Last year’s stacked lineup of games for the Game Awards had us thinking: What was the best year in gaming? As part of our series on determining gaming’s best year, we’re putting together an article on each year, charting the major releases and developments of the year, and talking about both their impact and what made them great.

The Year: 1991

1991 marks the real beginning of the console wars. While Sega struggled to pull ahead of the PC-Engine in Japan, in the United States and Europe they’d procured a sizeable lead over Nintendo – particularly in Europe, where the Super Nintendo wouldn’t release until nearly two years later. Thanks to Nintendo’s licensing policies (which forbid cross-platform games), Sega’s strategy was always going to depend on their first-party library, which was heavy on arcade ports. The Genesis had a strong library of arcade ports to pull from in its first three years, but still struggled to gain ground against Nintendo in the United States.

In 1990 Sega of America hired a new CEO: Tom Kalinske, former president of Mattel. Under Kalinske, Sega of America opted for new marketing positioning for the Genesis, choosing to target an older, teenage demographic. The Genesis was marketed as the console your cool older brother would play, with lots of sports games and darker, more adult arcade ports. Sega dropped the price of the Genesis prior to the launch of the Super Nintendo and worked on deals with Electronic Arts and other US developers to produce sports games for the Genesis. But the real game change for the Genesis was the arrival of Sega’s first true mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog. The first Sonic the Hedgehog released in mid 1991 and was immediately made the pack-in for the Genesis, even going so far as to offer the game free to players willing to trade in Altered Beast, the console’s prior pack-in.

All of this was paired with an edgy, attention-grabbing marketing campaign which positioned Sega as a cooler, more adult brand and Nintendo as a dopey kids’ toy. Print ads proclaimed that “Genesis Does What Nintendon’t” and Sega made heavy use of the nascent gaming press for their campaigns. The efforts would pay off – Sega’s larger library of games helped it power past Nintendo early in the 16-bit cycle and while the Super Nintendo would outsell the Genesis in 1992, Sega would end the year with a larger install base and a 55% market share.

The Sega CD

Released in December 1991 in Japan, the Sega CD (or Mega-CD outside of the US) released in the US in 1992 and everywhere else in 1993. Although the 16-bit console wars were in full swing, CD technology was gaining traction, replacing tapes. NEC had already released a CD-ROM drive add-on way back in 1988 for the PC-Engine/Turbografx-16, which gave it the ability to play games stored on CDs. By 1991, Nintendo and Sega had both announced their own CD player add-ons for the Mega Drive/Genesis and Super Nintendo/Famicom.

The Sega CD was an interesting beast; as an add-on for the Sega Genesis, it can’t be used as a standalone device but requires its own power supply. The device has its own CPU, additional RAM, and a custom graphics chip capable of sprite scaling and rotation, similar to mode 7 graphics on the Super Nintendo, only with the ability to scale/rotate multiple sprites at the same time. Of course the biggest feature was having CD-ROM discs for storage, which meant up to 650 Megabytes as opposed to 16-32 Megabits, allowing for games with full motion video. This was a blessing and a curse.

The Sega CD launched with a $299 price tag (roughly $422 today), with six launch titles: Heavy Nova, Sol-Feace, Nostalgia 1907, Earnest Evans, Wakusei Woodstock: Funky Horror Band, and Tenka Fubu; Eiyuutachi no Hokou in Japan, with most of those never seeing US release. Instead the US would get its own launch line-up, featuring Prince of Persia, Black Hole Assault, Sewer Shark, INXS: Make My Video, Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch: Make My Video, and a relatively tasteless FMV game called Night Trap. More on that in 1992.

If that launch line-up doesn’t appeal to you well, you’re not alone. Sega of America was famously kept in the dark during the development of the Sega CD, and sent only non-functioning “dummy” units to avoid any chance of leaks. Given how Sega of America had been instrumental in the success of the Genesis, this was a major misstep on the part of Sega of Japan and marked the growing tensions and gulf between the two groups.

