Last year’s stacked lineup of games for the Game Awards had us thinking: What was the best year in gaming? As part of our series on determining gaming’s best year, we’re putting together an article on each year, charting the major releases and developments of the year, and talking about both their impact and what made them great.

The Year: 1981

Even with Ronald Reagan’s presidency only in its first year, 1981 in games foreshadowed the jackpot soon to come to the United States via Reaganomics. 1981 was already a Deadwood gold rush of game sales, innovation, rule-breaking, and rapid discoveries in new frontiers. Only booms, no busts. It was a multiverse of origin stories and multitude of firsts. All corners of gaming – new and old – collided with each other in endless multiball mode, meeting and beating all previous high scores. It was a sensory overload, through-the-Looking Glass year that forever changed the history and trajectory of games and gamers.

Spacefarers – The “Blink and You’ll Miss It” Warhammer 40K Gateway Game

Game Workshops’ sole board game release in 1981 was a minor footnote but a major source of inspiration: a sci-fi skirmish game called Spacefarers. From the box: “designed specifically for the Spacefarers range of figures manufactured by Citadel Miniatures Ltd… rules have been designed for two players to carry out small scale skirmishes with each player in control of a unit of Imperial Marines, Dark Disciples, Star Patrolmen, or independent gangs.” (Sounds familiar.) Six years later we’d see the first edition rulebook of Warhammer 40,000, in September 1987.

The Golden Age of Dungeons & Dragons

In the seventies the Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) role-playing game system was still a niche novelty that successfully spun off from another niche novelty – tactical and historical tabletop wargames. The “D&D recommended if you like” quote from the introduction to Dungeons & Dragons – Book 1 – Men and Magic by Gary Gygax & Dave Arneson (1974) is a manifesto of aggressively non-mainstream interests like vintage pulp fantasy, pulp sci-fi, and grognards. Gygax was just daring the normies to try grokking D&D:

“Those wargamers who lack imagination, those who don’t care for Burroughs’ Martian adventures where John Carter is groping through black pits, who feel no thrill upon reading Howard’s Conan saga, who do not enjoy the de Camp & Pratt fantasies or Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser pitting their swords against evil sorceries will not be likely to find DUNGEONS and DRAGONS to their taste.”

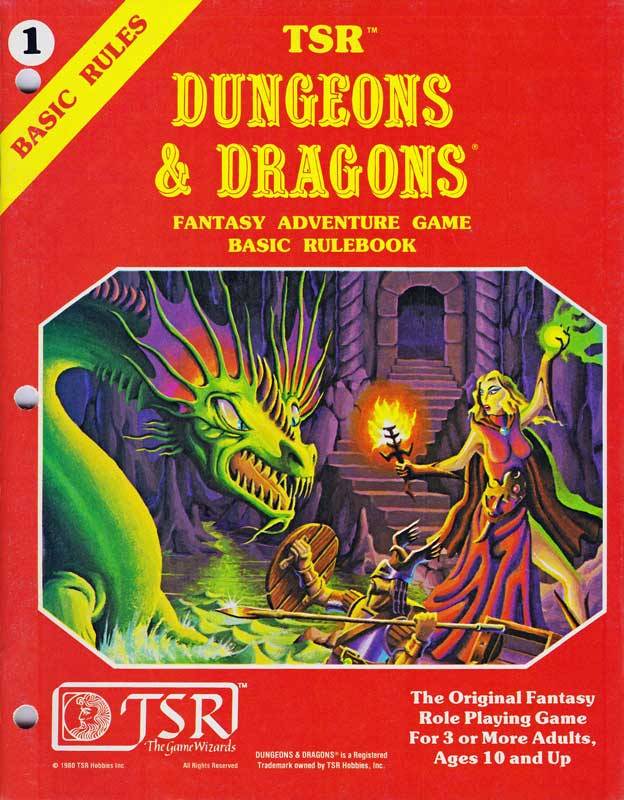

There was nothing in D&D’s DNA that suggested a leveling-up from “those whose imaginations know no bounds” geeking out in the basements and back rooms of hobby stores to greater widespread, gateway appeal. But 1981 changed all that, and 1981 surprisingly became D&D’s Beatlemania moment and “overnight” success.

D&D’s rise began in 1979 when James Dallas Egbert III, a student at Michigan State University, went missing from campus (after leaving a troubling suicide note). He was found alive and safe one month later in New Orleans, but the private investigator hired by the Egbert family glommed hard onto Egbert’s interest in Dungeons & Dragons as a (strawman) link to both Egbert’s month-long disappearance and his overall state of mind. The police and national news outlets – with scant leads and little understanding of what their kids were “into” – printed lurid and sensational “D&D made me do it” headlines – a new riff on the Satanic Panic youth culture wars which (all-press-is-good) thrust this cult role-playing game into mainstream culture. Dungeons & Dragons crashed through 1981 like the Kool-Aid Man, and the aftershocks rippled beyond the RPG bubble into all forms of entertainment at the time.

