We love Napoleonics. Who doesn’t? Over here at the Goonhammer star fort, we usually play our Napoleonics in semi-skirmish settings, at most using a couple of battalions of foot and squadrons of cavalry. Perhaps you want something bigger. Something grander. Something that will let you refight the largest battles of the era, with whole divisions, whole corps of soldiers clashing over miles and miles of battlefield. If you’re thinking that, you’re in luck – because so is Et Sans Resultat (ESR), now in third edition and ready to take you to very, very big battles.

Before diving in to the review, thanks to David at The Wargaming Company for providing materials for this review.

This review is part one of our reviews of ESR Series three, The Core Rules review. As we publish, you’ll see them appear here.

Et Sans Resultat!

ESR is a perspective-based wargame on a grand scale. It focuses on command and control, on marshalling and deploying your forces to meet their objectives, reacting to the enemy and coordinating your armies to deliver what you need them to do. It’s about prediction and planning, putting you right in Napoleon’s boots as you take on the challenges of strategic and operational warfare.

“Perspective based game” means abstraction enough to not be concerned with individual men, or even individual battalions, and a level of focus on command and control – getting the right orders to your units at the right time, then letting them get on with it – that is often unfamiliar to wargamers. If we put it in the context of other common Napoleonics rule sets, here your job is to coordinate ten games of Black Powder, or a hundred games of Sharp Practice, trusting to your plan (and your subordinate commanders) to not just win you a skirmish or a battle, but a cataclysmic conflict. You’re not just “a” general here, but the real thing – Napoleon, Blucher, Wellington, Kutuzov, one of the many terrible Austrian generals – and it feels like it.

The core rules offer grand scale combat with a near-unique focus on command and control that’s done better than in comparator games working with a similar focus. It’s an intriguing, gripping and rewarding ruleset, but not without challenges that may deter some mini gamers coming at it from skirmish or big-company rule sets.

How ESR works

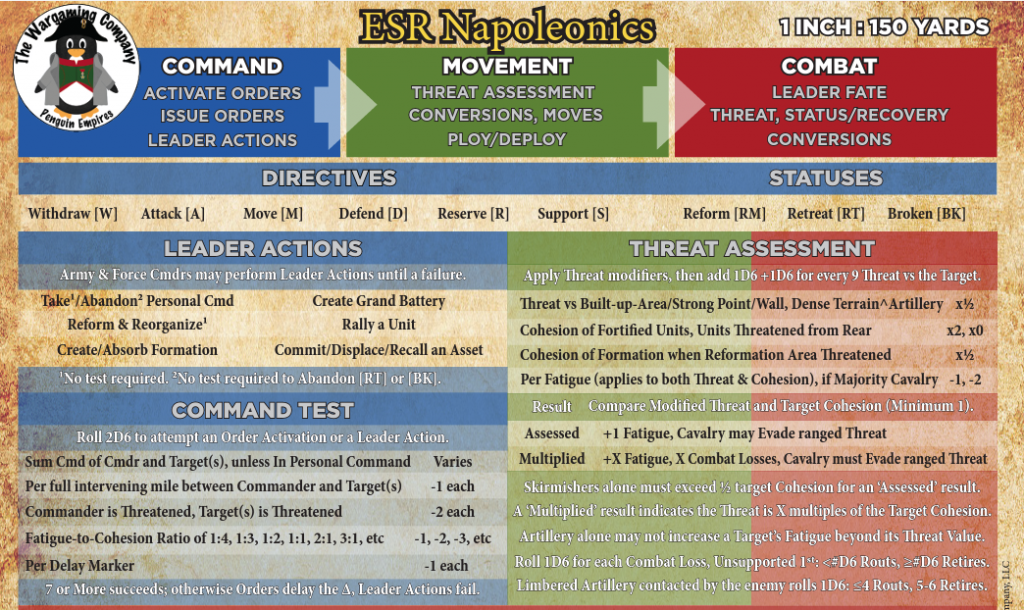

The fascinating thing with ESR, and something that I think the Wargaming Company has done exceptionally well, is that this is a wargame about perspective. You, the player, take the role of Army or Corps commanders – Napoleon or one of his Marshals – and your role is to issue objectives and set stances that determine how your divisions approach those objectives. You’re not rolling to see if a musket hits, or if a unit makes a charge, because that is beneath you. You are telling the Generals and Colonels beneath you what to do, and it’s up to them to do it.