CES 1991

While Sega was partnering with JVC to develop its Sega CD add-on, Nintendo was working on its own partnership with Sony to develop a CD-ROM drive add-on for the SNES. In addition to the add-on, Sony would develop its own Super Famicom hybrid console, which was to be called the PlayStation. The system was planned to use Super Disc format for its CDs, a proprietary format owned by Sony. Given Sony already developed the system’s sound chip and was clearly looking to grow past its partnership, as well as the bad terms for them, Nintendo became suspicious and secretly planned to back out of the deal, hoping to avoid making another competitor for themselves in a market that had suddenly become very competitive.

This all came to a head at the 1991 Summer Consumer Electronics show when Sony went on stage to officially announce their partnership with Nintendo to develop the SNES PlayStation system. Then a few hours later, Nintendo went on stage to announce that, actually, Sony wasn’t going to do shit and Nintendo had chosen to instead partner with Phillips on a CD drive add-on.

This was an incredibly shitty move by Nintendo, publicly humiliating Sony on one of the industry’s biggest stages. It was so bad that Sony strongly considered just dropping the project and getting out of the video game business altogether. But lead developer Ken Kutaragi convinced the company to stay in it and develop the PlayStation as its own console. By 1992 they’d completely cut ties with Nintendo and had begun to develop their device with a focus on 3D graphics. We’ll check back in with Sony in 1994 to see how that panned out.

Philips CD-i

As part of Nintendo’s partnership with Philips they agreed to license some titles to the company for their CD-i (Compact Disc Interactive) platform. More a souped-up video player than a true console, the CD-i had a controller peripheral and could nominally play games. Although Philips was primarily selling the device as an entertainment device and not a game console, they’d eventually make an attempt to move into the game market with a handful of Nintendo franchises, publishing Hotel Mario and three Zelda games, all of which are widely known for being absolute dog shit. But in wonderful, hilarious ways. If you haven’t seen videos of Zelda: Wand of Gamelon or Link: The Faces of Evil, it’s worth finding them on YouTube. They’ve practically become rites of passage for YouTubers who play bad games.

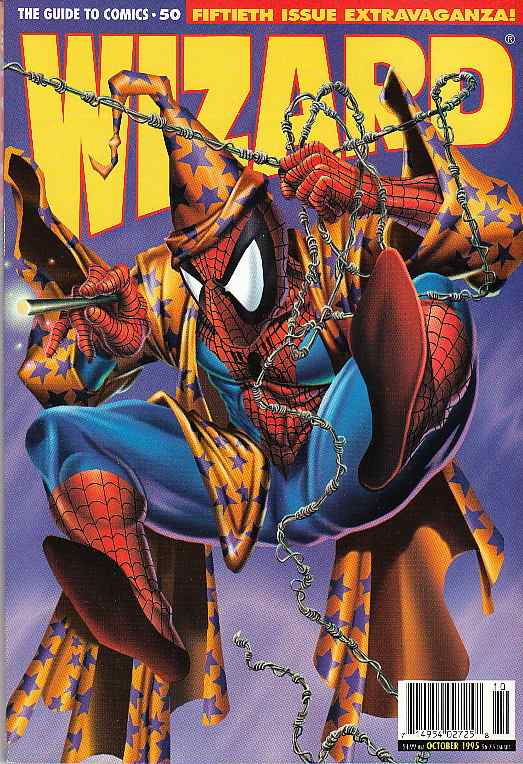

Wizard Magazine

Founded by Gareb Shamus in 1991, Wizard Entertainment started publishing this magazine as a comics price guide in 1991. Marvel had undergone a renaissance in the late 80s as Chris Claremont took over writing duties on most of the company’s mutant-related comics. That interest would explode in 1991 when Claremont partnered with artist and co-writer Jim Lee to launch a new series titled simply X-Men, featuring Lee’s iconic Magneto artwork on its most common cover (the book famously featured multiple covers which could be put together to make a spread). The book broke records and was indicative of the growing collector market for comic books. The frenzy around buying and selling old comics ultimately led to magazines like Wizard, which published regular price guides for back issues of comics, to help collectors properly value older issues. Wizard would go on to start other magazines in the gaming space, run conventions, and cover a large swath of pop culture.