In September 1981 author Rona Jaffe dashed off a schlocky, bestselling, “ripped from the D&D headlines” novel, Mazes and Monsters. A melodramatic television adaptation starring Tom Hanks fast tracked a year later. Also in September 1981: Steven Spielberg’s new film E.T. the Extraterrestrial began filming. It included an opening scene during which a group of teens play D&D at the kitchen table (with the kid brother and soon-to-be-alien-befriender Elliott begging to join their campaign). This moment in celluloid history became the inciting incident for the Duffer Brothers’ Stranger Things franchise. TSR Hobbies’ D&D was well on its way to becoming the Bahamut of all media.

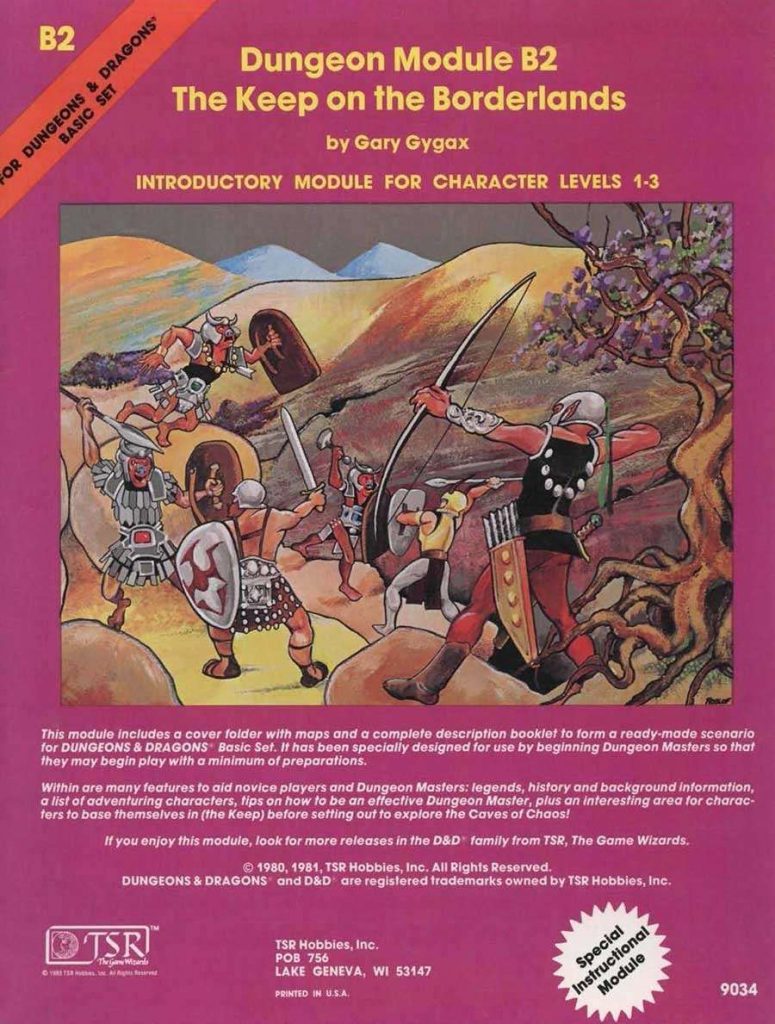

It was in that 1981 TSR Hobbies introduced their fully revised edition of the Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set which featured artwork by Erol Otus, six polyhedral dice, and a marking crayon to ink them. It also included Gary Gygax’s republished (B2 The Keep on the Borderlands) as a gateway adventure – now considered one of the greatest D&D modules of all time. The iconic Red Cover box set sold 750,000 copies in 1981.