That’s a massive perspective shift for wargamers like us (Zuul and Lenoon) who are more used to 28mm gaming. The majority of the rules in the book are setup to enable your divisions to move autonomously. They will gain their objectives through switching their statuses and directives via orders – Withdraw, Attack, Move, Support, Defend, – but their actions within these conditions are determined by the rules of the game. They’ll move, encounter enemies, resolve combats and withdraw according to the maths and rules laid out – operating autonomously, but always under your command. You’ll issue your orders and watch as your soldiers try to pull them off according to their abilities. You will be to blame if things go wrong, because your men will fight to the best of their ability, each time.

This fascinated me (Lenoon) as I started reading it, because it’s such a hard thing to do. There are so many variables on the battlefield that make automated miniature gaming difficult to pull off, but it’s been pulled off here. The possibilities and edge cases that could derail it all are not only covered in passing, but programmed into the game. The clever bit that unlocks this is the conversions mechanic. Each status and directive programmes units to do different things (like move, or close for attack, or hunker down once an objective is achieved) as they approach objectives. Conversions allow – and force – formations to switch between statuses and directives, perhaps forcing a mauled division into retreat, or an over-eager cavalry wing to recklessly charge forward and then reel back after the charge. As a result, this isn’t the kind of predictable, chess-like feel that some large scale games can end up with. Chaos and friction is here, and your enemy can frustrate your plans, forcing you to reassess, replan, redeploy or even, Marshal Ney-like, take direct command of a formation and force it to carry out your plan at bayonet point.

It’s genuinely a brilliant system, and the care and thought put into these mechanics that allow formations to act semi-autonomously is evident on every page. The vast, vast majority of the rules revolve around this, with others relating to command, orders and how combat and damage/fatigue works – simple, streamlined systems there too – creating a well-thought-through barely constrained chaos that feels as exciting, challenging and occasionally frustrating (in a good way!) that command and control must have been on the Napoleonic battlefield. When I was playing my (slightly ridiculous looking) test games with post-its as sadly I don’t (yet – see the ESR model reviews later this month) have the models needed to play this properly, I had a blast.

I sent men out to secure a couple of biographies of napoleon, and others to drive post-it Russians off a high hill. The Infantry hunkered down to provide cover for my columns, and then stubbornly refused to have their directive and objective changed for a couple of turns. With me unwisely committing reinforcements to column to move them up quicker, I underestimated how long it would take to deploy into line – and this allowed the Russians to bring their entire force to bear against my deployed division. It was a close run thing, until Russia brought some cavalry around and, while I was able to throw my cavalry in to rack up the fatigue on the main Russian division, those smugly atop the hill managed to stave off further assaults – after that, the French were routed, and Napoleon (me) was left aghast, scrambling to throw reserves in too little, too late. Even with post-its and books as hills on this tiny board, it felt operational. When it clicked with me how it was all supposed to work, it really, really worked, and provides a fantastic, unique and indeed compelling gaming experience.

Fighting Battles

The fighting aspect of ESR is arranged through the Threat system, which is one of the best-written sections of the rules. Simple and clear to work out, your formations will exert “threat” out at range (or in contact) to represent combat. Units coming into range of each other will check threat in both movement and combat phases. In the movement phase, Infantry and Artillery pile on threat, and in the combat phase cavalry do too – a neat way of dealing with fire, hand to hand and skirmishing. Threatening units add to enemy fatigue, with each formation having a cohesion value that amounts to how much damage they can take and remain perfectly operational. Too much threat and whole formations may convert to withdraw, perhaps routing, breaking or losing units. In practice this is a very simple system, and the diagrams provided are helpful in clarifying how it operates. It adds to the command and control feeling that, the majority of the time, you’re either pushing formations back or forcing them to withdraw, rather than picking up units off the board.

Fatigue also comes into commanding units. You switch directives and issue commands through a straightforward command test system, with increasing penalties depending on how much fatigue a formation has, or the distance between commander and formation (amongst other penalties). It’s more nuanced than Black Powder’s “roll against leadership” approach, and interacts well with a delay system that represents all the difficulties of the period when “getting an order to your line” involved a man, a horse, and some flags. It could all go right, and your formations deploy into attack just at the right time – or, with a delay, you could find them marching in the wrong direction, sitting tight on an objective and refusing to march to the sound of the guns (do you hear that, Grouchy?), in which case, saddle up your horse because you’re going to have to take personal command.

