Zachary Cox, aka JellyMuppet, is part of the team behind SoulMuppet Publishing, best known for Best Left Buried and Orbital Blues. They’re also a Goonhammer patron and recently a participant in Turn Order’s Vampire: the Requiem game… which led them to me. Despite our time zone difference, Zach was nice enough to call me up for a chat about just about everything including game design, current SoulMuppet projects, capitalism and vampires.

While some of the games we talked about were fully written by Zach, it’s important to note that the original concept from Orbital Blues came from co-author Sam Sleney. Joshua Clark illustrated the original game and is a co-author for the upcoming expansion, Orbital Blues: Afterburn.

The Kickstarter campaign for Afterburn is entering its final hours and pushing for remaining stretch goals at the time of this article’s publishing. Inevitable, another game we talked about, has recently been released in PDF format. You’ll find Zach on the website formerly known as Twitter at @JellyMuppet.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Talk to me about the process for creating a game. Do you start with a world concept? Do you start with a story concept? Is it different every time?

What happened is I wanted to make a dungeon crawler that kind of focused on horror as something we would try to add to it. And in horror movies, not all the characters die until the end sometimes, right? So, it was about taking the idea and then removing some of the finality from a game, whereas in some of the latest I’ve been working on it’s more been about like, trying to build an engine that’s designed to tell a particular story or exists within a particular world or and or make a particular genre.

Genre is something I really focus on personally as a game designer, and genre emulation is a big focus in the field of games that sort of my work belongs to, which you would loosely describe as “indie story games.” Specifically, stuff that has grown out of things like Blades in the Dark, things like Powered by the Apocalypse and stuff like that in that blooming space. And as a result, the question there is normally like, “what kind of story are you trying to tell or what kind of genre are you trying to emulate?”

You can start from any place and any designer that tells you they do things in only one way has either not made enough games, or they’ve made too many games. It always appears in a different way.

It’s particularly interesting in the game I’ve kind of started writing at the moment, which is this vampire game called Paint the Town Red, where I decided about a year and a half ago that I wanted to make a game about vampires. I’ve been working on it since June 2022, on and off, working out how I want the game to feel, what I want play to be like, what kind of stories I’m trying to tell. I’ve written a lot of words for it in terms of adventures and pitches and mechanical drafts, but it hasn’t been played and there aren’t any rules for it yet.

Sometimes, things just sit and get ideated on for a really long time. But in short, it happens in lots of different ways depending on the need I have as a designer and also a product project manager as well as someone making these games as part of a small business. Because sometimes it’s, “I’ve had this new idea for how a dungeon crawler could work. I’m gonna write it.” Sometimes it’s, “I want to make a game that feels like ‘Cowboy Bebop.’” And sometimes it’s, “I want to write a game about vampires.” It can vary completely in terms of the approach.

What games have inspired the way you design? You mentioned Blades in the Dark and Powered by the Apocalypse. What other kinds of games have you played that kind of made you think, “Oh, I want to make something that works like this?”

The path that I kind of took through playing games… I started playing D&D 5th edition, and then kind of fell through an old school Renaissance pipeline towards games trying to replicate or innovate on the way that games used to be played back in the day. So they’re focused on high mortality, player skill and kind of simulating a dungeon crawl. I kind of started there and then moved into the story game stuff almost accidentally through the kind of stuff I was playing.

I’d say the three biggest influences on my personal games design are a game called Maze Rats, which is done by a guy called Ben Milton, who runs the Questing Beast YouTube channel. For me, that is the quickest “die with your boots on, everything I need to run a game” system where I can just pick up a dungeon on a pamphlet adventure and then just run it and never need anything else. The first game I wrote, Best Left Buried, was almost a hack of Maze Rats – a big hack that added a lot to it, but it really started in that direction.

Blades in the Dark for me was the big second influence and I think is the game I’ve run the most of all of the games I’ve played, including the ones I’ve written as well. Blades is a sort of crime simulator game written by John Harper and published by Evil Hat that is a sort of heist game where you’re trying to play an organized rise in power of this gang in a city filled with ghosts and darkness and demons. It’s very interesting mechanically in that it gives a bunch of levers and there’s a character sheet for the gang. It’s a heist game with no planning, because you’re encouraged to plan everything in flashback scenes. Its handling of the macro economy is really good.

