Last year’s stacked lineup of games for the Game Awards had us thinking: What was the best year in gaming? As part of our series on determining gaming’s best year, we’re putting together an article on each year, charting the major releases and developments of the year, and talking about both their impact and what made them great.

The Year: 1983

1983 is the year I was born. It was also the year videogames nearly died*. There are two trends we have to talk about here, both thematically-related but not necessarily causally-related:

The End of the Golden Age of Arcades

Arcades have died multiple deaths in the United States but the first was by far the more devastating. The golden age of arcade games – that period in the late 70s to early 80s – saw a tremendous expansion in the number of arcades in the United States, but as the nascent home console gaming market grew, their influence and profitability began to decline, ending a four-year streak of massive growth. Arcades didn’t die – that wouldn’t happen for another decade and a half or so – but they’d definitely peaked. The Golden Age of Arcade Games had a massive, lasting impact on video games as we know them: Not only was it responsible for the rise of Japanese developers, who were among the most successful arcade companies of the era, but as many of the most popular console games of the 80s would be ports of popular arcade games, the design sensibilities of those games would inform many of the console games released during the third and fourth generations of hardware.

The Video Game Crash of 1983

While sales of home video game consoles were exploding, the games themselves had some real issues, primarily with quality. By the end of 1982 the market had become flooded with not just consoles – most notably the Atari 2600 but also the Magnavox Odyssey 2, the Intellivision, ColecoVision, Vectrex, and Bally Astrocade – but also poor-quality games. Many of these were billed as arcade ports, but what that actually meant varied wildly based on the limitations of the hardware. Consumers by and large had no way of knowing what a game would look like prior to purchase, leading to some massive disappointments such as the Atari 2600 port of Pac-Man, released in April 1982. This all came to a head with the now legendary flop of the Atari 2600 game E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, which released in time for Christmas of 1982 and was so terribly, horrifically bad that it managed to land itself on many “worst game of all time” lists. The rushed game was massively overproduced, leading to Atari dumping truckloads of unopened boxes into a landfill in New Mexico to be destroyed and encased in cement.

At the same time, home computers were exploding in popularity. Inexpensive home computers had hit the market around five years prior and were continuing to drop in price and the Commodore 64, released in late 1982, had dropped in price to $300 by mid-1983 during a price war with Texas Instruments. The Commodore 64 would go on to sell two million units in 1983 and another three million in 1984. These devices were much more versatile than video game consoles and more powerful to boot. Combine cratering consumer confidence in consoles with the rise of a solid alternative, and you have all the makings of a crash. Industry leader Atari, Inc. would post losses of more than $530 million in 1983, starting a long decline that would see the company being sold by parent company Warner Communications the following year.

*It’s worth noting the asterisk here, as these trends – the death of arcades and the crash of the video game market – refer almost exclusively to video games in the United States. They were much less a factor in Japan, where higher population densities and less reliance on driving made arcades more viable for longer periods and the home console market wouldn’t take off until the first Japanese consoles were launched late in 1983. Likewise, the Japanese computer market was still essentially two years behind the US market with lower adoption rates for home computers until later in the 1980s. The arcade market in Japan wouldn’t start its decline until later, peaking four years later in 1986.

Nintendo vs. Universal

1983 saw the swift conclusion of one of the most important legal cases ever brought in the game industry. The story itself is incredibly fun to read and worth retelling in its own future article, but the short version is this: Universal Studios president Sidney Sheinberg wanted to get into the video game business and saw lawsuits as a key way to do that. He’d concluded that Nintendo had infringed upon Universal’s King Kong IP with the wildly successful Donkey Kong and wanted to strongarm Nintendo and Coleco into both paying royalties to Universal and doing future business with the company through a series of lawsuits. Nintendo didn’t budge, and Universal sued.