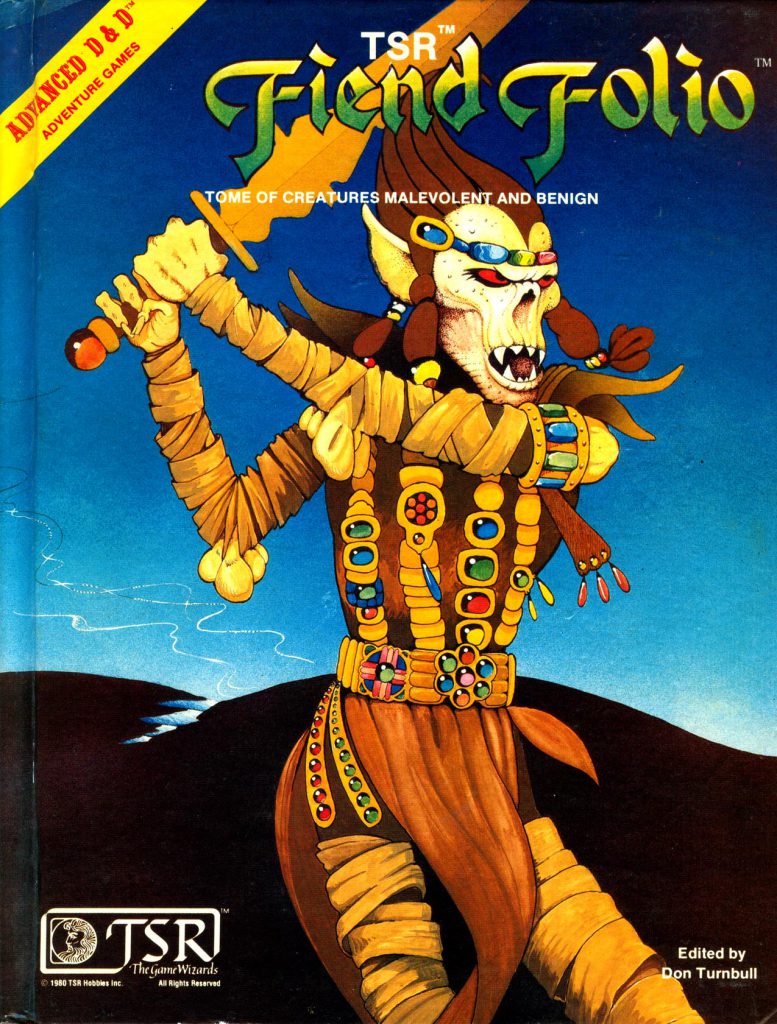

TSR Hobbies also made the canny move of awarding UK company Games Workshop the official license for all things Dungeons & Dragons abroad. Selling directly from UK brick-and-mortars cut TSR’s overhead for overseas shipping and taxes from the States. Games Workshop wasn’t just a distribution hub, either. The followup tome to the original 1977 D&D Monster Manual was retitled from Monster Manual II to Fiend Folio. This was due to it being a compilation of “Fiend Factory” submissions originally published in Games Workshop’s own White Dwarf magazine, whose ur-crowdsourcing: readers dreamt up and mailed in their own original creature ideas, hoping to see them in print. With the Fiend Folio adding more content to a white-hot property, TSR Hobbies made $12 million dollars in sales in 1981, which was more than the production budgets for two different epic fantasy films released in 1981: John Boorman’s Arthurian fantasy Excalibur, and the Greek myth swords-and-sandals extravaganza Clash of the Titans.

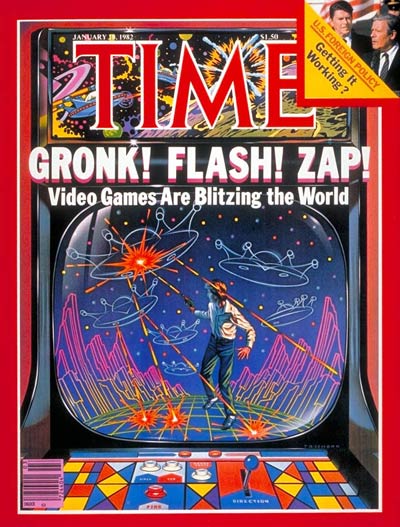

Arcade Games: Number Go Up

In 1981, arcade games made $4.8 billion in the United States. There were 24,000 arcades in the US and 400,000 arcade games in non-arcade venues (restaurants, bars, stores). 1.5 million arcade machines gulped down quarters. The cover story in Time Magazine that shared these figures also reported that video game players spent 75,000 total years playing arcade games in 1981 and that the video game industry earned twice as much money as all Nevada casinos combined. There would be a reckoning coming in 1982, but 1981 was all arcade game upside.

Arcade games in 1981 were like the 80’s pop music scene – lots of chart toppers but also tons of one hit wonders that were footnote “firsties.” Nintendo’s first stateside hit (Donkey Kong, which was released in 1981 but blew up and was covered in the 1982 Best Year Ever.) The first side-scroller to force scroll (Scramble.) First game to offer extra lives for extra quarters, and voice digitized speech (Gorf.) First to have a “Continue Game” feature (SNK’s Fantasy.) But the all-time bangers reigned supreme.

