The game begins with the universe being destroyed, and then you move forward from there, on a loop.

Loop Hero is not really an idle game, as it’s been somewhat curiously — and a bit frustratingly — tagged. You will have to pay attention to it constantly, or you will lose badly and gain next to nothing. At the same time it’s not really a clicker, and it’s certainly not a standard RPG of any sort; you have no control over your character’s actions, which are always the same: move forward and attack.

No, if anything, Loop Hero is a board game, something like the card game Dominion grafted onto an infinite runner. The basic gameplay flow is that when you begin a run, a track is generated of random dimensions that always constitutes the same number of tiles, forming a loop. Your character begins at a campfire and starts moving around the loop (either clockwise or counterclockwise, arbitrarily) and fighting the enemies that spawn in front of him in combats that could generously be compared to autochess but most closely resemble what happens when you just mash the attack option while hitting the turbo button on an emulated JRPG. The main conflict and damage relationships in the game are all in these combats; monsters respawn every “morning” (there’s a timer that tracks a day/night cycle whose main function is putting more baddies on the map) and get harder in difficulty once you pass your campfire, completing a loop and beginning another one.

When presented with these fights, your little guy either wins and continues or loses and dies; he almost always wins, because this is a game designed to kill you and end your run one of two ways: by attrition, overwhelming you with a bunch of little encounters that are just in aggregate a bit too hard for you to overcome with your current perks and gear, or more commonly, with hard face-check powerful enemies — occasionally these can be buffed groups of common enemies coming right after you complete a loop and level them up, but they’re almost always personified as the boss of the run. There are three bosses in the game (at least so far as I’ve unlocked, and there doesn’t seem to be space on the UI for another so if there is one he’s the final boss), and each represents higher difficulty conditions imposed on the loop with higher rewards: enemies get more and more special abilities which make them much harder to kill, but you get better and better loot progression. Each also more directly represents a really hard special fight that spawns…once you engage with the game’s secondary run-based mechanic: the cards.