I’d say the third game that has influenced my writing style the most is a really underappreciated game I’ve never managed to play called The Sword, The Crown and the Unspeakable Power, which is a Powered by the Apocalypse game made for playing a Game of Thrones style dark political fantasy game of machinations around the court of a ruler. And the main reason I think about that isn’t so much the structure but every playbook, every ability and every rule feels very genre creating and kind of makes a big structure for the game to appear in. You can read a character sheet and be like, “Oh, I know what this guy is going to do. I can’t wait to play this kind of character.” That’s kind of inspired the, the weight and size I hope to appear from the simple rules that I write when I’m trying to make a game.

I think that the stats that you choose for a game are so relevant in game design. Thinking specifically about Orbital Blues, the stats are Muscle, Grit and Savvy. Can you talk to me about why you chose those three for that game?

The first thing I’d say is that I definitely didn’t choose those stats. Orbital Blues was co-written by myself, and another great creator called Sam Sleney, who’s the main writer on it and I need to make sure he’s referenced anytime I talk about the design of the game because he came up with the draft of it.

I can still give an answer. So, I think choosing stats is a really important part of the game because it communicates the language by which you want to describe the character, right? In Orbital Blues, when me and Sam were coming up with the stats – I might be speaking somewhat to Sam’s process here. Savvy was the first one of the stats that existed, which is how smart and how cool you are. That was kind of used for interacting with people and spaceships and some bits of combat.

Then Muscle was the idea that there might be something else that your character does that is more to do with the body than the mind physically. So like the idea of having a character who was huge or at least powerful had a certain reminiscence there. And Grit is the stat that I think people “get” the least from the game because Orbital Blues is about being a cowboy who’s incredibly depressed, a space cowboy, and going through and dealing with these like meta currencies of tracking your depression. Your experience points in this game are earned by how sad you roleplay your cowboy as instead of when you like, kill monsters or punch bad guys or complete quests or get money. It’s sad for XP. And for me, Grit is something that was the most important role for the game because like, if you didn’t have any grit, your cowboy would just give up. That is like the three ways you could deal with the outlaw galaxy. You can be strong, you can be smart, or you can just put up with shit. And that final one was quite elusive to me.