Defender

Williams Electronics first released Defender, a horizontal side-scroller designed by Eugene Jarvis, who pivoted from pinball machines to create one of the most difficult arcade games to master (and engineered the most memorable arcade earworms in video game history). Despite or because of this, Defender sold 55,000 units and accounted for a billion dollars in total revenue, making it Williams’ best-selling game ever.

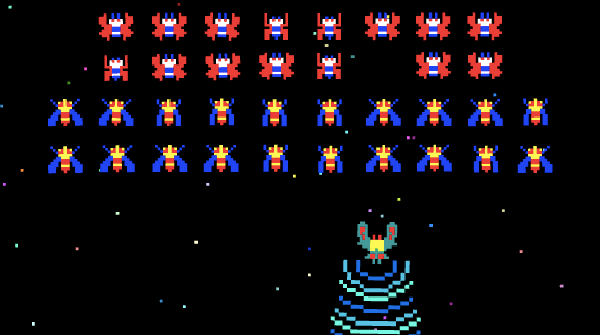

Galaga

Namco’s Galaga (released in the US by Midway) is largely considered the first arcade game sequel. Like Galaxian, it’s another fixed shooter. But Galaga confidently moved away from the Space Invaders template that Galaxian leaned on in every respect. The enemy ranks were now bugs with flapping wings (huge sentient creatures, or insectoid starships?). Some of the baddies now had tractor beams that could steal one of your ships. And if you were skilled enough, you could recapture your stolen ship, and dock it side by side with your current ship, giving you a dual shooter – which made bonus rounds a breeze and provided gamers with the biggest dopamine hit in arcades that year. Galaga far outgrossed the original Galaxian game, spawned two more sequels, and is now considered one of the best games ever made.

Centipede

Insects were HOT in 1981. Atari’s massive arcade hit Centipede was another vertical fixed shooter and bug hunt that offered a unique twist on Space Invaders. In it you were a Bug Blaster zapping segments of a (space) centipede scrolling downwards through a mushroom field. The centipede split into multiple independently moving critters whenever hit, leading to multiple assaults trickling down the screen at you. Mushrooms caused them to reverse direction like pinball bumpers, so an unfortunate funnel of mushrooms could lead to centipedes dive-bombing straight down at you instead of slowly marching row by row. Mushrooms could be destroyed, but any zapped centipede segment created a fresh mushroom

If a centipede reached the bottom of the screen, it would continue to trundle back and forth across the bottom row, but each time invite a new single centipede segment onto the screen from stage left or right to flood the bottom of the screen. And we haven’t even covered Fleas (which drop straight down and leave more mushrooms) or Spiders (which hop around in your Bug Blasters shooting area and kill you upon impact).

This hectic, addictive, adrenalized shooter was co-designed by Dona Bailey (she/her), who at the time was the only woman designer on staff at Atari. Making a game that she herself wanted to see in arcades proved to be a stellar design edict: Centipede was the first arcade game that appealed as much (if not more) to women gamers than men. (This was a 1981 trend as we’ll see.) Centipede crawled (scuttled?) so that later female-friendly games like Ms. Pac-Man (1982) could walk. (Though I argue that Galaga is decidedly high-femme as well).

Frogger

Komani’s Frogger updated the old joke “Why did the chicken cross the road?” with this simple actioner that required one joystick, and no other buttons. You were a frog that had to hop from the bottom of the screen to the top to get back to your lily pad. To do so you had to cross several lanes of traffic and hop onto moving logs and diving turtles to navigate a fast-moving river. You had to avoid a surprising amount of different ways you could die. Hit by a car. Swept off screen on the river by a moving log. Alligators. Mack trucks. Drowning. (Don’t worry about why your frog can’t fall in the water.) The skull and crossbones that appeared when you bit the dust was a nice touch.

This was another arcade game that appealed equally to women and men, which was a novelty in 1981 (and arguably in our current century too).

Qix

Taito released a sleeper hit with Qix, an abstract area majority game that resembled an electronic Etch a Sketch. Qix’s minimalist visuals and simple yet addictive sound effects evoked the imagery of Tron’s lightcycle battles a year before Tron hit theaters.

Home Video Games – Atari VCS (and Everyone Else)

The home video game market made $1 billion in 1981 and the Atari VCS was the biggest earner. One advantage was that they released home versions of their own boffo arcade hits. Atari’s ports of Warlords (a competitive block-breaking paddle game that leveled up Pong) and Missile Command (rollerball + global thermonuclear war two years before the film Wargames) were the Atari’s VCS’s big swings in 1981. (Fun fact: the VCS wasn’t renamed the Atari 2600 until 1982, when their second console was released – the Atari 5200.)

