Last year’s stacked lineup of games for the Game Awards had us thinking: What was the best year in gaming? As part of our series on determining gaming’s best year, we’re putting together an article on each year, charting the major releases and developments of the year, and talking about both their impact and what made them great.

The Year: 1979

We are now in the golden age of arcade games. Space Invaders continues its second year of dominance and a host of innovative space shooters pop up attempting to capitalize on its success, giving us some of the best arcade games ever made, Asteroids and Galaxian the biggest among them. Despite owning the home console market with the Atari VCS (known today as the 2600), Atari was struggling without a “killer app” to move the console and under increased pressure from its parent company, Warner Communications, who refused to credit game developers publicly or pay them bonus pay for working on successful games. After deciding they’d had enough, four of Atari’s top programmers left to found Activision in 1979, and they immediately set to work making third-party titles for the Atari 2600.

Internal disagreements over whether it was time to build a new console in the face of competition ultimately led to the ousting of CEO Nolan Bushnell, who opted to focus on building out a series of children’s pizza restaurants known as Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theatre after buying the rights to the chain back from Atari. Bushnell had founded the restaurant in 1977 with a single location in California as a long-time passion project. After leaving Atari in 1979 he’d add seven more locations and continue to expand the operation through franchisees.

On the tabletop side, TSR released the final book in its trilogy for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, launched two years earlier – the Dungeon Master’s Guide. The guide here is most notable for going extremely hard on its cover art, featuring a sick red demon which would ultimately clash with the company’s frantic efforts to remove such imagery from the game as the growing Satanic Panic combined with an all-time bad movie adaptation put pressure on the company to take action. The book covered the basic game rules for running a campaign and keeping players in line, with lots of charts and tables for monsters and loot, and came with a Dungeon Master’s screen for hiding key rolls from players (before cackling with sadistic glee, of course).

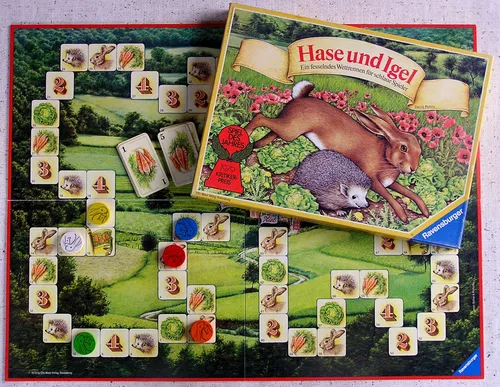

First Spiel des Jahres Awarded

After being founded in 1978 the first Spiel des Jahres was awarded one year later, and racing board game Hare & Tortoise was the award’s first winner. As the award has done for countless titles over the years, it transformed Hare & Tortoise into a perennial seller that remains in print today both as Hare & Tortoise (Ravensburger) and as Around the World in 80 Days (iello).

NEC PC-8001 Releases

Nippon Electric Company (NEC) released the first model of its PC-8000 series line of personal computers in May 1979, introducing the first Japanese PCs to the market. The PC-8001 was a smash hit in Japan and over the next two years would come to represent nearly half of the Japanese PC market. The success of the 8000 series would fuel NEC’s growth over the next decade and they’d go on to develop the first digital signal processor, dominate the Japanese computer industry, and ultimately compete with Nintendo and Sega during the console wars with their PC-Engine/TurboGrafx-16 console.

Atari’s Third Wave of 2600 Games Hit Shelves

Atari’s third wave of games for its VCS console were released in 1979, this time across two waves: The first eight games in March and an additional three games in September and November that year. For the most part these games featured digital translations of table games in Casino or Backgammon or sports games in Bowling, Football, or Miniature Golf. They were all mostly fine, with the real stand-out of the bunch being Video Chess, but they showcased a growing issue with the 2600 console: Atari still lacked the dominant, top-of-market, culturally-impactful mega-hit that they needed to sell the console and drive widespread adoption of the home console.

Video Chess

One of the most revolutionary titles on the Atari VCS was, ironically enough, 1979’s Video Chess. The first game to use Atari’s new 4kb game cartridge, Video Chess had to clear more than a few hurdles during development, such as the fact that the Atari VCS could only display 3 to 6 sprites on a given line depending on programming. The end result was a game which cost more than average thanks to its improved chipset but gave Atari VCS owners a true digital chess experience, complete with a playable AI and full support for all the game’s moves.