Sonic the Hedgehog

It helps that the original Sonic the Hedgehog is a fantastic game, with large colorful sprites, great gameplay, fast action, and good challenge. The game is an absolute classic and on par with any of the Mario games in terms of its simplicity and sheer fun. The game features a bright, imaginative world, fun action, and fast platforming that encourages replay and speed runs. The only thing keeping the original Sonic off gaming’s Mount Rushmore is the fact that the second and third games in the series are so much better. Sega was also helped tremendously by the fact that Sonic was an incredibly strong mascot – instantly likable and visually distinct, and is still the company’s mascot.

White Wolf Publishing

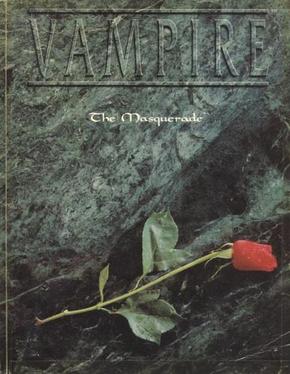

Founded in 1991 as part of a merger between Lion Rampant and White Wolf Magazine, White Wolf Publishing would go on to publish perhaps the second most important series of tabletop RPGs with its World of Darkness. Starting with Vampire: the Masquerade in 1991, White Wolf introduced players to a world like their own, but populated with all manner of supernatural beings and horrors lurking behind the scenes, pulling the strings on our everyday lives. They’d go on to expand the universe with games like Werewolf: the Apocalypse, Mage: the Ascension, and Hunter: the Reckoning.

White Wolf’s World of Darkness games were particularly notable for using a D10 system and emphasizing character roleplay over combat and encounters. There were no random encounter tables, no dungeons; only the need to navigate the complicated politics of vampire society, evade detection by regular humans, and manage a growing web of lies and deceit. White Wolf’s games were much more adult than traditional tabletop RPGs, particularly D&D, and tended to go heavy on horror themes. As a result, they tended to draw in a very different audience. If Dungeons & Dragons is what your dorky younger brother played, then Vampire: the Masquerade was something you’d see goths and theater kids doing.

Vampire: the Masquerade

White Wolf’s first game set the stage for the World of Darkness, introducing players to the shadowy clans of modern vampires who run things from behind the scenes. Vampires were no longer deformed creatures of pure bloodlust (well, ok, some of them still were), but rather cool, sophisticated characters looking to enjoy their eternal life and exert control over humans and each other. It’s hard to overstate the impact Vampire had on vampire lore and stories – many movies, shows, and games owe Vampire: the Masquerade for its conception of Vampires as a series of ancient houses meeting in board rooms to determine the future of their species. Marvel’s Blade in particular does this, and Underworld is so close to the World of Darkness that White Wolf filed suit against Sony Pictures afterward.