Other gaming consoles that didn’t have Atari’s arcade hit pipeline proved Oscar Wilde’s quote to be true – that imitation was the sincerest form of flattery. Even among the sea of carbon copies there were standouts, such as Intellivision’s Utopia, considered the first electronic city builder and predating SimCity by eight years.

But for the most part it was copycatting. Magnavox’s Odyssey, like everyone else, made their own versions of arcade hits – the self-evident Alien Invaders, a Donkey Kong cosplay called Pick Axe Pete, a Pac-Man riff called K.C. Munchkin (Pac-Man maze clones were legion). Odyssey also published a Reversi clone called Dynasty! to counter Atari’s Othello board game port. Magnavox didn’t restrict its plagiarism to Atari or arcade games. Their video/board game dungeon crawler Quest for the Rings required a game master and included a plastic map overlay that went over the console/keyboard for specific in-game functions. It was clearly their grab at the D&D ring.

Activision: The Beginning of Third Party Devs (and the Beginning of the End for Atari)

More tales of imitation – it wasn’t another home game console (not even their own) that signaled the end of Atari’s golden age. It was the manifestation of third party game developers who skipped the difficulties of making hardware and doubled down on software that piggybacked onto the Atari VCS. The third party dev pioneers were former Atari employees who formed Activision. Led by David Crane (best known for Pitfall!), Activision had a chip on their shoulder and an intimate knowledge of the VCS’s programming quirks and limitations. Their Atari-friendly doppelgangers were smarter, faster, and fun to play. Freeway was a joke made literal: Frogger with a chicken crossing the road. Laser Blast was Missile Command. Activision’s success led to a glut of third party companies churning out cartridges of varying quality and originality, which oversaturated the Atari VCS market. This – plus the arcade crash and leveling up of home computers and games coming within the next 16 months – was the beginning of a bubble that would eventually burst for most existing home game console companies, and Atari in particular.

Computer Games: Pac-Man Fever, Nazi Hunters, and the D&D Effect

Home computer sales gained traction in 1981 and demand for game content followed. Infocom’s previous text adventuring success with Zork spawned more Grues likely to eat you with their Zork II sequel, and a standalone murder mystery called Deadline. Like the Atari VCS, there was a flood of games, and many were forgettable yet shameless homages to existing hits. Every computer had their Pac-Man: there was Munch Man for the Texas Instruments TI-99/4A, Snakman for Commodore 64, and Taxman for the Apple II. (File under “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” – Taxman was so popular that Atarisoft bought and designated the game as the official Apple II Pac-Man port.) The Apple II was one year away from seeing another Pac-man ripoff, Snack Attack, but in the meantime released fungible titles like Beer Run, Bug Attack, and Blister Ball.

Two games did have long-term impact. Ultima I was an RPG good versus evil epic considered the first open-world computer game.

And Castle Wolfenstein was a shoot-em-up that introduced the in-game concepts of stealth and looting, which is now a shooter game default for any AAA title worth its salt. It also proved four decades later that fighting Nazis is an evergreen activity, and not merely in “fantasy” settings for a video game.

Other minor startups drew direct inspiration from D&D’s source texts and were far more memorable. Sir-Tech’s game Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord was one of the first RPG games written for computers, tracking stats and gameplay for an entire party of adventurers. The game included character creation, different classes, equipment, and the gaining of experience and skills while progressing through ten levels of a dungeon. It was a true homage to D&D – and by most accounts the very first dungeon crawler.