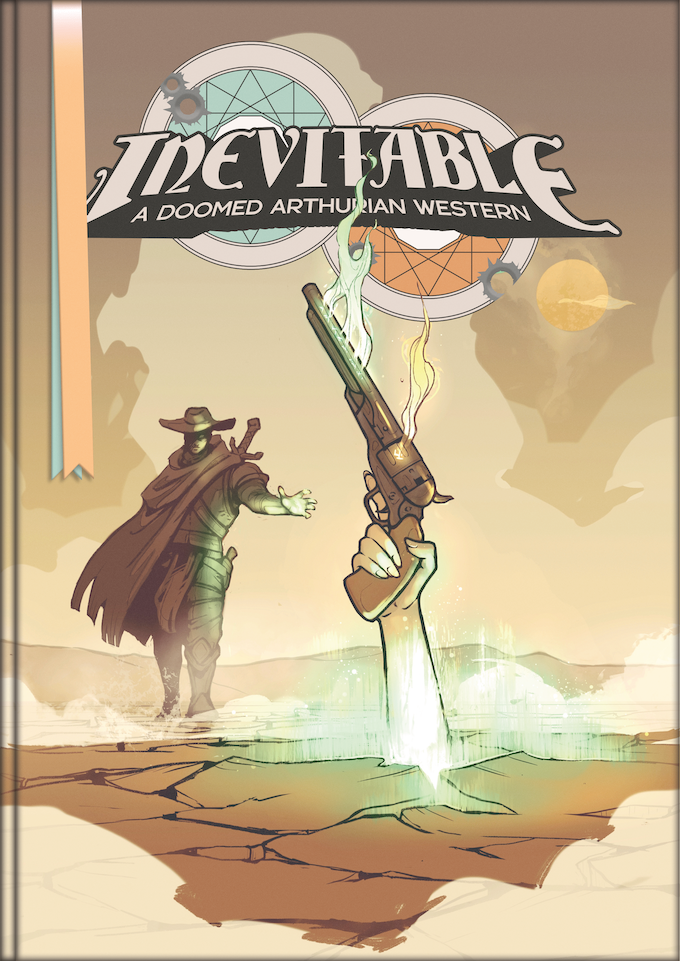

I love the idea of thinking about stats in games as being like the way that we describe characters. When I was writing my most recent full game, Inevitable, I spent a really long time thinking about what stats there should be in this world; Inevitable being a game about Arthurian cowboys trying to stop the apocalypse. And what we decided to move on there was away from the idea of stats and instead to allowing players, when they make their characters, to think about the ways that the people telling legends about the end of the world would talk about their characters. You don’t have a stat that’s got a number on it. You have a reputation. In that space, you get to define what’s important to your character and how they solve problems because a character who is dashing, skilled and graceful is going to solve things very differently to hardy, stubborn, grumpy, right? But those are kind of like the mythic characteristics by which you describe a character.

I think one of the things that defines the type of games I like is that they always have a really small number of stats. The games I make tend to have three, except Gangs of Titan City, which has a solid six, but we can ignore that. There’s usually three stats whereas like, we’re playing Vampire the Requiem at the moment, right, Luke? There’s… how many numbers do you think there are on that sheet?

Just… more than more than anyone can think about.

There’s what like, nine core stats for meta currencies and then like, eight skills for each category of three. You might be dealing with up to like 30 numbers on a character sheet. Whereas for the games I’ve written, there’s never been more than six numbers on a character sheet. That means that those numbers matter more when there’s less of them. Which is one of the things about game design that’s really fascinating to me, is that the less levers you have to pull, the more that each one of them does in the engine.

The thing there is that when you’ve got six numbers, you’re always gonna be able to remember, “I know my cowboy has two savvy, one grit, zero muscle,” whereas despite the fact that I’ve been doing nothing apart from Vampire: The Requiem for the past three weeks, I’d have to really think about what Morgan’s strength skill was. It’s because there are more numbers, so they start to blend together and into the background. (Morgan Shawbrook is Zach’s character in our VtR game. More on that later.)

So, you like not having to go back to your character sheet a whole lot. You kind of want to just know?

Yeah, because for me, role playing games are about telling stories and feeling emotions and having cool things happen. When you have to interact with the mechanics of the game, if the mechanics aren’t telling that story and evoking that emotion, the game has gotten in the way of the play. They should be amplifying things that happen. If I have to stop feeling something to go to the rulebook, and check what the rule does, or read the character sheet or check the wording of an ability I have, that has taken me out of the moment and brought me into a different space.

It’s the same with WarGames as well, weirdly, like the best war games for me are ones that you can play without thinking about that because you’ve memorized how it works. Then you can focus on rolling dice, being with your friends laughing, telling stories. When we have to call the tournament director over to get a ruling over how this armor save interacts with this ability here, something’s gone wrong from the game design perspective, because it’s not clear to the people playing what is happening. That’s why I think the game should always be as simple as they could possibly be made to be. But simple doesn’t mean they can’t be cutting, right? That’s the approach I like to take to making rules exist.

I have to ask you about Inevitable. Where did you get the idea for Arthurian cowboys stopping the end of the world?

I wrote a novel in 2017 after finishing university that was basically “Dark Tower” fanfiction. It was called “The Last Errant” and it was about a white knight who had survived the destruction of his civilization and was wandering around the world trying to get himself killed because he was ashamed that he had not managed to die. He found a boy who managed to teach him how to love again and become a fuller person. It was very Cormac McCarthy and it kind of felt like a mixture between “The Road” and “Blood Meridian,” but kind of set in this world with demons and wizards and other sort of horrible things.

I’ve been trying to write the RPG for that game for six years. It’s been incredibly difficult because one of the gimmicks of the novel and the setting is that prophecy in this world is absolute. There’s no way that you can escape from the future once it’s been told. That’s really difficult to write a long form RPG about, because player agency is something really important in a game. I struggled against that while trying to write this game for a really long time.