Ozma Wars

Japanese developer SNK’s first successful arcade game, Ozma Wars is a top-down space shooter (the game approximates vertical scrolling with a moving starfield background) in which players command a ship and shoot down enemy spacecraft and asteroids while managing a constantly dwindling energy reserve. While technically a monochrome conversion kit for Taito’s Space Invaders, it’s recognizably different as a game in most respects and has four distinct levels with different enemies to go up against, giving it quite a bit of additional replay value.

Monaco GP

This vertically-scrolling arcade racing game features a variable width and surface track (featuring ice and gravel) and other cars to avoid, with colorful graphics that marked it out at the time despite being one of Sega’s final TTL games. It also featured a deluxe cabinet with a full driving seat, stick shift, steering wheel, and pedal, which helped to make it a hit at arcades. It’s a fun game and an interesting footnote for Sega, who would go on to become the industry leader for innovation in arcade racing games over the next two decades.

Tail Gunner

This vector-based first-person shooter hit arcades in November 1979, putting players in the gunner seat at the rear of a spacecraft which was definitely legally distinct from the Millennium Falcon. Tail Gunner wasn’t a particularly complex game, but it was relatively innovative for the time and fun to play.

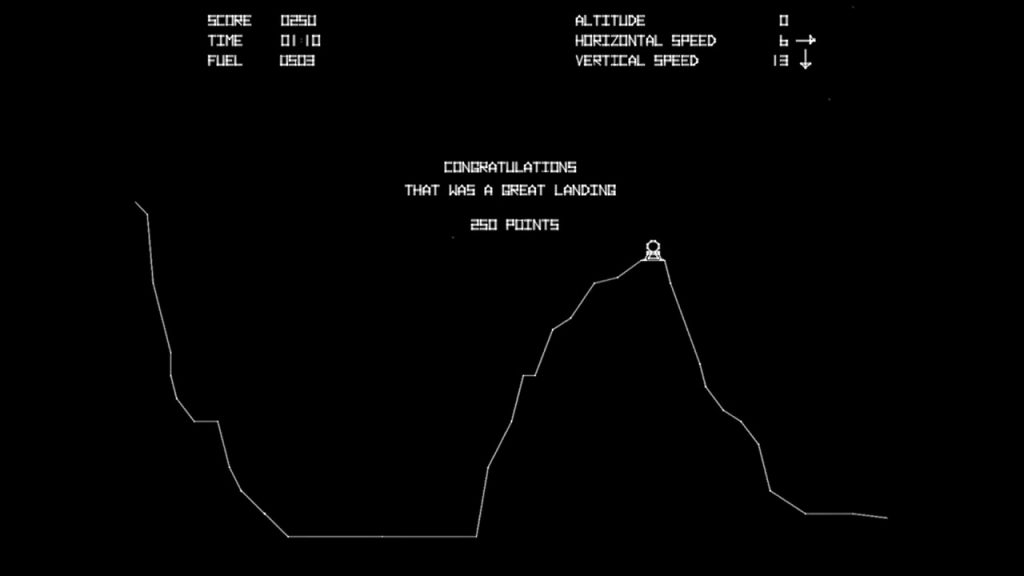

Lunar Lander

Lunar Lander, Atari’s first vector-based game, was released in August 1979 and quickly forgotten in the massive wake left by Asteroids. In the game, players control a descending lunar lander trying to land on the lunar surface below while managing fuel, speed, and gravity with a limited amount of time. The game was a success for Atari and would go on to be copied and cloned a ton of times on home systems and personal computers.

Astro Fighter

This top-down vertical space shooter was the breakout hit for Data East in 1979, pitting players against multiple waves of full-color space enemies, with five different types to shoot down. While very similar to Space Invaders and Ozma Wars, the game adds full color to the mix as well as randomized enemy patterns to make things more interesting. The game was a major success in the United States and part of the wave of games attempting to piggyback off the success of Space Invaders.