The systems involving fighting, command and movement are all very simple, and that’s a real strength of the ruleset. If you’re getting started, a formation or two moving around, converting between directives and being shouted at by Commanders will give you a good game, and the quick start guide will go far. Diving into the rest of the ruleset requires some more work, and that’s where the challenges come in.

Challenges

Unfortunately, there’s a couple of bits about the ruleset that means you have to put a fair bit of work in to get to that point. I wouldn’t class the rules as particularly beginner friendly, both in terms of beginners to gaming and to Napoleonics. That’s ok – not everything should be – but occasionally “complex” strays out of “complex but clear” into “complex and obtuse”. The Threat system and assessing threat is great, but wording isn’t always clear and it took a few reads to work out how and when you were assessing threat, and what that meant for your units. Equally, Conversions – the meat and veg of the semi-automated division behaviour – are simple in practice but complex on paper. You’re checking to see if a division has met a threshold to convert from Move or Attack into Defend or Withdraw. The tables covering this are a little harder to interpret than they could be – something like Lion Rampant’s excellent activation flowchart would be a welcome support for understanding how the system is supposed to work.

Turn order is a good example of both the vision of ESR and some of its challenges. It’s designed as a simultaneous game, both generals moving, assessing threat, taking casualties and issuing orders at the same time according to directive priority (withdrawing units ahead of attacking ones for example). One one hand this is very cool – the battle isn’t a static thing, the kind of static that even an alternate unit activation system builds into the game. When all units on the board have been ordered, moved, converted into new stances, the turn is over and everyone starts again. For a swirling, reactive and proactive game, this is a pretty great idea! On the other hand, it’s tough to actually work that out – it’s not explicitly written into the game – or at least if it is, I couldn’t see it, and, practically, you’re going to want to see what your opponent is doing as much as you’re seeing it yourself. So as a vision the turn order system is really interesting and suits the theme and period well. In practice (with me at least) it ends up a little fiddly – perhaps a GM or umpire would help to resolve it.

Ground Scale is another area where you can see the game is aimed squarely at those familiar with some of the quirks of Historicals – and particularly those who know the imperial system like the back of their hand. It’s a scale agnostic game, so there’s always some fiddling when games try for multiple scales, but in not settling on a single scale and telling people to work it out, I ended up confused on some fairly basic things. In fairness, the game is very clear – recommending for example 150-200 yards per inch for 6mm models. That’s great! Except then most measurements for scenarios and map sizes are given in miles and deployment measures are given in yards. A table might be 4 miles square, coherency between units is less than 225 yards. Ok – so for me (young enough to be a metric boy), I’m thinking right that’s a 4ish foot board and 1 inch ish for coherency. Again, all fine, but then you’re faced with another yards measurement (900 yards coherency with reformation area, for example) and you have to do the maths again. Other systems have slightly more elegant ways of doing this – I’m fond of anything that uses “base width” for example – though I have recently discovered the quick play guides come in different ground scales, which, had I known when doing my practice games would have helped me get over my basic maths problems much quicker!

While the writing is sometimes a little denser than I’d like, leading me to spend serious time puzzling out how a division of infantry (formation) is different to division of infantry (attachment), the Wargaming Company have an exceptionally active presence on Facebook and, during the time we’ve been working on the review, whenever anyone has posed a question to the designers, it’s been answered, clearly and effectively, within hours. While some of the more basic questions (how many infantry bases in a division?) could have been answered clearly and categorically in the book, it is really delightful that if you do have issues with anything, David will provide you with an answer – and encouragement! – very quickly. There’s also a great amount of support on the ESR website, which goes a long way towards solving any issues you might face.

Putting it together

The core rulebook is significantly more than rules, and this is an area where the Wargaming Company have really pulled out all the stops. While the rules may assume a certain familiarity with Napoleonic concepts, the rest of the book doesn’t, giving you a full run through of the Napoleonic wars in Europe from revolution to Waterloo and a surprisingly comprehensive glossary for common Napoleonic terms. A core rulebook of 100 pages spending the first 40 talking about the period is pretty rare in Historicals, which often assume you’re going to get your reading somewhere else. It’s a nice addition to the rules, and sets the canvas well for the massive battles you’ll be fighting.

