never derogatory, meanspirited or suggesting “the west” as superior. That doesn’t make it better – it was weird when the Beatles all decided to play about in that space, and it’s still uncomfortable here, but as an artefact of a very particular 1960s-70s obsession in US culture, it is very much of it’s time. What it achieves from this uncomfortable place is a beautiful work that, in my view, respects the cultures it pillages from, for all that it doesn’t necessarily understand them.

Just fucking read it, alright?

Slaughterhouse Five, Kurt Vonnegut

Billy Pilgrim is an unwilling soldier, prisoner of war, alien abductee, zoo exhibit, father and accidental time traveller. After surviving the destruction of Dresden, he proceeds through life with a fatalistic acceptance – first in the sepia grey of post-war USA, and then on to the planet Tramalfadore, back to the war, forward into the late 60s and through the third world war and the partition of America, whereupon he dies. So it goes.

I don’t know if you can talk about weird 60s scifi without Vonnegut. Not just because his mainstream SF output – especially Sirens of Titan and Cat’s Cradle – forms a really solid body of work pushing the genre out and around the boundaries of the early 60s, but because Slaughterhouse Five showed everyone what you could do with science fiction. Not just autobiographical, not just funny, not just interesting and weird and equipped with a quintessentially Scifi plot, but raw emotion and politics too. Slaughterhouse Five says something that should resonate with everyone on Goonhammer – war is unrelenting, stupid hell that can barely be comprehended let alone played with, or at. Vonnegut, always weird, is at his mind-bending best in Slaughterhouse Five, ripping both us and his protagonist Billy Pilgrim out of linear time and into a startlingly moral mix of Vonnegut’s own experiences surviving the fire bombing of Dresden and time-striding Aliens from Tamalfadore that reflects back on WW2 but came to be one of the all-time statements on the brutality and horror of Vietnam.

It’s a great introduction – and likely the absolute peak – to Vonnegut and his tripped-out fatalism, humour and piercing moral compass that he combines with bizarre characters and seedy porno-drenched Americana in all of his best books. It’s the best window into the series of semi-connected metafictional novels Vonnegut put together that intersect through, with and beyond Slaughterhouse Five – the meditation on the emptiness of fascism in Mother Night, full on evisceration of Capitalism in God Bless you, Mr Rosewater, even back to the trials and sorrows of the Rumfoords in Sirens of Titan. Vonnegut very rarely takes you where you expect to go, but wherever his stories end up, they’re intensely personal, often very funny and dead-on accurate to the absurdity and malice of the world system we’re trapped in, and a meditation on the nature and significance of death and if you think that’s a terrible thing, then you haven’t understood a word I’ve said.

Black Library Pick

I’m going to change up how this works a bit. Rather than adding a fourth classic SF book and pairing it with a Black Library one, I’ll do one that fits in the general theme of the article. If there’s anything to pick up from the massive outpouring of authors and styles in American scifi in the 1960s, I think it’s not just showcasing but valuing new perspectives and ideas.

There’s noone in the Black Library who does this better than Mike Brooks.

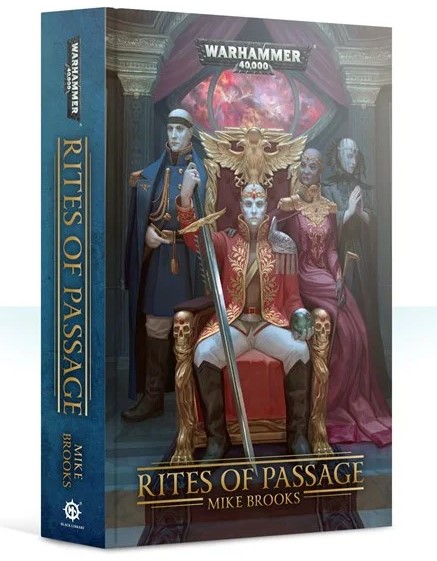

Rites of Passage, Mike Brooks

Rites of Passage is a murder mystery and tale of political skulduggery set in a Navigator House, where betrayal, machiavellian machinations and dynastic power struggles intersect with chaos cultists, warp-drenched schemes and the byzantine internal politics of the Imperium.

Raf wrote a review for Rites of Passage on release in 2019, and I picked it up off the back of that review a couple of months ago. What makes it a fun read is the same that makes it a decidedly new wave novel – Lady Chettamandey Brobantis. Brooks spins the novel off a fantastically strong, intriguing and interesting main character who explores 40k Scifi from a new (valued, absorbing and ascerbic) perspective. Rites is set in a Navigator House, so simply from that we’ve already got a new way of looking at the world both physically (they do have three eyes after all – what more Dangerous Vision could there be than the gaze of the Navigator?), and metaphorically as the Imperium’s most conflicted asset – both immensely valued and valuable, but also hated and feared as mutants. The tension inherent in that position is certainly part of the book, but the real new perspective comes from Chetta.

Chetta is old. That’s a quick little thing to say, but how many 40k protagonists are old? Dante and Yarrick are/were old, impossibly old, but they don’t act it, or think it. Their age is a number attached to their name, it’s glib and surface. Chetta is old – she isn’t lightning quick on her feet, she suffers from painful joints, she uses a cane. What it means to be old in a setting where every other character gets juvenant drugs and appears to be in their mid 40s for 200 years is very rarely explored or even mentioned, but here it is and it’s remarkably unusual to have protagonists that are as grounded in physicality in a Black Library book. There are things Chetta can’t do – not “can do through gritted teeth like an action hero” but can’t do. She exists as a real character in a Scifi world. She has her own internal life and struggles that make her a human(ish) character too. Chetta refuses to be encased in a grav assist chair, or receive the cyborg levels of augmetics she would have in another book, because that’s not her. That’s a very New Wave idea, just the simple concept that someone could have their own motivations, reasoning and emotions in a science fiction context. Chetta is old – she’s also a wife, a mother, a terrifying political opponent, a sarcastic quipper and an extremely astute operator. Hopefully there’s more of her to come.

Questions? Comments? Suggestions? STILL screaming “what about Heinlein?!?”, given that you’d be hard pressed to find anything more 60s than Stranger in a Strange Land? Get in touch contact@goonhammer.com, or leave a comment below and join our Patreon and talk about books, please!