Asteroids

Atari’s biggest game of 1979 was Asteroids, a top-down, vector-based space shooter released to arcades in November. Players take on the role of an arrowhead-shaped ship shooting down asteroids and enemy ships in an increasingly hectic playing field as those asteroids break into smaller, dangerous chunks and the enemy ships shoot back. It’s an incredible game with tons of replay value thanks to the randomness of enemies and asteroids. Despite being monochrome, Asteroids was a massive hit, finally dislodging Space Invaders from the top of the sales charts and becoming the face of video games in mainstream culture at the time. It’s an all-timer and one of the most important games ever released.

One of Asteroid’s biggest features was being among the first games to track a high score and allow players to input their initials (an idea pioneered by 1978’s Star Fire), a practice which would become widespread and then eventually all but mandatory for all arcade releases.

Space Invaders Part II

One year after its first Space Invaders stormed arcades worldwide Taito released Space Invaders II, an updated sequel to the original. This second iteration featured upgraded, full-color graphics and some cute animated cutscenes at the end of each level, plus levels which increased in difficulty, starting invaders closer to the bottom of the level each time and adding new enemies, with different sizes and enemies which could split upon being hit. The game wouldn’t see mass production until 1980 but ultimately the game is a far superior version to the original, though it’s more of an upgrade than an entirely new game.

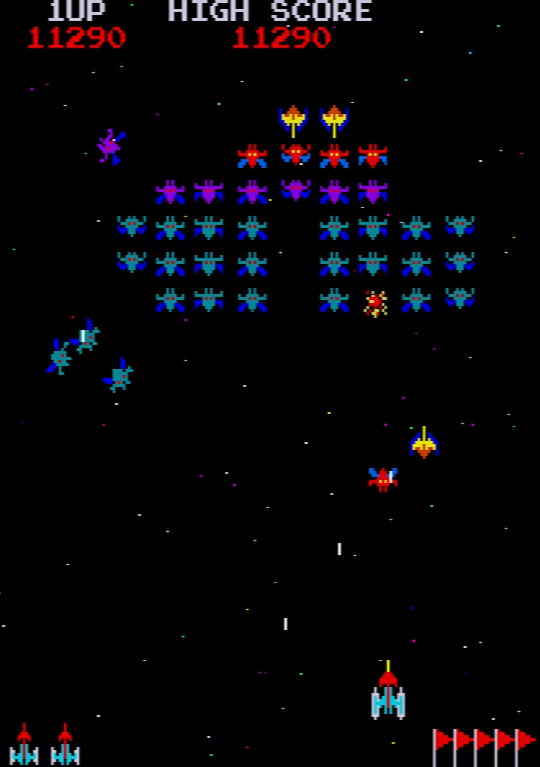

Galaxian

Namco’s attempt at a top-down space shooter, Galaxian was released in Japanese arcades in September 1979 and two months later in the United States. The game was a massive step up graphically from its competitors: While very similar to Space Invaders in that it featured a grid of sideways-moving, descending alien ships to be shot, alien ships in Galaxian would break formation and attempt to dive-bomb the player, rejoining the fleet from behind after they disappeared off-screen. This gimmick came with a price, however; due to hardware limitations your ship could only fire one bullet on screen at a time. The game ramped up the difficulty as play progressed into later stages and the game featured some truly unique hardware which was ahead of its time. Galaxian was very successful on release and would go on to be a massive hit the following year. It would also kickstart one of gaming’s oldest franchises and its sequel, Galaga, is one of the all-time great games.

Hare and Tortoise

Raf: In Hare & Tortoise players take on the role of the Hare and must attempt to speed their way to the finish line.

The track is a simple straight line, however it has some wrinkles to its space layout. The first is that Tortoise Spaces pepper the track; no player’s Hare token can stop on a Tortoise space. You’re also restricted from sharing a space with other players. Alone this wouldn’t make Hare & Tortoise feel special but it’s the actual movement that gives this simple game its edge. Each player begins the game with a handful of carrot cards that must be spent to move along the track. Moving 1 space costs 1 carrot, but moving 2 spaces costs 3, moving 3 spaces jumps to 6, and so on. The faster you go the more cards you’ll burn.