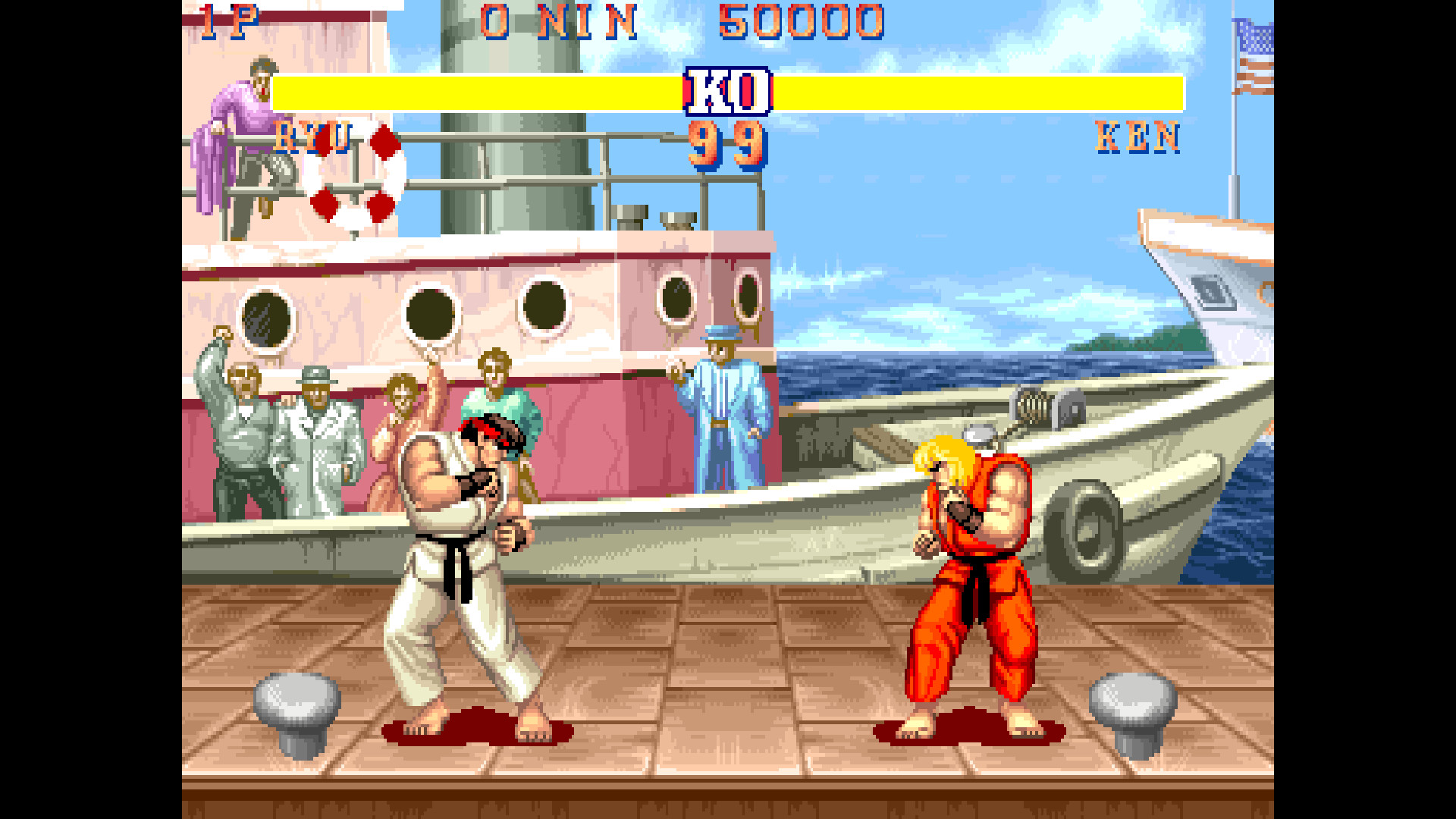

Street Fighter II

Capcom straight-up changed the world in 1992 with its 14th CPS1 game. Street Fighter II: The World Warrior hit arcades in March of that year, featuring an updated roster of eight playable characters, each with different moves and styles. The game emphasizes two player head-to-head combat, and gives players the ability to link and cancel moves into combos and perform special moves using precise button inputs. The original Street Fighter was OK for the time but was largely a bad game. Street Fighter II was an iconic classic that single-handedly defined the fighting game genre and set off a movement which would revitalize American arcades.

Street Fighter II took a little bit of time to pick up steam but American players took to the game quickly and by the end of the year it was the highest-grossing arcade game in the US as it made its way toward generating billions of dollars in profit for Capcom. The only reason it didn’t sell more units is because it was replaced in following years by updates like Champion Edition and Turbo. Street Fighter II was a must-have for arcades in the early 90s, and would be a major driver of the US arcade revival in the early nineties, particularly after the release of its chief rival a year later.