What I settled on was taking away the prophecy that was normally about how the character is going to die or what they were going to do when they died and making it instead about a civilization. Your characters live in Myth, which is your sort of Arthurian Camelot in the white desert of the end of the world. The wizards have spoken with one voice, and they’ve said that Myth will be destroyed. Your characters are heroes and legends within this society who have decided that prophecy will not be so and are attempting to stop the end of the world. The tragedy of that story is that they’re going to fail.

It’s a play to lose RPG where that kind of happens, the destruction of this civilization. You’re deciding what you do about it, that being sort of a quite potent metaphor for some of the stuff that’s potentially going on in the world around now. Feeling a sense of impossibility and a lack of agency for your own actions, facing what we now face as a civilization which is all kinds of horrible stuff, right?

I didn’t realize it was Arthurian until much, much later because it was a fantasy Western for a very long time. I made this cast of characters and did not realize that what I’d fashioned was like my own equivalent of the Knights of the Round Table that your characters were then set to join in. They were in service of a young King who doesn’t know what to do in the face of all this destruction. Only then did I realize, “Oh, wait a second. A bunch of these characters that I’ve written really neatly line up with these archetypes in Arthurian mythos.”

From there I basically went, “Oh, there’s three Merlins in this book, what am I going to do about that?” And sort of smashed it all together and finished it up and then decided to put the Lady of the Lake but her hand holding a 1957 Navy Colt revolver glowing with runic magic as if it was Excalibur rising from the lake. That imagery was then so powerful that it was like, I’ve accidentally written an Arthurian Western here while really intending to write a fantasy story. That Arthurian stuff is present in “Dark Tower” in a really meaningful way, like the main character Roland is carrying guns made from Excalibur and he is the descendant of a guy called Arthur Eld.

When you write something referential to something else and you love it for so long and so deeply as I did, and thought about it so deeply, things can kind of morph into a different shape and then only at the end, you realize what it is you’ve actually done.

I just really want to try that game, so I was excited to hear about it.

Mate, it’s fucking sick, it’s really good.

It sounds so cool.

I’m just so proud of it. It’s the first thing I’ve written by myself in a while because Orbital Blues has been with other people, and I’ve been focusing on project management. It seems really good to make something that is uniquely and completely “me,” which hasn’t been for a while.

I’m excited to get to play it eventually. Oh yeah, I should ask: Afterburn is the thing that’s coming up. Tell me about it.

Sam, Josh and I created Orbital Blues two and a half years ago and in crowdfunding we agreed to a really exciting run of short adventures that we did after it and we’ve kind of been working on in the proceeding time, but we always knew there was gonna be a follow up. There was going to be a sort of Orbital Blues… not a sequel, and it’s not a second edition. But it’s the next big thing that we want people to know about. Orbital Blues itself is our game about sad Space Cowboys, it’s this music infused retro future Dustbowl Americana corporate dominance space. It’s a game about being self-employed, living on a spaceship as a sort of itinerant gig economy person, but with this group of people you love very dearly, and you share that space with. It’s borrowing from stuff like “Cowboy Bebop,” “Firefly,” “Guardians of the Galaxy” and “The Mandalorian,” kind of scrappy crews of people who are on a spaceship and care about each other a lot.