In order to replenish your staff you’ll have to move backwards to a tortoise space, stop on a lettuce space and “eat” one of the lettuce cards you begin with, or take a calculated risk. Scattered across the track are numbered spaces. If you begin your turn in a numbered space that matches your position in the race, you’ll get 10 times your position in carrot cards. Like the lettuce spaces this can provide an accelerant to those players further back in the race though your opponent’s can conspire to ensure you do not receive the bonus…if it is advantageous to them.

This simple game play leads to tense situations where players are balancing a couple of different considerations. While the decisions aren’t particularly deep, they do branch which helps this game punch above its weight (and can unfortunately contribute to some analysis paralysis as players follow the branching mathematical pathways). Hare & Tortoise certainly holds up these days. While it’s simple, simple isn’t always bad. The Spiel has always valued approachable games and it’s clear how Hare & Tortoise earned its award.

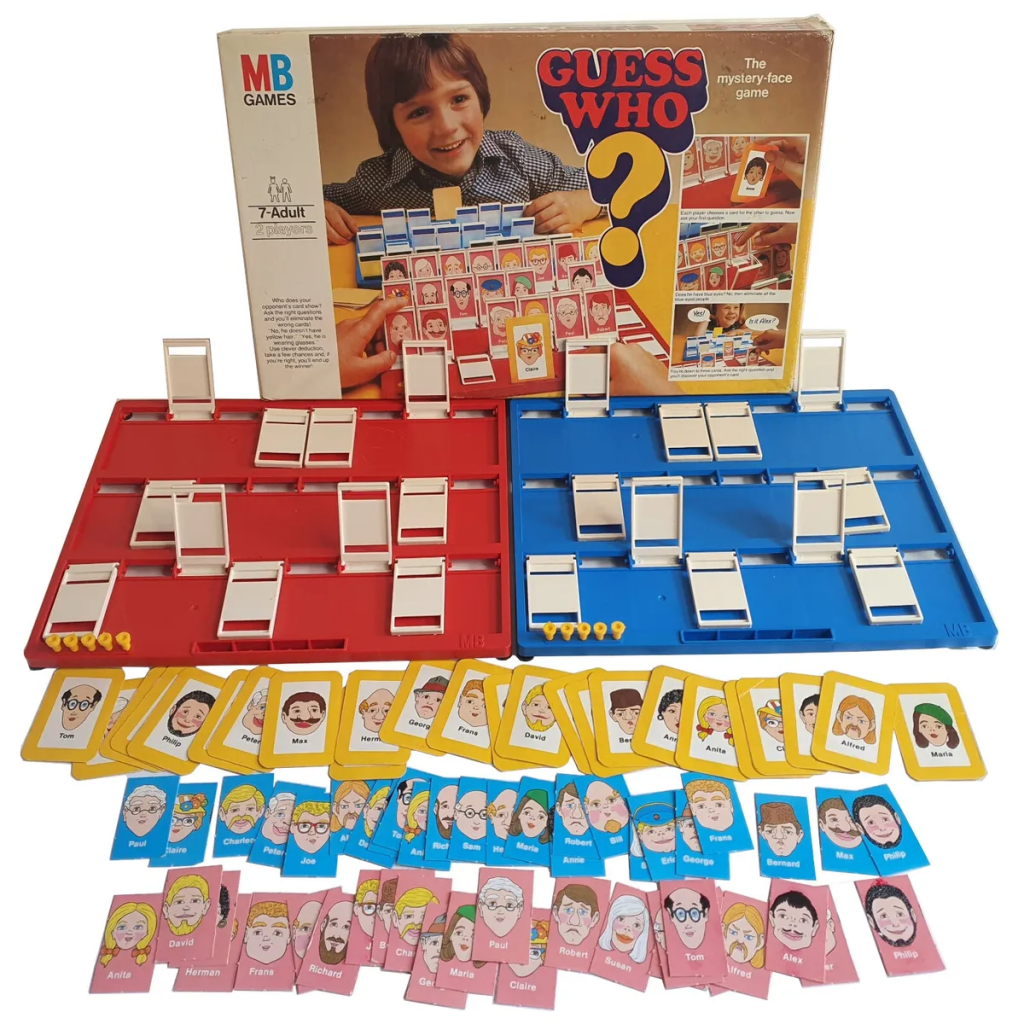

Guess Who?