Internet Archive – Play Meter 1992

The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past

Nintendo followed up the release of Super Mario World with the third entry in its Legend of Zelda series November 1991. The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past returned the series to its top-down view and had players explore two sides of Hyrule – the standard world and its dark, twisted mirror in a realm where Gannon’s malice and desire for power had changed everything. A Link to the Past redefined and solidified the Zelda formula, introducing us to the Master Sword and the now-common Zelda formula of “do three dungeons, get sword, then do 6-8 dungeons to collect maidens/sages/parts of the Triforce” that would be replicated across the series until Skyward Sword. Regarded by many as the best game in the series, A Link to the Past gives players an expansive world to explore full of mysteries without ever feeling padded or overstuffed. It’s got lots of nice, little character moments and charm and it still holds up exceptionally well today.

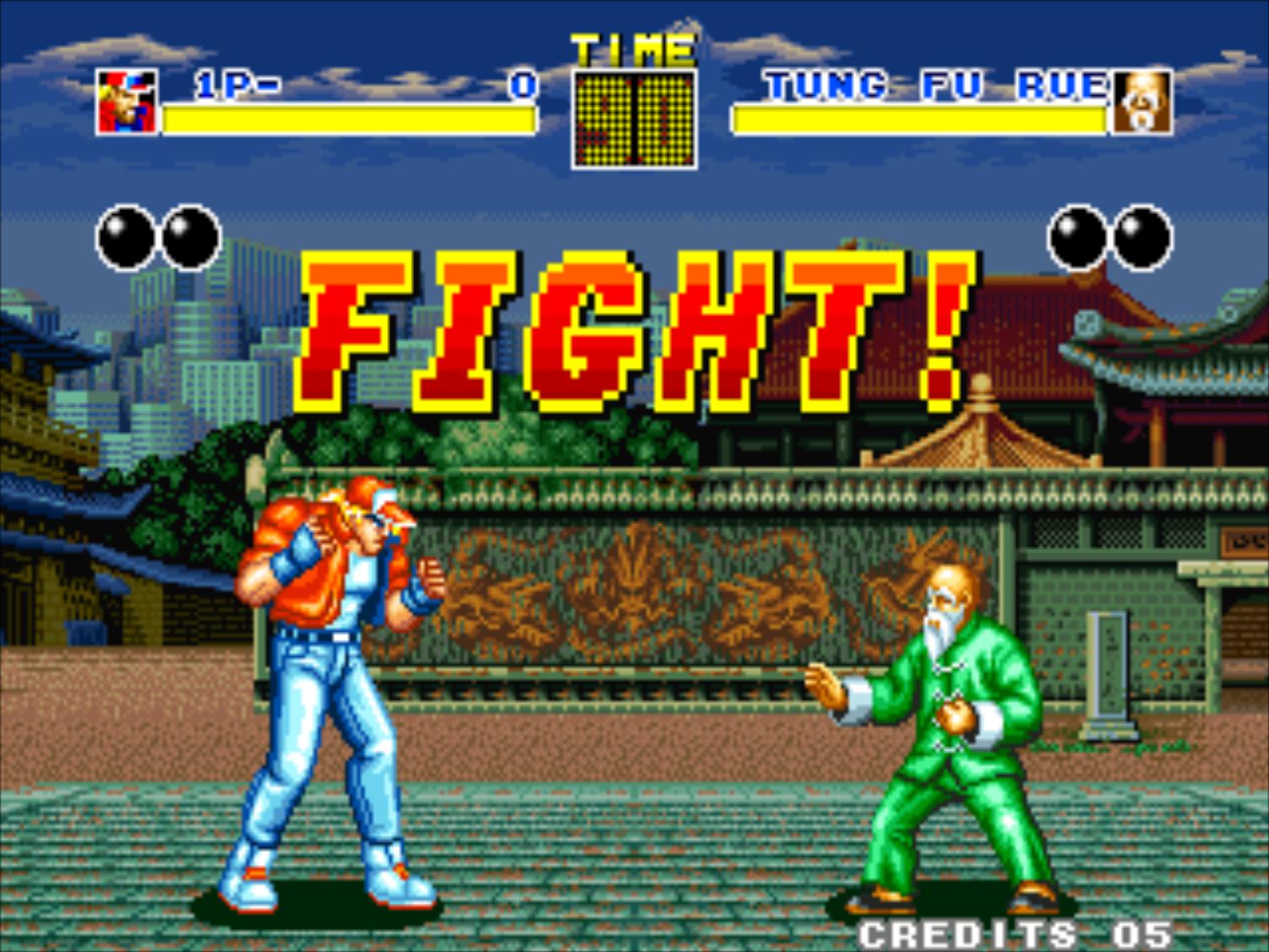

Fatal Fury: King of Fighters

Takashi Nishiyama is in most respects the founder of fighting games. Nishiyama worked on Kung-Fu Master for Irem created the original Street Fighter for Capcom in 1984, but left to work at Capcom before the game was finished. At Capcom he’d ended up directing the original Street Fighter, released in 1987, then left to join SNK. While at SNK, Nishiyama worked on the Neo Geo system and would end up creating some of SNK’s most memorable franchises. First among these was the original Fatal Fury. Released in November, 1991, Fatal Fury was a spiritual successor to the original Street Fighter, and shared a number of traits with Street Fighter II, emphasizing one-on-one fights with punches, kicks, and special moves. Where Fatal Fury brought some extra oomph was giving players two “lanes” to fight on, letting them switch between the foreground and background layers during a fight to avoid attacks and add some three-dimensional movement to the game.

Streets of Rage