In doing research for the case Nintendo’s lawyers, Howard Lincoln and John Kirby, would discover that Universal did not own the rights to King Kong and instead had recently won a court case by proving King Kong was in the public domain – doing so in order to create a remake of the original film. During this case it was also revealed that Universal had openly claimed they viewed lawsuits as a profit center when threatening Nintendo. The court ruled that even if Universal had owned the rights Nintendo wouldn’t have infringed on them, awarding Nintendo damages to the tune of 1.8 million. Other companies previously strongarmed by Universal started filing suit shortly after. The case would lead to Howard Lincoln being named senior Vice President of Nintendo while John Kirby was given a Sailboat he named Donkey Kong. The character Kirby would later be named after him.

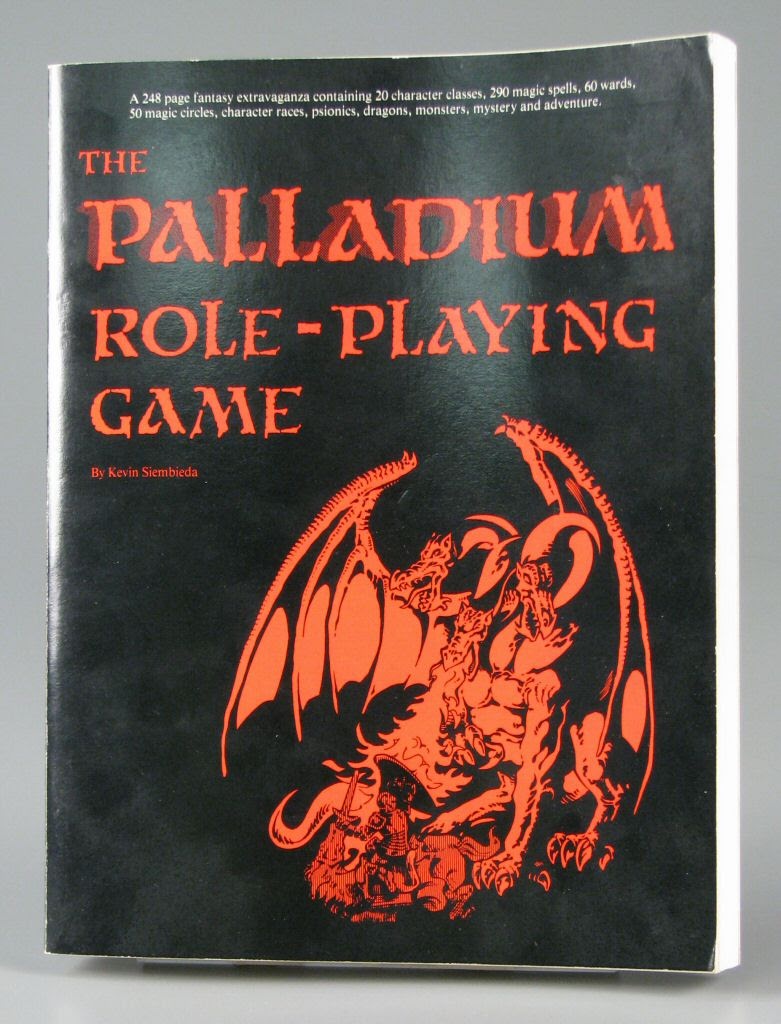

Palladium Fantasy Role-Playing Game

The late-70s success of Dungeons & Dragons led to a host of imitators. In 1981 a pair of D&D players named Kevin Siembieda and Eric Wujcik founded Palladium Books, and in 1983 they released the first edition of their own entry into the genre, Palladium Fantasy Role-Playing Game. The game itself is very similar to D&D, though in several key ways more complicated, giving players a greater number of races to choose from – such as Wolfen, Ogres, Changelings, and Goblins – and eight characteristics to work with: Speed, Physical Strength, Physical Prowess, Physical Endurance, Physical Beauty, Mental Affinity, Mental Endurance, and IQ (gross). Stats still generally functioned like D&D, giving a bonus for having a 16+. Palladium also has an alignment system, though it’s one that works a bit more descriptively and gives players more guidance on how a character of that alignment actually behaves: if you were wondering what kind of vibes Palladium has, the alignment section opens with a paragraph explaining why the concept of being truly neutral is dumb.

