In our Start Competing series, we look at the basics of competitive play for different games, and talk about how to take your game to the next level. Today we’re talking about how to start playing at tournaments, and the practice you can do to prepare yourself for small events.

This article is intended for players who want to make the jump to playing in events, or have played in one or two and want to start competing seriously at future small events. The aim here is to take you from casual four-hour games on Saturday afternoons to tight play at events that can see you going home 3-0. If you’re already a regular player at small events and are looking for ways to step your game up and compete at larger events, then I recommend checking out next week’s article on how to get the most out of your practice games and build a regimen that will take you from the RTT circuit to competing at the top levels.

Today, we’re talking about making the jump from casual to competitive play. And the first thing you have to know is that there’s no substitute for practice.

You Have to Play More Games

Every summer, my group of friends – which includes fellow Goonhammer author and my forever bro Greg – all get together and we rent a house somewhere for a week. It’s usually near the beach or a major body of water (Phil likes to go kayaking) but sometimes in the mountains. We (usually there’s around a dozen of us but as many as 20 people can show up, though some people only stop by for a day or two) then spend the week hanging out, cooking big community meals, drinking, playing games, watching movies, and staying up late talking about important nonsense and making each other laugh, fighting sleep for as long as we can in the hopes that doing so will somehow make the week longer. In the summer of 2019 (last year as I write this), we picked a place in the Pocono mountains up in northern PA. With only a month or so between this week-long vacation and the NOVA 40k GT, Greg and I decided to bring our armies with us so we could get in some practice games. We were both registered for the GT and while I knew what to expect from attending in 2018, for Greg it would be his first ever tournament experience for 40k and while he didn’t expect to win, he also didn’t want to lose every game. So we sat down four times that week to play practice games with our armies.

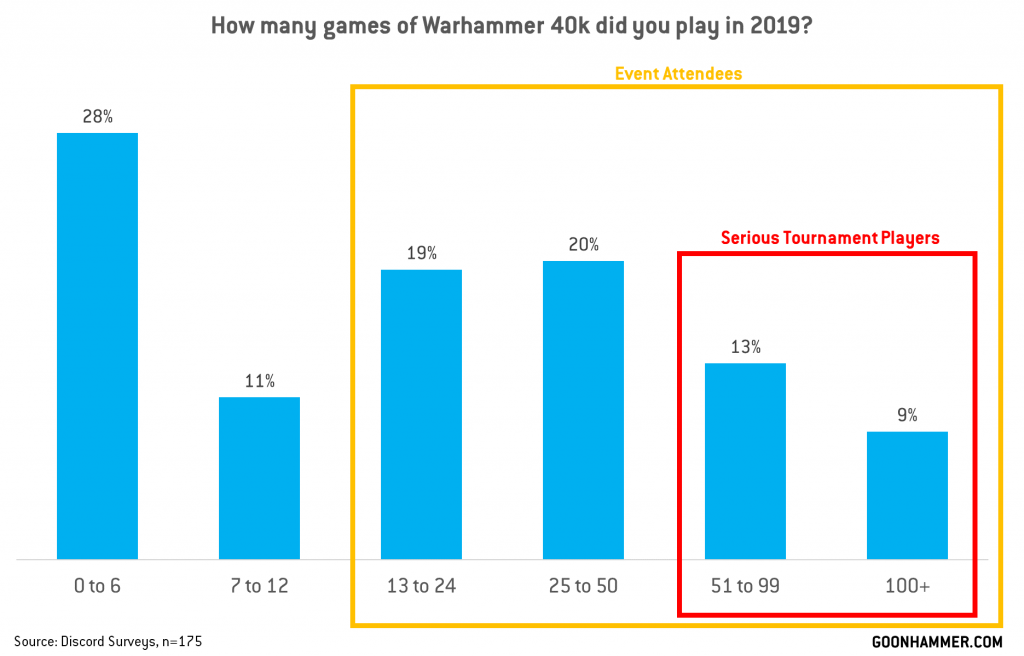

Getting in more games is probably the hardest part of making the jump to regular competitive play. Based on my conversations with players in this space and some casual polls we’ve run, most casual players are topping out at 24 games per year (about two per month), and most of those players get in less than one game per month. At the most casual level, these are really informal affairs with pizza and beer, where it’s not uncommon for a 2,000-point game to take an entire afternoon and run from noon to 6pm when you factor in set-up and breaks for food or whatever else. Most of my games against Greg up to this point had been games of this type, where I’d show up at his house on a Saturday afternoon and we’d get in a game, sometimes doing doubles with friends or a 2v1 with SD47, and then switch from 40k to dinner and drinking later in the evening. Doing this every weekend or on weekdays is a really big ask for a lot of folks, even those who just want to go to the occasional tournament.