When Capcom chose to port its 1989 hit arcade beat ‘em up Final Fight to the Super Nintendo, it both gave the console a strong title and also meant that Sega would need to develop its own game if the company wanted to compete with Nintendo, who had already owned the genre for years with the Double Dragon series on the NES (though Sega had some chops there with Golden Axe). So Sega got to work and in 1991 released Streets of Rage for the Sega Genesis in the US and Japan. Streets of Rage is a side-scrolling beat ‘em up about three former cops who take on a crime syndicate. The game adds a ton of environmental hazards and weapons and was an immediate success for Sega, giving them a real answer to Final Fight and kicking off a franchise which would be wildly successful for the console.

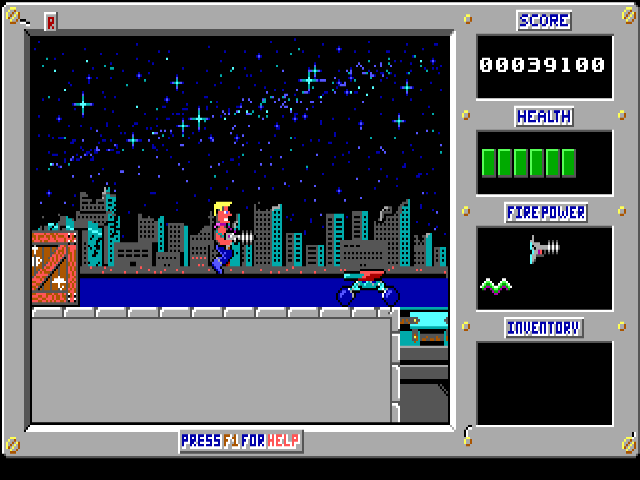

Duke Nukem

Released for Windows and MS-DOS in 1991, the original Duke Nukem was a platforming run-and-gun game that featured scrolling levels – at the time still a difficult task for computers and one that would be solved by John Romero and John Carmack. The game’s first level was distributed as shareware, letting players play the start of the game before buying the rest – a model which would become popular under developer Apogee in those early days, particularly in the following year with Wolfenstein 3D. Duke Nukem was very successful and was essentially the first major platforming game for the PC.

Final Fantasy IV

Squaresoft made the jump to the 16-bit era in 1991 with Final Fantasy IV, a game which had been in development concurrently with its predecessor. Launched in the US as Final Fantasy II (the actual second and third games for the NES were never released in the US), the game went bigger and more cinematic with the game’s story than ever before, giving players a shifting cast of named characters to control rather than letting them build a customizable party. The game’s story saw players travel the planet, go underground, and battle enemies on the moon, all backed by incredible sprites based on the art of Yoshitaka Amano and a fantastic soundtrack from Nobuo Uematsu. The game immediately set the high watermark for 16-bit RPGs.