While there are a lot of combat rules in Palladium – it’s a complicated game that includes damage to armor and parrying attacks – it’s not the only thing going on with the game. Characters in Palladium have a ton of skills and players in Palladium gain XP for killing things but also for coming up with clever ideas – even if they don’t work – performing skills (successful or not), avoiding unnecessary violence, putting themselves in danger to help others, and yes, for killing monsters. Building a character in Palladium can take an absurd amount of time, especially by modern standards, but it gives you very detailed characters with strong narrative hooks.

Palladium’s first edition isn’t the best version of the game, but it’s a great example of an early competitor to Dungeons & Dragons starting to move away from some of the worse ideas which would become calcified in the D&D ruleset over the next two decades. Palladium comes across as a more roleplaying-oriented version of Dungeons & Dragons, with better tools for creating interesting characters and doing more than just fighting.

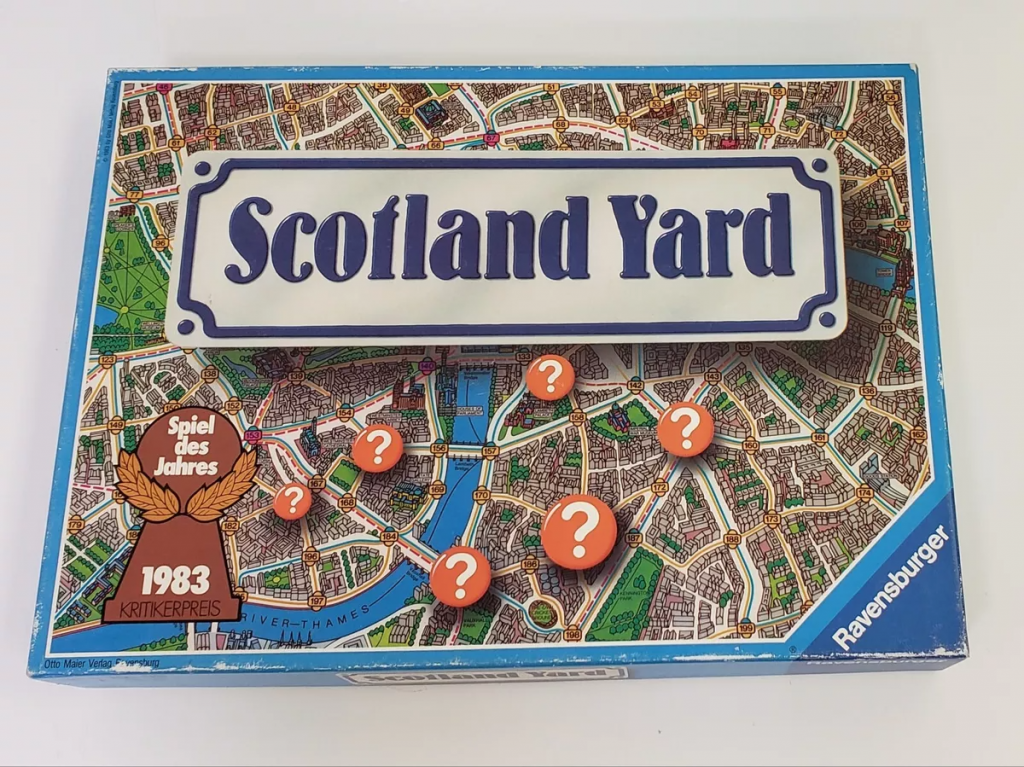

Scotland Yard

The Spiel des Jahres winner for 1983, Scotland Yard still holds up today. We wrote about it a few years ago when we did our March Madness article on Spiel des Jahres winners:

Raf Cordero: Who hasn’t wanted to be a detective at some point during their lives? Scotland Yard is an asymmetric game with hidden information that lets a team of players work together to track the diabolical criminal known only as “Mr. X” through the streets of London. The pitch is simple: each turn, the detectives move their pawns around the city to one of the nearly 200 spaces on the board. If they either land in the fugitive’s space or trap them so they have no legal moves, they win. The detectives move by spending one of three kinds of “tickets”: taxis (which can move to adjacent spaces), busses that move more than one space (but usually not far); and the Underground, which allows players to make large jumps across the map. Meanwhile, the criminal is also moving around, (usually) following the same rules with one major exception: rather than putting their pawn on the board, the criminal writes down which numbered space tp which they traveled, then covers it with the type of ticket they used. In other words, while the detectives may not know exactly where their quarry is, they can make some educated guesses based on the methods of travel used by the villain.