Playing one or two games per month isn’t enough. It’s not really enough to learn your army’s rules and stay on top of changes in the game, and it’s not going to be enough to get familiar with the specific list you’ve built, let alone optimize that list. If you want to get better, maybe even have a real chance at winning small events (or doing OK at larger ones), you’ve got to play more games. There are specifically three things you need to do that playing more games will help you with:

- You have to know the game rules

- You have to know your army’s rules

- You have to know how your army plays

The only way to do this is to play games, learning the rules via repetition and experiencing how the army plays. You’ll play better – you will be less likely to forget to use key rules and Stratagems. And one huge benefit of knowing the rules and how your army plays is that you’ll be able to play faster. Which is good because…

You Have to Play Faster

For each of the games Greg and I played that week, our goal was to get through the game in under two hours. We didn’t have a chess clock, so the key here was just to play faster – reduce downtime, make decisions quickly, reduce the amount of time spent looking up rules. We used the same armies in each game, and went as quickly as we could while still playing mindfully, speeding things up each time (it also helped that the first couple of games were “over” after a few turns).

Tournament play is significantly different. It’s not bad or less fun, but it’s much tighter and games go much more quickly. If you want to have a good time and win some games, you need to familiarize yourself with this kind of play. The easiest way to speed up your game is to know the rules of the game and for your army – not having to look up rules during the game saves a ton of time. You don’t even have to remember everything – you are free to print out reference materials like datasheets from buttscribe or have datacards on hand. Practice games will also help you do this – knowing how your army works, what your general game plan is, and how you can accomplish specific secondaries will help you reduce the amount of time you have to spend thinking about what you want to do and free you up to think more about what your opponent is doing and how you want to respond, and streamline the whole process. There are also little tricks you can learn to speed up things like dice rolling, keeping dice on hand and building quick pools as your opponent rolls hits/wounds against your units.

Liam: Two things that I do that I think are pretty common to most experienced players but often seem elusive for others are 1) have dice pools be a natural part of your gaming kit, e.g. I have a whole bunch of dice in different colours in fixed sets of 12s, which makes it really easy to grab the right amount instead of having 50 identical dice to count out and 2) plan your turn in your opponent’s turn. Point 2 is especially important – you have a lengthy period each battle round where you are not the active player, so use that time to consider what you’re going to do. This sounds obvious, but I have played plenty of games where it’s evident my opponent has not even begun to think about their moves until the start of their Command phase, robbing themselves of lots of valuable planning time, especially if they’re on a clock.

Many events use chess clocks to time players. I find playing with a chess clock to be incredibly stressful, and if you haven’t played with one, you should consider grabbing one and practicing with it. Playing with a chess clock requires adding an additional, crucially important element to the experience – you need to remember to continually stop the clock and if necessary, remind your opponent to stop it as well so you aren’t using time that’s theirs. It’s easy to forget the clock if you aren’t used to playing with one and find yourself suddenly looking at 3 minutes of time left for 3 turns of game. This is something you can easily prepare for though – get a chess clock or use the stopwatch app on your phone and practice starting and stopping time when you have priority or its your turn.

Here’s the thing: Even if you have no plans to play in tournaments, this is still a really good thing to do. Maybe you don’t have to practice with chess clocks, but speeding up your play will make your casual games more fun too. They’ll be smoother, feel like less of a slog, and you may even get to play an extra game if you finish early. The reason players like JONK are able to hammer out 100+ games in a year isn’t because they have no home or social lives; it’s because games don’t take them 4+ hours to play (in fact, most of JONK’s practice games take an hour and don’t finish, but we’ll talk more about that next week).

Learn How to Play With Your List

Greg and I used the same lists in our games that week, but part of that was that we didn’t bring extra models. We both had plans to tweak the lists before the event based on our play (well, Greg didn’t but I bought him another Darktalon and he was kind of forced to improve his list. Eat shit, Greg). And that meant that the armies we were playing with had changed. Greg added the Ravenwing Specialist Detachment and I swapped out a portion of my army for Daemons in order to add a Bloodletter bomb. These were significant changes that would require different pregame planning processes and new stratagems. In the three weeks between the end of the vacation and NOVA, I got in two more practice games against friends running more serious lists – my buddy Kingsl4yer running Space Wolves and my friend Brandon running a version of Jim Vesal’s daemons list, while Greg got in a pair of practice games on his end. The night before NOVA we played a final practice game just to get in one more rep. This was on the whole a pretty good effort but it wasn’t nearly enough. Still, it was a massive help and meant at least that going into the games I knew all of the rules for my army.