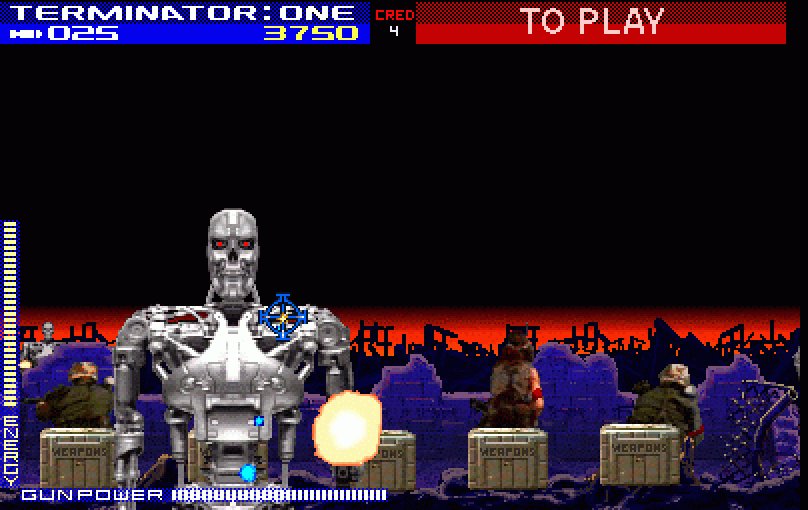

Terminator 2: Judgment Day

Released shortly after the blockbuster movie hit theaters, Terminator 2: Judgment Day was a light gun shooter which featured digitized graphics and had players take on the role of a T-800 fighting for the future (and past) of humanity. The game was developed in tandem with the movie and featured a number of its actors and had some amazing graphics for the time, plus a branching path at the game’s end with multiple endings. There were better arcade games in 1992 but this was the best of the light gun shooters and absolutely captured the magic of the year’s (decade’s?) biggest movie.

Civilization

Sid Meier kicked off the defining franchise of the 4x genre (Explore, Expand, Exploit, Exterminate) with 1991’s Civilization from MicroProse. In this turn-based strategy game, players rule over an entire civilization, guiding them from a small number of farmers to a massive empire, managing their diplomacy, military, and resources along the way. Despite being a sim game, Meier kept Civilization firmly grounded in elements he felt would be fun for the player and the result is one of the most important strategy games ever made. While the game is eclipsed technically by its sequels, the original is still an all-timer and the game paved the way for a number of other strategy games such as Age of Empires, Alpha Centauri, and pretty much every 4x made since.

Shatterhand

By 1991 most developers had moved on from the original Nintendo/Famicom system. Games for it were still releasing apace in the United States, but many of the best titles in that set had been released in Japan a year or two prior. 1991’s Shatterhand stands out from this group as an incredibly well made 2d action platformer with some of the console’s best graphics. It’s as strong a release as the NES saw following the US release of the Super Nintendo.

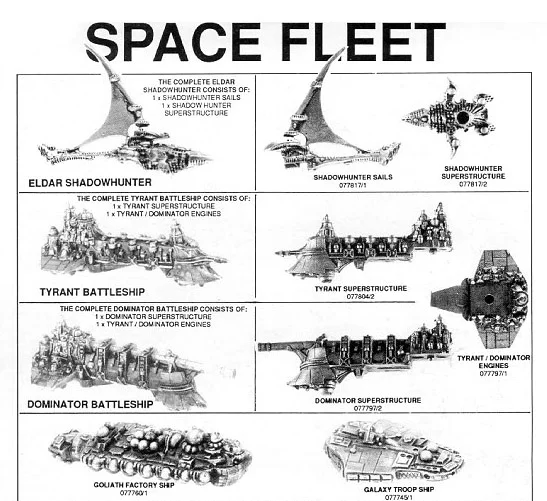

Space Fleet

This 1991 Games Workshop fleet board game was designed by Jervis Johnson and Andy Jones focused on space combat between ships in the void. It’s the standard issue GW standalone game they’d drop a year later but the game is in many ways the blueprint/precursor to Battlefleet Gothic.