There are, of course, a few wrinkles here. First, a few times over the course of the game, the criminal player has to “surface” momentarily and reveal where they are for one turn. To counter this, the fugitive has two tricks up their sleeve: a pair of ‘2x’ tokens and 5 ‘black tickets.’ The 2x tokens do exactly what they say: they let the villain player move twice in a row, following all the normal rules. The black tickets can be used one of two ways: either to take a trip on a ferry down the Thames, moving in a way the detectives can’t replicate or, more deviously, making any of the normal moves without revealing what mode of transportation they used. Either of these can be incredibly frustrating for the detectives to deal with, and a particularly elusive fugitive can use both at once to utterly confound the constabulary. Then again, use them at the wrong time and you might just wind up cornering yourself in your desperate attempt to escape.

Scotland Yard is not a complicated game, at least not until you get about halfway through and everyone at the table is poring over the board intently, the detectives looking desperately for clues while the fugitive panics in an attempt to get away. There’s a lot here to wrap your head around, but the complexity won’t be found in the rulebook or on the board – it’s in the air between you and the other players as you work out what your plan will be for the turn.

If Scotland Yard has a weakness, it’s that it can fall apart if your Mr. X player doesn’t have a great poker face – the easier they are to read as the net closes in, the quicker things come to a head. On balance, though, that can be its own kind of fun, and rotating who’s on the run can create a completely different experience as different players tend to use the tools available to them in different ways. If you’re looking for an easy to pick up game for a battle of wits between you and 2-5 of your closest friends, Scotland Yard still holds up.

Talisman: The Magical Quest Game

Really old fans of Games Workshop will immediately recognize this game, which sees players move around a three-ring board as they travel from the outer to the inner regions collecting gold and upgrades in an attempt to capture the mythical Crown of Command. Each player starts by picking one of the game’s heroes, each with different attributes. As you move around the board, you’ll encounter and defeat monsters, upgrade your character, and claim a talisman to allow you passage to the game’s innermost ring.

In its base format, Talisman is a fun compromise between running a dungeon crawl style one-off DnD session and playing a board game. It takes a long time to play – usually 2-3 hours – but doesn’t have as much fiddly set-up as you’d expect from a fantasy game with that kind of time commitment. It has a fun, breezy style with lots of goofiness – you’ll often get turned into a frog – but can help scratch that questing itch. The third edition of the game would dramatically improve the mechanics and presentation but the original is still a perfectly fun time.