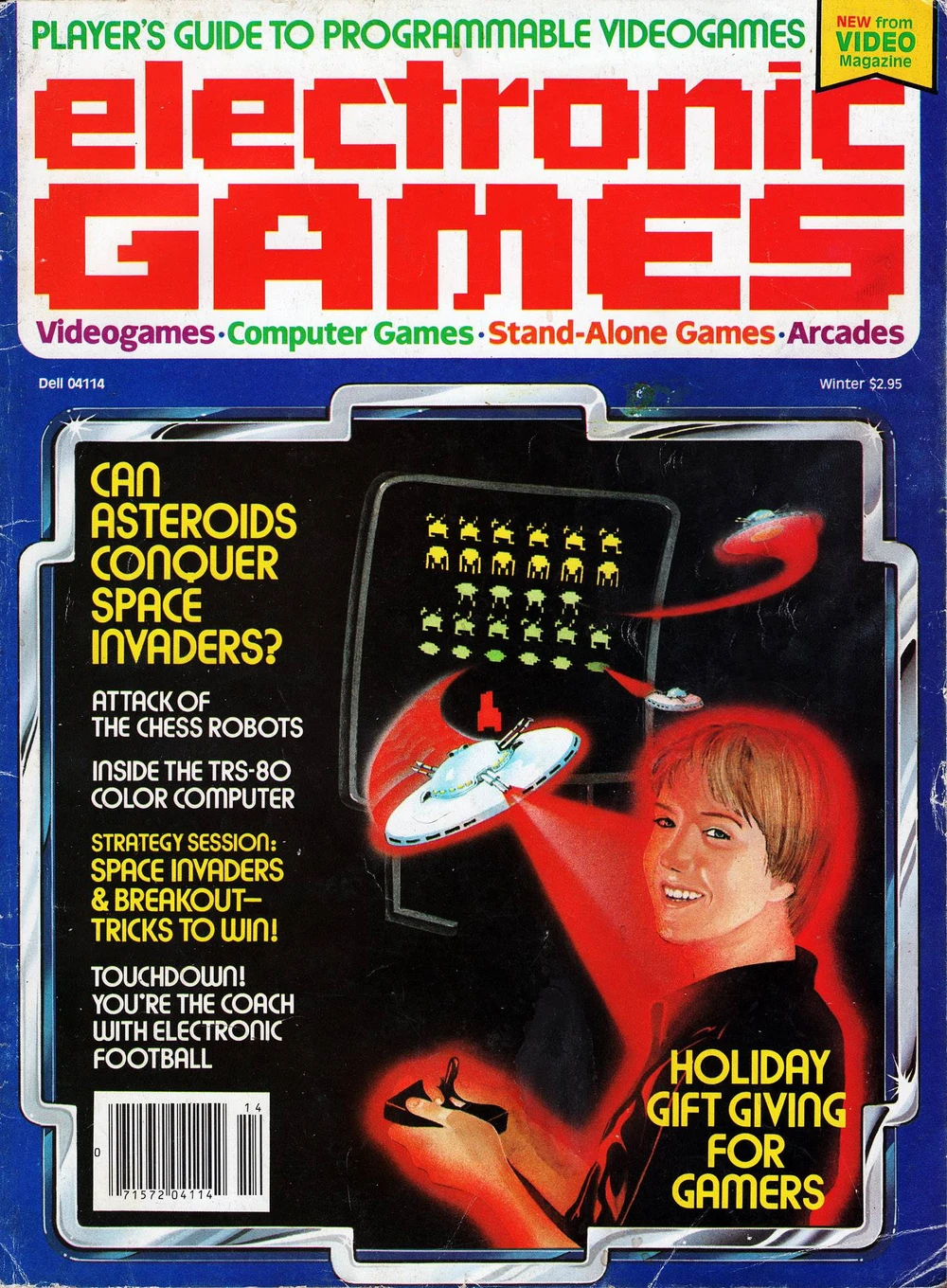

The Birth of Video Games Journalism

Video games may have made the front cover of Time Magazine in January 1982, but it was in 1981 that Electronic Games published its first monthly – making it the big bang of video game journalism. As the first magazine dedicated to video games coverage, EG also created the Arcade Awards to fete their games of the year. Atari cast such a long shadow that the “Arkies” had a “Best Pong Variant’ category for years.

Other gaming periodicals spun up, though none lasted close to Electronic Games’s dominance. EG’s last issue was published in January 1997 – sixteen years after the launch, and seventeen years before the training-wheels extremist movement Gamergate cited “ethics in games journalism” as their justification for a widespread online harassment campaign targeting women, POC, and the LGBTQ+ gamer communities that’s still Chapter One, Page One of the Online Troll Playbook.

Open Source – Share and Share Alike

An Electronic Games magazine contemporary was Analog Computing – notable for including free machine language video games and its source code with each issue, a carryover from the 1970’s with hit games including Hunt the Wumpus and Oregon Trail still “in print.” Two 1981 releases of note: DONKEY.BAS, which was co-written by Bill Gates and originally shipped with IBM PC computers as freeware; and Chuck Benton’s Softporn Adventure, an NSFW “humorous and erotic” text adventure that was the basis for On-Line Systems’ (aka Sierra’s) Leisure Suit Larry franchise.

Call of Cthulhu – RPGs Get Scary

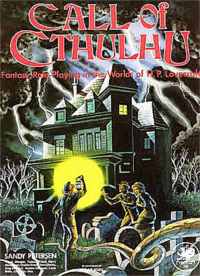

The fantasy RPG Runequest was Chaosium’s first hit in the late 70’s. In 1981 game designer Sandy Peterson pitched to Chaosium a Runequest supplement set in horror author H.P. Lovecraft’s Dreamlands (a setting for several of his stories). Peterson was soon hired to reboot Chaosium’s unpublished horror RPG, Dark Worlds, which he recast and reset in H.P. Lovecraft’s literary universe as Call of Cthulhu.