In addition to knowing your rules, you have to know your list. Simply put, you will have more success playing a bad list that you are intimately familiar with than a good list that you have never played. And this is true at all levels – Nick Nanavati famously ate shit at LVO 2020 when he switched to White Scars the week of the event. It was likely a smart decision for the Broviathan list meta and the terrain layouts at the time, but he didn’t have time to get in more than a couple of practice games with the army and ultimately dropped early after a pair of losses. It’s a classic case of making last-minute adjustments with the right intentions not paying off.

Liam: This part is incredibly important. A really common misconception from players on the fringes of competitive play is that the best way to win is by picking the right list, and then all the hard work is done for you. Players familiar with That Guy in their local stores will recognize the cycle of ‘a list wins a big event, he immediately buys and hastily assembles its components, and then has indifferent results with it before throwing it away for the next meta list.’ That Guy never really learns how the list works or its capabilities, and if he does win games it’s usually because he’s playing lower-skill players who aren’t equipped to deal with the raw power that a top list usually represents. Very good players can change armies reasonably fluidly, but if you’re the person this article is for, playing your 1.5 games a month and attending an RTT once a year, that ability to switch seamlessly between significantly different lists or factions is probably not within your gift.

Learning From Your Mistakes

As we played the games, Greg and I would talk through certain decisions. After each game, we talked about the game – what we did, what we could have done, what didn’t go well. We talked about what was working with the list, and whether it needed changes, and how the lists’ strategies might change against different opponents. This is also where we’d talk about making minor tweaks to the list and how they might play, and talked about how the armies might execute against different threats.

I don’t want to focus too much on this part right now – it’s important to learn from your mistakes and structure your practice in order to learn – but at this point, your primary focus should be building familiarity with the rules, your army, and your list. You don’t have to learn the meta or know what every other army can do (though knowing some of the key tricks doesn’t hurt) to do well at a local event, but you do need to be able to finish games and execute your army’s plan.

Liam: I would disagree here only in that I think the two things are inseparable. Finding out where you have a knowledge gap – you forgot the rules or didn’t know them in the first place – isn’t fundamentally different to learning where you have a skill gap – you knew the rules but used them badly. One really common habit I see from poor players who don’t ever improve is that they never pay attention to either thing. If they do acknowledge mistakes it’s often in the form of “I just did this one thing wrong” and focusing too much on that individual thing instead of the broader game, or even more commonly blaming ‘dice’ and pointing to a singular moment where the dice let them down as evidence. The truth is that the majority of the times that ‘dice’ lose you the game it’s because your plan was bad, often because it was over-optimistic and relied on too many things performing above average, because it relied on a faulty understanding of the rules – or because there wasn’t much of a plan in the first place. Anyone experienced will remember having a game against an opponent who looked like a tough prospect with a good list on paper, only to watch them flail around with it and fail to prioritise targets well or focus on scoring points. If this is you – let’s say you routinely find yourself at the end of the game with your forces destroyed and your opponent’s not, or even if you do generally do ok at killing their units but they are unaccountably 40 points ahead on the mission – then the best thing you can do for yourself is to honestly look at your game and think about things like “why did I fall behind on primary?” or “which secondaries did I score poorly on and what could I have picked that I would have done better on?” or “what key unit really ruined my day and how could I have done more to deal with it?”

Putting It All Together (and Probably Still Losing)

It’s difficult to imagine having a worse start to NOVA than the one I had in 2019. After all that preparation and prep I ended up eating complete shit in my first game against Robbie Triplett, watching my Kytan explode and take out more than half of my army. But things steadily improved after that, and the prep I put in helped me relax a bit more during my games, turning what could have been a stressful event into something much more laid back, especially after my first loss put me in a situation where there was nowhere to go but up.

Even with prep, you’re likely to lose some games, especially early on. But putting in some basic practice will help ensure that you actually enjoy your tournament experience, and that you have the ability to focus on the games you’re playing and how to respond, rather than just trying to execute a full game of Warhammer 40k in two hours. And that’s the first step.

Now if you actually want to start winning some games and events and taking on bigger events like GTs and majors well, we’ll talk about that next week when Jon Kilcullen talks about taking your game to the next level and practicing in a way that helps you accomplish that. Until then, if you have any questions or feedback, drop us a note in the comments below or email us at contact@goonhammer.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.