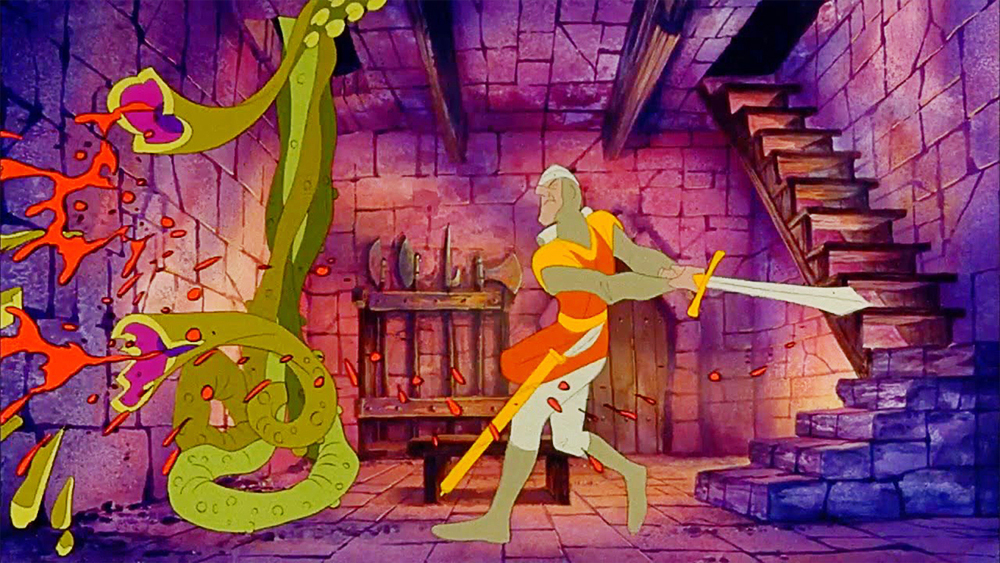

Dragon’s Lair

In 1979 Don Bluth, fed up with Disney after a number of creative differences that arose during the production of the 1981 film The Fox and the Hound, left Disney to start his own animation studio, Don Bluth Productions along with nearly a dozen of his fellow Disney animators. Although the studio is probably better known for its first feature-length film The Secret of NIMH, their second major project was creating the animation for the 1983 video game Dragon’s Lair, a game which pioneered both the FMV genre and the concept of quicktime events in games.

Run off a LaserDisc (you can kind of think of a LaserDisc as a DVD the size of a dinner plate), Dragon’s Lair saw players controlling Dirk the Daring, a brave knight attempting to brave a dangerous castle, slay the dragon and save his beloved princes Daphne. You move from room to room, get a prompt to press a button or a direction, and if you get it right quickly, you live. Otherwise, you die. It’s not a complicated game – a full run-through only takes about 12 minutes – but it is a game where you’re likely to die often.

As a game, Dragon’s Lair is basically one big long Quick-Time Event, albeit one that looks like a Don Bluth cartoon. What you really have to understand about Dragon’s Lair is that it was insanely ahead of its time visually. Compared to games like Pac-Man, Mario Bros., and Spy Hunter, Dragons’ Lair looked amazing – like you were playing a movie – and captivated players. Even now it looks great, and while the novelty wears off after a play or two, it’s still an important game and a fun one to revisit.

Mario Bros.

No not that Mario – you’re thinking of Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros., which would release two years later. Mario Bros. first introduced the world to the Italian plumbers who would take the video game world by storm. This much more simple arcade platformer has players working together to clear screens of enemies each round, racking up high scores. And that’s basically it – round starts, you kill enemies, you move on. There’s a POW block, and enemies you knock over have to be stepped on to finish them off, but otherwise there isn’t much in the way of levels or platforming.

That said, the game itself is very well executed and a ton of fun to play – so much so that Nintendo would bring the game back to serve as the bonus game mode in Super Mario Bros. 3 five years later.

Pole Position II

The sequel to the incredibly successful 1982 original, Pole Position II expands on the original by giving players the option of four tracks to race on and improves the graphics and courses a bit. Released as a conversion kit for the original Pole Position, this game and its predecessor basically invented the racing game genre and Pole Position II would go on to become the highest-grossing arcade game of 1984 after narrowly losing out to the original Pole Position in its release year. The biggest thing the games brought to the genre was having to actually manage turns and drive on a track – something lacking in Sega’s Turbo where changes in track geometry were purely cosmetic. The game is just great arcade racing fun, looks great, and holds up better than most older arcade games.