CoC shares a d100 skills-based system similar to Runequest, and while it was considered a “fantasy” RPG at the time, it broke from the thematic similarities found in Runequest, D&D, and other fantasy systems. Players could still level up and go on adventures. But CoC was set in a more realistic and “modern” era – Lovecraft’s 1920’s. Instead of hack-and-slash dungeon crawling most adventures were investigations, where players did not fight but researched strange events and unexplained phenomena, peeling back layers of a mystery. Caves were swapped out for haunted houses, and monsters were often so powerful and deadly that character deaths (due to violence or madness) were common – even celebrated – during campaigns.

The stylized “realism” and shift of emphasis to conjure the dread and gloom of Lovecraft’s horrific imagination was revolutionary role-playing, and Call of Cthulhu discovered horror and grimdark fantasy as a new dimension ripe for RPG exploration.

The Coronation of Board Game Designer Sid Sackson

The Spiel des Jahres Award winner in 1981 was Sid Sackson for Focus, a game on the “Recommended” short list in 1980. He was competing against himself in 1981 with Can’t Stop, which reappeared on the Recommended list in 1982 as well. And all this after his game Acquire was SdJ short-listed in 1979.

Notably, Acquire and Focus were published in 1963. Sid Sackson’s prominence and the award for Focus (also known as Domination) could be seen as the equivalent of an honorary Academy Award. Sackson was a pioneer in abstract board game design with simple rules, deeper strategies, and sticky, gateway appeal. His games showcased traits that have been found in every Spiel des Jahres entry and winner – sixteen years before the award was created in 1979.

Trivial Pursuit – The Citizen Kane of Trivia Games

The colored plastic pie wedges. The old-timey font and spoked-wheel board. The thick game box that was as heavy as a doorstop. Misreading “genus” as “genius.” If you still associate “Entertainment” with hot pink, then you might be Trivial Pursuit-pilled. The game was first published in Canada in 1981 by Horn & Abbott with a print run of just over 1000 games and was a net loss for the designers. Five years later it would make $600 million dollars in sales and build a massive bandwagon of trivia imitators that even wargame publisher Avalon Hill would shamelessly try to hop onto with a blue box of their own.

What makes Trivial Pursuit the definitive trivia game – then and now – is the breadth and depth of its presentation. The Genus Edition blue box contained 1000 cards of 6000 questions in six different categories. Questions were well-researched and well written. Trivial Pursuit did not feel trivial to play – it seemed to encompass the entirety of all trivia that ever existed within its box. Playing the game one felt erudite, and smart, and even a bit fancy. Trivial Pursuit was as confident as a contestant answering the $100 dollar question in Who Wants to Be a Millionaire and forever changed the landscape. And because trivia was ostensibly open source software, it led to the rapid and unending proliferation of trivia from all directions and across all imaginable formats – board games, party games, computer and video games, game shows, and pubs all over the world.

Axis and Allies – Wargaming Goes Mainstream

Axis and Allies, designed by Larry Harris Jr., was first published as an “indie” by Nova Game Designs. Like Trivial Pursuit, 1981 wasn’t the year that A&A game hit it big but it was the year the game was born.

The 1981 version of A&A was a typical wargame template familiar to core gamers: tacky, busy box art and a creased-paper world map, cardboard chits, a stack of Monopoly money, and an impenetrable Dewey decimal rules set that reads like an edge-caser’s passive aggressive technical manual (”12.3118: “Air units may not move through or into the charts or tables.”) Three years later Milton Bradley bought the rights so it could launch their own Gamemaster series, softened the game’s gatekeeper edges, and gave A&A a glow-up that introduced tactical historical wargaming to the masses in department stores and toy stores instead of boutique (and dusty) hobby stores. It was the first meaty wargame that punched through – a gateway game for those who wanted something more than Risk, and didn’t know (or care) who or what a grognard was.

Dark Tower – Zeitgeist As Board Game

Milton Bradley also published Dark Tower, which in retrospect has to be the frontrunner for “Peak 1981.” It was a fantasy-themed game inspired by both Lord of the Rings (the obsidian tower) and Dungeons & Dragons. It rode the coattails of D&D’s own electronic “labyrinth” board game released in 1980. DT might even have stolen its name from Stephen King’s own Dark Tower fantasy series, which was being released as short stories in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction at the time. Dark Tower was an electronic “computer” game with a microprocessor inside its tower set piece (two D-batteries: not included). And it featured a high-profile and peculiar commercial starring film director and alleged Dark Tower enthusiast Orson Welles.