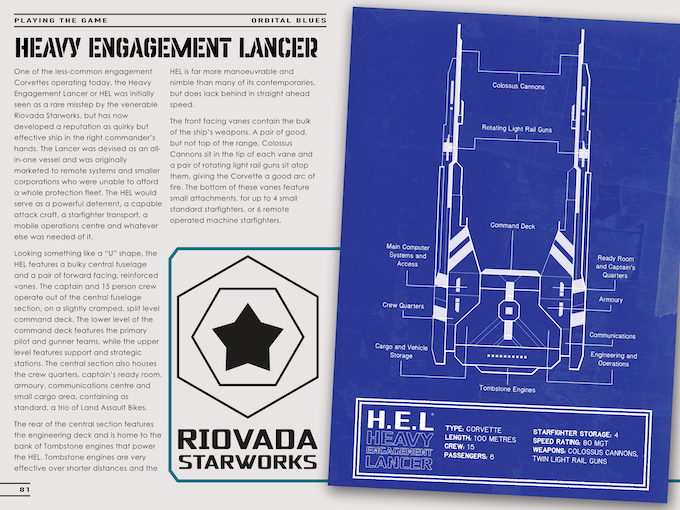

There’s three big components of Afterburn. The first is a real focus on spaceships and spaceship content. People always say, talking about those things, that the ship is the main character. You think about Serenity or the Millennium Falcon or indeed the Bebop as a character in that story. The Rocinante from “The Expanse” is another great example.

Every Orbital Blues campaign we spoke to was like, “Yeah, we named our game after the ship.” That’s the thing for all those media as well. The Bebop, Firefly, both named after the spaceship. We wanted to give people more tools and more ability to make those spaceships and come up with personalities for them. It’s kind of like a character creation book for the fifth member of your party with four people in it.

The other thing we added was this enormous adventure we’ve been working on that was spaceship themed. We wanted to focus emotionally on what the spaceship means as a part of the game, because in this game, your characters are literally leveling up by being sad. The level of ritual is called your Trouble Brewing. Trouble is this thing which generates XP for you by defining the way that your character has the Blues, and then you have this explosive unhealthy reaction at the end, and it tinges the game with sadness and anger and regret because it’s what’s possible from the mechanics that we’ve presented you with, the levers you can pull as a character. Ultimately, if your character isn’t wandering around, brooding, bleeding out trauma, they’re never going to grow as a person or get rid of it.

What we wanted to focus on in Afterburn is what the ship is in this metaphor. The ship is freedom, the ship is excitement, the ship is the love of the crew together, and it’s the reason why you don’t have a real job on a planet where you can’t make rent.

I talked earlier about the Blades in the Dark. My favorite bit from it is that you have a crew sheet for the gang. Here, we wanted to give you some options that made it feel like there was a character sheet for the spaceship. Just in terms of vibes, giving you a place to interact with each other, knowing how the thing looks and feels. That was super important to us.

It’s a very good chance to get the core team together again because Sam and Josh and I have been kind of off doing different things. I’ve been project managing and Sam and I haven’t really done any writing and Josh has been making literally hundreds of art pieces across all these different books. The art for Orbital Blues – you won’t believe it until you see it. It’s all like photo bashed, public domain art painted over to look like in-universe advertising materials and band posters and, like, postcards from some distant planet with two moons on it. Very truly, this is a pleasure to get the team back together again and keep making more books.

A big theme of Orbital Blues is pretty clearly about living under capitalism and then in Inevitable, you also talked about living in the world as it is today. How much does your perspective or your politics affect the games you write?

I’m a queer neurodiverse leftist who really hates capitalism and through my art, I have managed to successfully hack capitalism in a way that allows me to give money to artists, including myself, which is helpful. The stuff I make is all about those things. Best Left Buried is a horror dungeon crawler about working for a bank who makes you dig through colonialist ruins to make money for them, but in a way that destroys your character’s physical and mental health as they have to deal with these horrible dungeon monsters. That’s like a metaphor for us in a dangerous workplace with bad physical and mental health conditions to benefit someone in a suit somewhere to make money.

Orbital Blues is the same kind of story but it’s about self-employment. It’s about the gig economy. The hustle, making ends meet. It’s about, ultimately, people in terrible situations dealing with the things that happened to them in a really bad way.

Gangs of Titan City, which was mostly written by my friend Nick but I kind of helped guide through, is about desperate people in a gang in a not-Warhammer 40k universe influenced by Judge Dredd and Necromunda and Cyberpunk and stuff like that. It’s about people resorting to crime to break out of cycles. And then Inevitable is about dealing with the fact that civilization is doomed and the only thing that you can do on paper is work out how you’re going to be remembered.

Then this new game I’m writing, Paint the Town Red, is about being dead inside and being a vampire and that sucks, right? You’re kind of a creature that is inhuman, slowly passing through time, watching everyone you know die around you, desperately trying to find out ways to love.