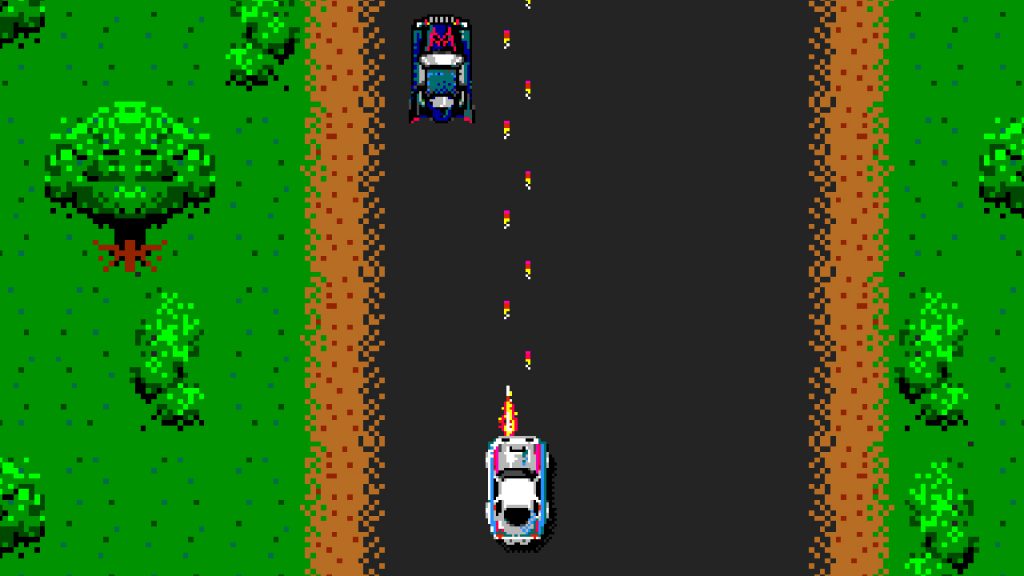

Spy Hunter

1982 and 1983 were landmark years for car and racing games, and Midway’s Spy Hunter was a major part of that. Inspired by the fast cars and action of James Bond films, Spy Hunter sees players taking on the role of driver in an experimental sports car and charged with tracking down and destroying enemy vehicles while avoiding civilian vehicles on the road and using gadgets to evade enemies. It’s a fun, high-speed game that provides a ton of challenge with remarkably varied environments and levels, adding helicopters and boat action. Part racing game, part vertical scrolling shooter, Spy Hunter is still a good time.

Lode Runner

Released by Broderbund in 1983 for the Apple II, Commodore 64, IBM PC, and some of the Atari platforms, Lode Runner is a 2D puzzle-platform game that sees players running around a map collecting gold pieces while evading enemies, armed only with the ability to create temporary holes in which enemies can be trapped. Collect all the gold coins, and a ladder will show up to advance you to the next screen.

Lode Runner sold very well and was immediately one of the best games available for its home computer platforms. It would go on to get multiple ports, including an arcade port the following year licensed by Irem and a Famicom/NES port licensed by Hudson Soft. It’s one of, if not the best, puzzle games released for home computer in the 80s and an all-timer in the puzzle genre.