Milton Bradley published this identity guessing game in 1979. Each player sets up a board of potential suspects and then randomly draws a person for their opponent to guess. Players then alternate asking yes or no questions about the other player’s person such as “do they wear glasses?” and “do they have a mustache?”, eliminating candidates based on the opponent’s answer, with the goal of being the first player to correctly guess the opponent’s person. It’s a fun game for kids, but one that adults will quickly find ways to solve. The original version has its issues – such as only having five women and treating gender like a characteristic – but it’s a fun version of the 20 questions game formula.

Cathedral

This two-player strategy game was designed by Robert Moore and published in 1979. The game starts with one player placing the game’s cathedral on a 10×10 gridded board, after which players alternate placing buildings of their color, attempting to close off areas and claim territory and use as many of their pieces as possible. Claiming areas removes opposing pieces trapped within them, sending them back to an opponent’s hand. At the end of the round, players score points for each building they still hold, and the goal is to have the lowest score possible. Cathedral is a fun, strategically-challenging game with an evocative design. It’s absolutely an underappreciated gem, but one that’s been receiving a bit more attention with recent publications.

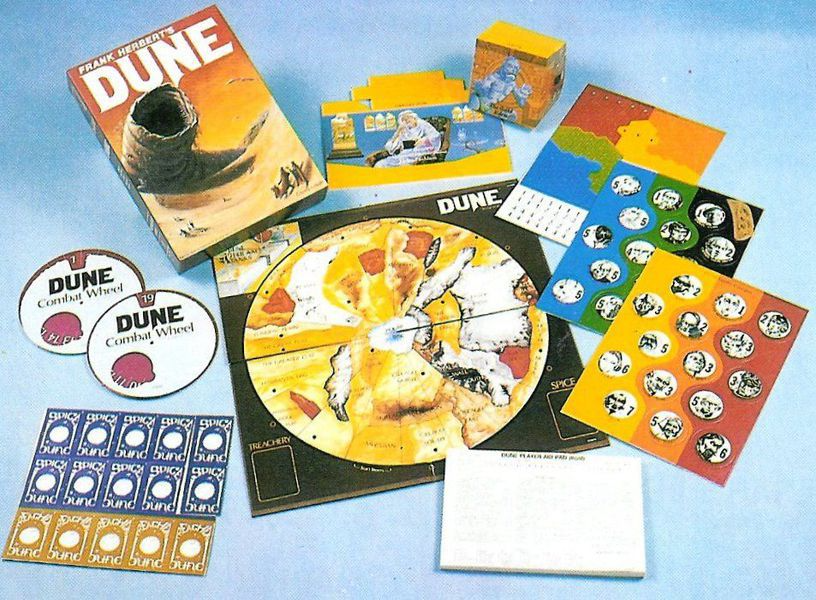

Dune

Frank Herbert’s novel is filled with factions, armed conflict, and political intrigue, and so it’s no surprise that there’d be game adaptations of the series’ universe. Avalon Hill’s 1979 Dune board game is a strategy game in which players take on the role of one of the warring factions vying for control of Arrakis, mining spice, storing power, and avoiding storms as they attempt to outmaneuver each other and claim the planet’s strongholds. Alliances are common (and coalition victories possible), and each faction has its own unique rules and powers (you can go past the standard Atreides/Harkonnen set to play the Fremen, Emperor, Spacing Guild, or Bene Gesserit). The game was well received on launch and recently received a timely reprint from Avalon Hill in 2019.