It became evident to me a couple years ago that all of the stuff I was writing was about people struggling to escape structures made by society. When I realized that, it really changed the way I started making games. The first couple times it was an accident. I wrote Best Left Buried, Sam and I wrote Orbital Blues together, and I found at the end that I’d written something quite meaningful about workers’ rights and the status of people in society. I don’t know if Sam would say the same thing, but certainly to me, it was like, “Oh, this game, it’s not about being a cowboy, it’s not about dungeon crawling. It’s about what I believe about the world.” The fact that there’s a through line about that, through everything I’ve made, and everything I probably ever will make is quite significant.

If you’re in Turn Order’s VtR game, skip this next question! We’re telling secrets!

Well, speaking of capitalism, I have to go to my job in a few minutes, but I want to make sure we talk about Vampire. I’ve been watching you play directly so I’m getting an idea of who you are as a player. Do you like these intense political and high-stress situations in your games? Does that inspire the games you write?

Yes, so the Vampire game has been really interesting because it’s not the kind of game I’d normally play. It’s very trad, which is like the opposite to the indie stuff I write, if you have indie story games versus a traditional story game, if you kind of listen to the dichotomy there. I very much made my character, Morgan Shawbrook, with a specialty design.

He was a master of Elysium in the 15th century and beforehand and then he’s come out of a very long torpor. He was an important nobleman and I was kind of looking to play on a sort of “fish out of water” gimmick because I don’t know anything about Vampire: the Requiem lore.

Morgan went to sleep in 1772, I think was the year, which was the year the pub that I envisaged him running, the Prospect of Whitby, sort of fell out of favor and a different pub was the Elysium in London.

What ended up happening is my character has ended up with a completely different job, doing a completely different thing. I wasn’t expecting all this stuff to happen. My character somehow ended up as the Master of Stewards of the city, but his actual job is that he’s been appointed by the prince to root the Strix out of London and conduct a shadow war against all of these potential demons, which is something that as a character, I’m just not equipped to do. All of my points are in social engineering, and I tried to punch someone earlier today and ended up rolling with minus one dice. I’ve been set up as the commander of a desperate war with no ability to fight. What I’m enjoying about it is the sort of fish out of water experience of playing a character who is laser focused on a particular thing, really trying to do as best he can in a really difficult situation.

I think this is definitely the most political high stakes game I’ve been involved in as a player and mainly GM, to be honest, so it’s a thrill to actually play this kind of game. But I’ve loved playing VTR and it’s been the most fun I’ve had playing an RPG in months, if not years. Lupe and you built such a magnificent world for us to interact with. All the players that I’ve started engaging in my foibles and schemes as a sort of puppet master have bought everything I’ve done hook, line and sinker so far, I think.

That’s great. Is it giving you ideas for your own vampire game or is it too completely different?

It’s made me really think about the era of games this was made in. I’m understanding that the people who play Vampire passionately are very different people to my normal customers. It’s kind of helped me plot out the core mechanics and try to work out how to get some of the stuff that Vampire is really good at, particularly surrounding humanity, vitality, willpower and touchstones, that I can sort of build into a system with less than six numbers on it, including all the stats. It’s been a fascinating way to take something as a direct reference point and work out how I could engineer a similar experience but having a very different emotional pull. In the in White Wolf games, the characters are very explicitly just unforgivably terrible people and the magic that they possess makes them monstrous in a quite meaningful way.

It still sucks to be a vampire, don’t get me wrong: death is a curse and the fact that you have to prey on people to live is horrible as a player. But, I wanted the vampires in my game to be objects of pity rather than hatred, because it should really suck to be a vampire, but for a different reason. Navigating that plane of existence is always really difficult. I’m definitely going to be taking bits away from this vampire game and making it my own.

Thanks again to Zach for being my first interviewee for Turn Order! I truly would’ve been happy to talk for another hour.

I’d love to do more content like this, so if there’s a game creator out there you’d like to see featured, drop me a comment or message my Twitter @luke_taylor23 and I’ll see what I can do!