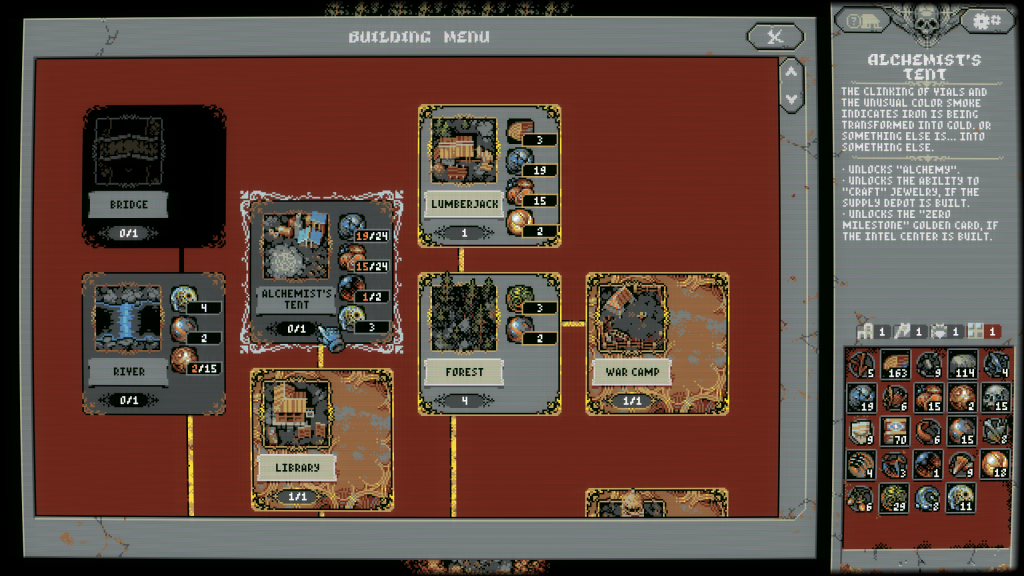

This is where the true board game feeling comes in. You put together a deck of cards, divided into four categories, and each of which can be placed on one of three tile locations: road cards that can be placed directly on the loop itself (usually things like “Grove” or “Village”) that your Loop Hero will pass over every run; building cards that go adjacent to the loop tiles, either inside of or outside of the loop (“Vampire Mansion” or “Outpost”) that modify what happens on the loop tiles themselves; land cards that go on any free non-loop adjacent space on the board and modify your hero’s overall stats for this run (“Mountain” or “Forest”); and specialty cards that operate in wildly different, usually unique ways, like “Oblivion” which allows you to destroy any card you’ve placed on the board or “Treasury” which pays out a huge chunk of metagame resources when you surround it with eight land cards. Then there are the uniques on the bottom right of the deck-building screen, which give you a special one-time use only card that significantly changes the mechanics of how your run works — “Arsenal” gives you an extra equipment slot, which actually changes how the three classes each play significantly; “Ancestral Crypt” gives you a single resurrection to full health from death each run, but no more bonus health from equipping armor (unsurprisingly, the Necromancer maybe gets the most out of this, but the Fighter can do good business with it as well).

The other big variable in each run is which character class you choose for the Loop Hero himself; the Fighter starts out unlocked and you get access to the Rogue and Necromancer later on. Each plays significantly differently in expected ways — one’s a tank, one’s a glass cannon, one’s a summoner — and you need to construct your deck differently for each class not just to take advantage of synergies, but avoid outright conflicts; the Outpost, for example, helps out Fighters and Rogues who wander by them, but will fight you if you’re a Necromancer. Which makes sense, because you’re a Necromancer, come on. Frankly the Fighter doesn’t have much use for the Outpost either, though, because as a price of their help, the Outpost soldiers take all the good loot; only the Rogue, who trades trophies in at the end of each loop for equipment rather than relying on in-loop drops, gets the full benefit of their help with none of the downsides.

Then there’s the massive meta-game that revolves around building a town using the resources you get from each of your runs. Some of this stuff is cool, and the art of the various villagers is especially flavorful and neat, but this is where Loop Hero becomes, quite intentionally, a bit of a grind. If you die in a run, you only return with 30% of what you gathered. If you intentionally leave a run anywhere but your campfire, you only return with 60%. If you leave a run after defeating the boss or returning to your campfire at the end of the loop (functionally the same thing, as the boss always spawns on top of your campfire), then you can depart with the full 100%. This is complicated by the fact that you’re not collecting the materials you need themselves, but shards of the materials that combine at certain thresholds to make one unit of the full thing — 12 sticks turn into one stack of actual lumber, for instance.

High resource thresholds for building things, the two-tiered resource system, and the amount of stuff you lose on bailing from a run or dying…can lead to some long grinding. This is especially true if you don’t immediately cotton to the fact that certain resources come from certain card choices, as expressed as enemy loot and tile rewards. You eventually get access to an in-game glossary that demystifies some of this…but you have to unlock the glossary itself around halfway up the progression tree, and it’s still pretty vague in places. Most runs will end up in places where they’re long on basic progression resources like food and lumber and short on high-end resources like all the various magic orbs, and there is at the top of the tree an Alchemist who will exchange some of those…but you have to grind out some of those magic orbs first. All in all, you’re looking at about ten to twelve hours or so before you’ve unlocked most of the stuff in the game, assuming you’re going in blind and not with a guide to help maximize and plan out resource aggregation. And that’s fine, it’s good for a game like this to take awhile to master — but hours eight through ten or so can get to feeling really bad, like you’re not making any progress whatsoever. Maybe there’s a little bit of fine-tuning that should have been done there — a couple more cards handed out a bit earlier to add variety to the slog when you can easily beat the second boss but are still trying to get your first clear against the third. Or maybe you should just wiki exactly what’s going on under the hood with the cards, and thereby get good. It’s a delicate balance, and while I’m not sure they got it right, it doesn’t ruin the game.

Final Verdict:

There’s plans for DLC once Four Quarters is done with their bug-fix/UI patch process, and the game could use maybe a little bit more content than it has right now for that extra five to ten dollars or so; it’s not that there’s not much here — there certainly is, and the loop is engaging enough to keep you at it if you really enjoy it until you’ve filled out your entire town and are going for personal bests on numbers of loops in a run and such. But it’s a $15 game for a reason, and $15 is a perfectly acceptable price to pay for a week’s worth of entertainment.

Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.