As a board game, Dark Tower didn’t actually have much under the hood aside from the novelty electronics of the plastic tower. It spritzed light RPG vibes over rote pick-up-and-deliver mechanics, with the beep-boop tower substituting for manual dice rolls to randomize limited outcomes. You were an unnamed Warrior and the NPC’s and locations had no personality, not even names: Brigands, Dragon, Wizard, Tomb, Bazaar. There was no character creation, skill trees, or world building. There wasn’t much game to Milton Bradley’s Dark Tower – but in 1981 there didn’t have to be. Any sense of immersion was 100% player projection and not actually based on lore provided by the game, but by the age you were when the Dark Tower first enchanted you.

Dark Tower was Pew Pew Everythingcore; an object that sought to capitalize on the magic and buzz of 1981: fantasy and sci-fi, Dungeons & Dragons, RPG’s, arcade games, computer and home console games. At a retail price of $65 dollars – $230 in 2024 dollars when adjusted for inflation – Milton Bradley’s Dark Tower bet big that parents would continue spending money on their children after the birth of the blockbuster box office toy craze in 1978 invented by Kenner’s Star Wars action figures.

And it’s no coincidence that Dark Tower captured the hearts and minds (and wallets) of teenage boys everywhere who saw the original Star Wars in movie theaters. Dark Tower, like Star Wars, ushered in the toyification and commercialization of the 1980’s, and formed an entire gamer generation’s love of shiny things, nostalgia, and in some cases, a toxic nostalgia.

Why 1981 Was the Best Year in Gaming

I don’t know if 1981 is the Best Year Ever. Does it matter? What 1981 has going for it is a sheer diversity of excellence in board games, TTRPG, and subgenres of video games (home console, arcade, computer). Add the launch of Electronic Games magazine, when video game discourse was born and with the tropes of gaming discourse (and internet slap fights) we still adhere to today, and 1981 may be in the conversation.

Because everything was still new in 1981, breakthroughs, fads, and revolutionary phenomena happened daily. Growth was sharp across all fronts, riding impossibly huge waves of tech innovation that made personal entertainment options abundant and affordable through computer home consoles, computers, arcade games, and electronics. The heretofore underground or fringe hobby interests of imaginative designers and dedicated players saw mainstream daylight.

Not so coincidentally the Hollywood film industry cratered due to years of a slow economy. This was exacerbated by the seismic arrival of affordable home video cassette recorders and players. 1981 was only a year removed from the Heaven’s Gate debacle, a colossal film flop which bankrupted movie studio United Artists. There was a vacuum in the entertainment space, and 1981 was the year that inventors and companies rushed to fill the gap, carving out a whole new market: home entertainment. Coupled to the growing US economy and families having more disposable income to spend at home and for their kids, 1981 gaming was a tide that raised all ships and forever changed media and culture. And also a bellwether and a mirror to Reaganomic 80’s success, and the greed and excess that soon followed.

Games are more sophisticated and polished today but even the biggest hits claim inspiration from an image, microchip, or moment in 1981. Ironically or not people still Tumblr down 1981 rabbit holes to collect ephemera in the form of Ebay grail quests, Wiki entries, vintage ads, and MAME gameplay. 1981 titles have stood the test of time and have received countless revisits, remakes, and reboots. And even Restoration (Games) – in the case of Return to Dark Tower.

More than most years of this series, 1981 was a watershed, formative moment for those old enough to have directly experienced it as a gamer. To one of a certain age, playing Dungeons & Dragons and Dark Tower at home, Donkey Kong and Centipede in the arcade, watching Excalibur or Clash of the Titans in the theater, and reading Stephen King’s Cujo or Carl Sagan’s Cosmos in 1981 hits different. How can it not? Those formative moments at the table or on the page or screen or in the theater never leave you, and their origin stories become your origin story as a gamer-4-lyfe.

Maybe any given year and The Things We Like automatically imprint upon us this way from K-12 (and beyond). Maybe we all feel this magic and eternal flame of nostalgia for a game, and for Our Own Best Year Ever. But 1981 was a cosmic pivot in the game universe. 1981 was the year that nerd, geek, and gamer culture became capital-S Spectacle and went Hollywood. The ways we play, design, think about, talk (and argue) about games today were born in 1981 – the gateway year for a generation and the Tree of Life from which every gamer can trace back to their own gaming roots, nearly one half-century later.

This article is part of a larger series on the best year in gaming. For more years, click this link. Have any questions or feedback? Drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.