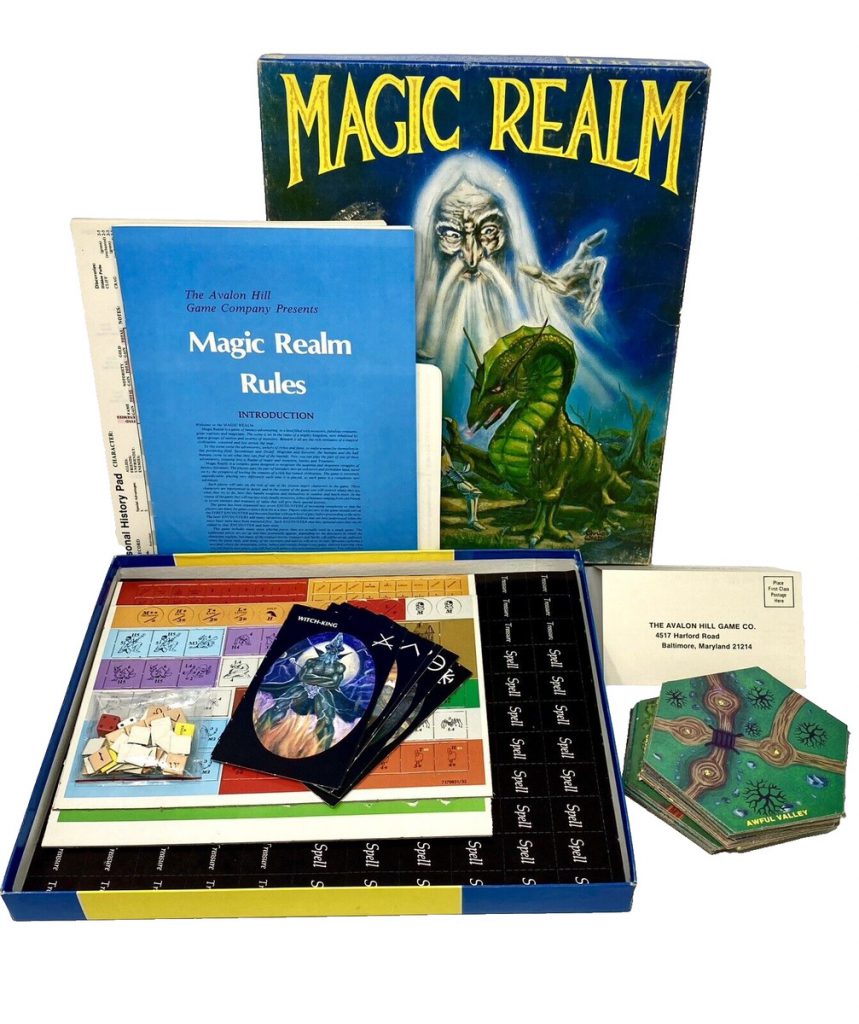

Avalon Hill’s Magic Realm

Magic Realm isn’t the first attempt to turn complicated tabletop RPGs into a board game, but it’s probably the first to get it right. Each game takes place on a large map made of hex tiles, filled with dungeons, traps, monsters, and key locations to explore. Players take the role of one of 16 different adventurers, each with different abilities, equipment, and spells. The party starts at the inn and sets out to explore mountains, caves, and forests on a map that’s randomly generated each game. Players have individual victory conditions to accomplish they can choose before the game starts, and the first player to accomplish their goal wins. Magic Realm is a complicated game, and there’s a ton of randomness in it. It’s a difficult game with a long set-up, but it’s also a great in-between for players who want some roleplaying and adventuring without going full D&D. Magic Realm’s second edition improved on the game substantially and it was enough of a cult hit that when it went out of print in 1998, dedicated fans created an unofficial third edition.

Why It Was the Best Year in Gaming

1979 is a bit of a dark horse in our set, lacking the kind of powerhouse home console release or tabletop RPG we’d see in preceding and following years. But if you look closely you’ll see some phenomenal arcade games – Asteroids and Galaxian are true all-timers, and Ozma Wars, Monaco GP, and Astro Fighter are no slouches, either. There was a ton of innovation at arcades that year as microprocessor games became the standard and companies started to produce the first full-color games for market, creating games that look more and more like modern games (or at least games from the 80s). Galaxian is the true vanguard here, and its sequel would go on to be one of, if not the most successful arcade games of all time. But the original is pretty great and perfectly playable as well. For Atari’s part, Asteroids is another Mount Rushmore-level entry into the gaming annals, and while it was a commercial flop in Japan, it was big enough in the US to dethrone Space Invaders. It’s also great, hectic shooter fun.

On the board game front Hare & Tortoise very much earned its Spiel des Jahres, while Dune and Cathedral both can make cases for being underappreciated classics of their time. It’s a downbeat year with a number of surprisingly polished gems in the mix.

This article is part of a larger series on the best year in gaming. For more years, click this link. Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.