Bonk’s Revenge

Although the caveman Bonk gave the PC-Engine/Turbografx-16 a solid mascot two years earlier, Bonk never really caught on in the same way as Sonic or Mario. Which is a shame because 1991’s Bonk’s Revenge is a solid platformer, if not quite on the level of those two games – it’s a little too short and a little too easy – but it’s a game with tons of charm.

Metroid II: Return of Samus

One of the rare Nintendo games to see a US release before a Japanese release, Metroid II: Return of Samus was released in November, 1991 for the Game Boy in the states. The game gave players a major overhaul of the classic Metroid formula, seeing Samus venturing deep into the underground caves of the Metroids’ home planet, SR388 and exterminating every last one of them. The game has great atmosphere and some genuine suspense and it’s easily in the top five games for the original game boy along with Tetris and the Pokemon games.

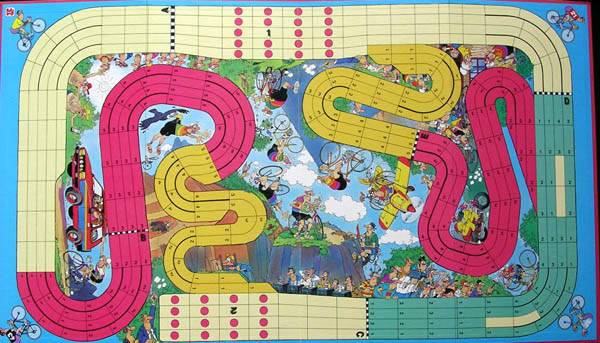

Um Reifenbreite

Raf Cordero: The 1992 Spiel des Jahres winner is a game that has had a couple of titles over the years, Um Reifenbreite is German for “by the width of a tire”. In this game of bicycle road racing players each control a team of 4 cyclists. As is appropriate, the winner is the person whose team scores the most points overall. While you may have the overall race winner who earned the most individual points, you need to make sure you haven’t overplayed your hand of cards on that one racer.

Play combines dice with a hand of one-shot cards and takes place across a series of rounds. While a round ends when all riders have moved, play isn’t necessarily sequential because of the way riders can draft. For normal movement, a player rolls some dice and moves that many spaces. Your hand of energy cards can be played to swap a die for the value of the card. This gives you a bit of control over movement. Instead of normal movement, your rider can draft. This involves simply following along behind when the rider in front of you moves and can lead to chains of riders drafting along.

Drafting adds some interesting decisions and again helps mitigate luck. If your rider is out in front you’ll have no choice but to accept the whims of the dice, but those riders in the peloton have the option of taking advantage of someone else’s good roll. You can opt to say that your rider is “breaking away” when you use an energy card, but that is not always beneficial. Advanced rules (which are highly recommended) add movement tweaks to simulate uphill/downhill and other road conditions, and even introduce an option to have your rider cheat by grabbing a car and hitching along for the ride. A deck of photograph cards make this a risky proposition.

Another early Spiel winner that is now out of print, Um Reifenbreite is going to require you to hit eBay if you want to check it out. Flamme Rouge, a game clearly inspired by Um Reifenbreite, is readily available and an excellent substitute.

Why It Was the Best Year in Gaming

1991 produced a ton of great games, and was an incredibly important year for both 16-bit gaming and tabletop gaming. The first year of the 16-bit console wars opened with some great opening volleys from both Sega and Nintendo, and the release of Street Fighter II in arcades kickstarted a movement which completely revitalized the American arcade scene. We didn’t mention them but other stand-outs from 1991 were Mega Man 4, Super Ghouls ‘n Ghosts, Battletoads, SimCity (SNES), and Super Castlevania IV.

On the tabletop, White Wolf gave us cooler, more mainstream tabletop role-playing games with the introduction of Vampire: the Masquerade and its World of Darkness. White Wolf may never have outsold TSR and Dungeons & Dragons in the 90s but they expanded the market for tabletop RPGs in a way that D&D never could, even as TSR began to struggle, and quickly became the second largest player in the space.

This article is part of a larger series on the best year in gaming. For more years, click this link. Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.