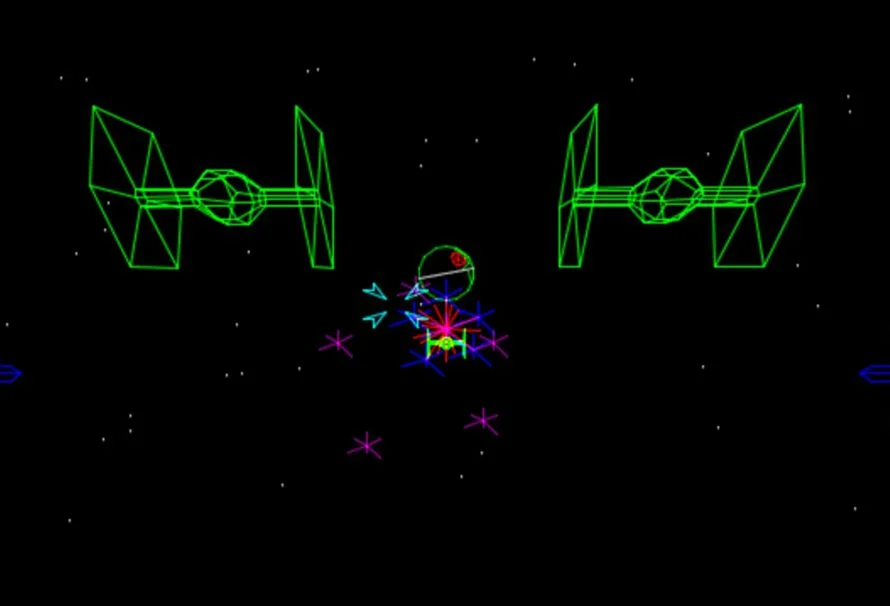

Star Wars

Atari’s Star Wars arcade game was a rail shooter which came in both stand-up and sit-down versions and had players pilot an X-Wing fighter in one of three scenarios: Shooting down TIE fighters, attacking the Death Star, and doing the movie’s final trench run. The game used 3D color vector graphics and digitized voices to provide a wonderfully polished experience and for many it was the best arcade game of 1983. It would be Atari’s top-selling arcade game of 1983, but the numbers it put up weren’t great when you consider the arcade market shrank by nearly 50% in 1983.

Cliff Hanger

Following on the trend of LaserDisc games set by Dragon’s Lair was Cliff Hanger, another QTE game which kept costs lower by recycling footage from Lupin III movies, specifically Castle of Cagliostro and The Mystery of Mamo. Though rather than actually mentioning Lupin, players play the role of “Cliff Hanger,” a dashing spy on a quest to save a beautiful princess and aided by his friends “Jeff” and “Samurai.” As a game, Cliff Hanger is better than Dragon’s Lair, incorporating a second action button and again mostly focusing on quick time events to get through the animated story. The whole thing takes about 15 minutes on a perfect playthrough, but actually making that happen when you have to drop fifty cents per play can be a tall order. One of the more interesting things to note about the game is that it was released prior to any theatrical or home video releases of Lupin III in the US, and so despite not being terribly popular was many Americans’ first introduction to Lupin and the works of Hayao Miyazaki.

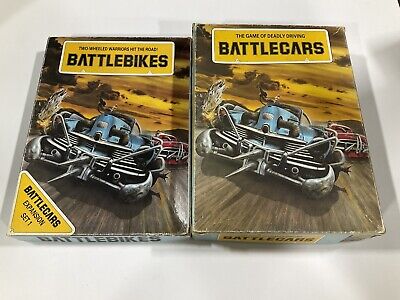

Battlecars

Games Workshop looked to get in on the success of Steve Jackson Games’ Car Wars in 1983 by launching their own Mad Max-inspired game of vehicular warfare. Battlecars wasn’t particularly successful and was replaced five years later by Dark Future, but it did pave the way for that game and it’s an interesting pit stop on the way to Games Workshop figuring out what kind of games they were going to make.

The Birth of Gen III Consoles

If there’s a silver lining to 1983, it’s one of the most important ones in all of gaming history – July 1983 marked the initial release of the Famicom (short for “family computer”) in Japan, the console which would eventually make its way to the United States in 1985 as the Nintendo Entertainment System, kicking off a near ten-year run of market dominance for Nintendo that would completely revitalize and reinvent the video game industry. Alongside the Famicom was Sega’s SG-1000, the company’s first foray into the home gaming hardware business, though that would later be replaced by the Master System in 1985.

Why It Was the Best Year in Gaming

It’s hard to make a case for 1983 as the best year in gaming. It was certainly an important year for gaming – maybe one of the most important, as it set the stage for Atari’s downfall, the decline of arcades, and cleared the way for an entirely new set of players to emerge on the scene two years later. In that respect, 1983 gives us the first of what will be a semi-regular occurring series of “transition years” between console generations, where the stream of great releases slows as developers gear up for the next generation.

That said it’s far from the worst year in gaming – not even close, really. 1983 had some solid games – I’ve played Talisman recently, Scotland Yard and Mario Bros. still hold up, and Lode Runner’s an all timer – but the biggest games of 1983 were mostly games released the prior year. The biggest arcade titles of the year were a pair of LaserDisc games that were more groundbreaking than they are fun to play, an extremely solid Racing game sequel, and a top-down car shooter. It’s not a bad crop, but it’s just not on the level of the prior or following year.

This article is part of a larger series on the best year in gaming. For more years, click this link. Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.