That canvas will be fought over by your forces, and example army lists for each major combatant – Austria, France, Russia, Britain, Prussia and Spain are supplied, with some of the most clear rules in the game as to how you build up an army. Formations, required units, attachments and reinforcements give you a fair bit of freedom in army composition while keeping things to a fair degree of historical. Unsurprisingly given the depth of information presented in the History section, formations are different in different time periods – a French Revolutionary force will look significantly different to a Late war one. The lists provided aren’t exhaustive – the French examples are limited to infantry divisions, but they will get you started, and attached cavalry and artillery units are present in all Divisions (as they should be!).

In keeping with our theme of “you kind of have to know your stuff here” all of the lists are presented with the national terminology. For the Brits, that’s nice and easy, and French is easy enough (Lenoon: for me at least), but you’ll have to work out what the Russian ones mean – Grenaderskaya is simple enough to puzzle out, but Kirasirskaya (Cuirassier – Heavy Calvary) and Legkaya (light infantry) needed a translation (Zuul: this part was extremely hard for me and I found it a little frustrating).

To help you get fighting, the book also contains 13 scenarios based on battles from the period. The scenarios definitely speak to the rule set as both a passion project and one that assumes you’re fairly familiar with how things should run, because they’re each a single page, with objectives, a massive map and a list of forces. They’re very “real” – objectives are never secure table quarters or do some kind of gamey action, but speak to the nature of the scenario. You may be attempting to evade contact and exit the area via roads as your enemy closes, or fighting over significant strong points, or trying to take an area of high ground. It’s not about killing the enemy (well, unless that’s the victory objective), but about carrying out what your army is there to do. It really adheres to the core concept of the game. You are not a line officer. You’re not even a Colonel. You are Napoleon (or his lesser enemies) – what you’re trying to do is win a war, not a battle.

This is a great spirit, but the practicalities of playing these scenarios are tricky, unless you have a club, group, or regular opponent where you can talk over layouts and objectives. This is real “handshakes and good game” territory where every game is a narrative battle, and that is fantastic in my book (Lenoon), but is a difficult cliff to climb if you’re picking up ESR from other wargames.

Conclusion

This big question we ended up on was who are we recommending this game to? That came down to some different perspectives between us, so here we’ll fully split the review.

Lenoon:

I’d recommend this game to you if you have experience in Napoleonics – at whatever scale – and you want to “upgrade” to grand scale, or you’re anyone (Napoleonics experience not necessary) who is looking for something seriously different than what they’re used to. The learning curve is a little higher than other games, and there are issues around rules clarity if you’re coming over from Warhammer, but I really want you, (yes, you!) to try this game out.

Because the thing is, this is the kind of game I want to be playing. It feels Napoleonic, really putting you in the driving seat of entire corps. It’s a system I really, really, want to play extensively. The barriers to entry are higher than in other, smaller, systems, but once you get over them I really believe the core system will reward you hugely and prove suited to fast, intricate and exciting play. If you have a group that will engage with it, or use the Wargaming Company’s handy map to find one, this will be a staple game, providing all the groggy fun you’ve been looking for and the idea of getting down to it with a regular group is exciting – cannot wait! The ideas are magnificent, much of the execution is excellent and what the game could provide is unique. You have to put the work in to get there, but that’s the point – Et Sans Resultant will deliver results.

Zuul:

This game is absolutely not for the faint of heart. The Napoleonic Wars are a large, complex historical subject with multiple external and internal factors and tons of nuance. This game reflects that in the format and the style. The complexity and difficulty is by no means a knock on the game, it’s rather a reflection of my ability as a player. I’m a relatively new player to Napoleonics and I can’t say I’d recommend this for players similar to myself. The scale and complexity, especially when combined with the deep well of knowledge around units and uniforms, is certainly the deep end of the gaming pool. That being said, I completely agree with Lenoon in saying that this is the game to aspire to. This is Napoleonic Wars at the scale and grandeur it deserves and should be played at.

If you’d like to pick up ESR, you can do so from The Wargaming Company and via distributors around the world. Look out for more ESR content over the next few weeks.

Questions, comments, suggestions? contact@goonhammer.com or leave a comment below,